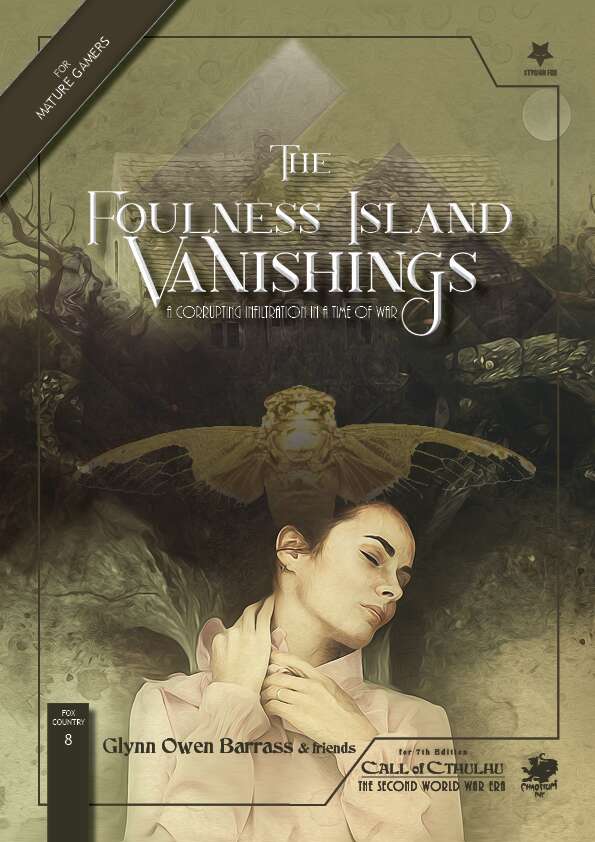

A review of The Foulness Island Vanishings, by Glynn Owen Barrass & Friends

Stygian Fox is producing original Call of Cthulhu 7th edn. scenarios at a rate of knots nowadays, and this Second World War Era volume by the illustrious (and industrious) Glynn Owen Barrass is a shining example. The Foulness Island Vanishings: A Corrupting Infiltration In A Time Of War, in full, is, unsuprisingly, set on the real-life Foulness Island off the south-eastern coast of England in 1941, and mingles wartime paranoia with far more malign influences. The whole scenario breathes a very strong sense of time and place, like something out of a Second World War propaganda film – perhaps Went the Day Well? with its bizarre breakdown of English village life – and contains a lot of useful setting information that could be applied elsewhere. And although the scenario is fully written out for CoC 7th edn., it doesn’t look hard to tweak for Achtung! Cthulhu or other appropriate systems.

As for the scenario itself, its 84 excellently illustrated colour pages make full use of the island’s diverse locations and inhabitants in unveiling the story of a very strange infestation indeed. The maps, handouts, and house plans match the high visual quality of the rest of the book. The horror tropes are at times pretty unpleasant, and the scenario carries a Mature Gamers rating for a reason. There is certainly plenty of human evil on display, redolent of wartime atrocities, but the Unnatural brings in its own level of veriest awfulness to boot. By the end, Investigators certainly won’t feel that they’ve had a drab wartime ration of adventure and horror.

If Stygian Fox continues its present tear of high-quality Cthulhu Mythos material, I think we’ll all be the better for it. Production values are superb, and easily match the quality of the core 7th edition materials. And Stygian Fox’s choice of subjects seems to be sweeping an attractively wide field. For now, take a mental time-out from sequestration to enjoy another time and place of isolation and menace, and experience the foulness of Foulness.

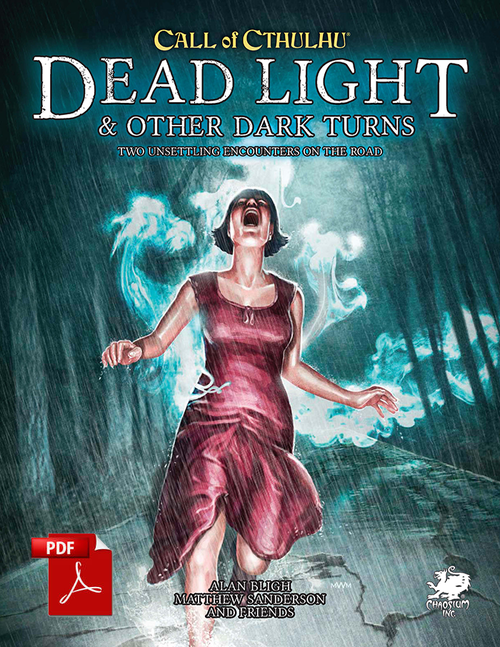

A review of Dead Light and Other Dark Turns, by Alan Bligh, Matt Sanderson, Lynne Hardy and Mike Mason

If you’re driving in backwoods America, don’t stop for anything. That’s the lesson of Dead Light and Other Dark Turns, Chaosium’s latest scenario book for the Call of Cthulhu 7th edition rules. Alan Bligh and Mike Mason’s Dead Light should already be familiar to many of Call of Cthulhu aficionados as it was first published in 2014. The original edition appeared in dual-statted form to allow players to have a taste of the new 7th edition rules in progress. This new version fine-tunes and fully reskins the scenario for 7th edition, while also updating the materials to the current Chaosium style and level of quality with brand new artwork. It also includes a brand new scenario in the shape of Matthew Sanderson’s Saturnine Chalice. The old edition was just 32 pages: the new one is 90 pages, including extensive handouts. The scenarios are written for classic era 1920s CoC, and unfold in typical Lovecraft country, but could be rejigged for other periods and locations with relatively little effort.

Back at its first release, Dead Light was hailed by at least one reviewer as: “the best title released by Chaosium in years.” Since then, Chaosium has arguably upped its game and has been churning out high quality work in spades, but Dead Light especially has an original and unusual nemesis whose characteristics help add a nasty tinge of moral squalor to the cosmic horror. Saturnine Chalice may seem a little more familiar in its choice of threats, at least on the surface, but the clue trail is (optionally) puzzle-based, which makes for a different slant on typical gameplay, and the unfolding mystery is rich in head-fuckery. There are also shorter seeds for road trip encounters and adventures at the end of the book.

This is definitely a worthwhile addition to the roster of 7th edition CoC scenarios available, especially for shorter more stand-alone adventures. At the inconsequential price that Chaosium is asking for it, it’s a steal even for owners of the original Dead Light. Recommended for Call of Cthulhu players old and new.

[Top]A review of New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, 2nd edition, by Tom Lynch, Christopher Smith Adair, Oscar Rios, Kevin Ross, Keith “Doc” Herber and Seth Skorkowsky

As the blurb for Stygian Fox’s Kickstarter explains, “Miskatonic River Press released New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley to great acclaim and it quickly became a favourite among Call of Cthulhu Keepers.” This is essentially a resurrection of a much-loved scenario book, originally published in 2009 as a follow-up to Chaosium’s 1991 Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, which also gives an opportunity to see how RPG publishing has moved on since Chaosium’s 1991 effort and the original New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley. Tom Lynch’s personal dedication to the book is a heartfelt reminiscence of Keith Herber, CEO of Miskatonic River Press, lamenting the sad demise of the publisher and the publishing house. Keith Herber was a powerhouse of scenario-writing in the early days of Call of Cthulhu, producing almost 50 scenarios for Chaosium in the 1980s and early 1990s, and it’s not surprising that his tragically short re-emergence as founder of Miskatonic River Press in 2003 has left a lasting impression on the modern Lovecraftian gaming scene. The whole exercise obviously has had a lot of love lavished on it, and Call of Cthulhu players are the fortunate beneficiaries.

The original six scenarios in New Tales have stood the test of time and are reprinted in full, freshly rejacketed and statted up, not only to run on Call of Cthulhu 7th edition rules, but also to bring their presentation up to the kind of standard we’ve come to expect from the newly reborn Chaosium and their associated projects. There’s an additional new scenario from Seth Skorkowsky, “A Mother’s Love,” extending the book’s coverage to Innsmouth with an appropriately twisted tale of miscegenation and mayhem. I’d still be happy to play these scenarios through with earlier Call of Cthulhu rules, or indeed with Trail of Cthulhu or other systems, because they focus so much on drama and story rather than pure game mechanics. There are plenty of human protagonists and antagonists with their own mundane agendas that can trip up the players as effectively as any scheming cultists. The unnatural horrors that do appear are a refreshing mixture of new takes on Cthulhu Mythos staples and original creations, and should be enough to stimulate the most jaded Call of Cthulhu grognard.

The real surprise for anyone familiar with the black-and-white layout and fairly limited art of the original is the visual presentation of the 2nd edition. Stygian Fox has done a frankly incredible job on the production values. The maps of Arkham, Dunwich and other favourite Lovecraftian locales are the best I’ve seen, even when set against the superb cartography in the latest Chaosium products, and the handouts and period prop pieces are equally luscious. Stygian Fox was working off a Kickstarter that closed at roughly 400% of its target, and the money has been well spent. There are even terrific multi-page handouts for pre-rolled characters. “The original is black and white and 130 pages,” Stygian Fox noted. They managed to expand the final publication to 240 full-colour pages.

Would I recommend this book to anyone who had the original edition? In a heartbeat. It’s not just the extra material and the restatting of the stories to Call of Cthulhu 7th edition. It’s the superlative production, which is bound to be usable in other campaigns. Indeed, if you want to run a 1920s campaign in canonical Lovecraft Country, I’d advocate this book as a go-to for mapping out all the core locations – Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, Kingsport, and environs – in immaculate style. The full-colour double-page panorama of Arkham, for instance, captures that Mythos-ical city exactly as I’ve always imagined it. Furthermore, Chaosium still hasn’t released updated 7th editions of many of its own classic Lovecraft Country scenario books – such as Keith Herber’s original H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham and H.P. Lovecraft’s Dunwich. That puts New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, 2nd edition to the fore as the Number One CoC 7th edition canonical Lovecraft Country supplement – a position it full deserves to occupy. It’s a testament to the current health and vigour of Call of Cthulhu gaming, and a worthy tribute to its progenitor.

A review of Petals and Violins: Fifteen Unsettling Tales, by D.P. Watt

Introduction by Peter Holman, Afterword by Helen Marshall

D.P. Watt is already a Shirley Jackson Award nominee for his 2016 collection from Undertow Publications, almost insentient, almost divine, so he’s well established among readers of weird and dark fiction. In fact, he’s written 8 books by my count, including this one. Despite the fact that Petals and Violins comes heavily flagged as a chunk of the Weird Renaissance, with an afterword by Helen Marshall, there are plenty of stories here that would appeal to the most recherché traditional ghost story enthusiast. D.P. Watt is not especially a representative of any particular school or trend, and very much his own animal. The author has said in one past interview that “The process of composition changes with each story, and I have no particular allegiance to any movement, nor indeed anything as well-formed as a technique that I can deploy. My writing seems now to be more driven by scenes that emerge as I am working.” (Bibliophagus, 2015) That’s certainly what comes across here, and it’s a process that’s to be welcomed.

The opening story, “Blood and Smoke, Vinegar and Ashes,” for instance, is a tale of folk alchemy in rural Poland, and the remarkable results achievable by the quoted ingredients and others; M.R. James could have well produced his own version of the theme. “Mizpah” and “The Magician, or, Crab Lines” also have that flavour of folk horror, in narratives closer to Daphne du Maurier’s The House on the Strand. (Indeed, du Maurier’s blend of psychological tension, the paranormal and supernatural, and a very strong English sense of place and the past, finds substantial echoes in D.P. Watts’s work.) The most ambitious, and distinctive, story in the book is “Conflagration: Immoral Vignettes,” a slideshow of historical, tragical tableaux featuring writers from 1895 to the present, from August Strindberg to Tadeusz Kantor. D.P. Watt has certainly experimented plenty with form in the past, notably in his novella The Ten Dictates of Alfred Tesseller, and this is the most stylistically extreme story in the collection – and, in my opinion, one of the best. I could go on and on about the value of using history and aesthetics as imaginative resources, instead of typical horror set-dressing or weird psychobabble, but it definitely works. Any more traditional reader who balks at this approach is advised to stick with it. “The Pedagogue, or, They Muttered” is more in the Lovecraftian vein of pedantic academia touching cosmic horror, while “A Species of the Dead” is closer to psychological horror, where the disturbance of the natural order is purely social and mental.

It goes without saying that a writer this experienced is fully on top of his craft, and can turn a phrase or string a narrative with hooks. Weird or dark fiction, ghost stories, horror or surrealism, whatever you call it, this loose cluster of genres is in rude good health in Britain right now, and D.P. Watt is a tremendously accomplished practitioner. Petals and Violins is a box of dark gems.

A review of The Boughs Withered (When I Told Them My Dreams), by Maura McHugh

Irish short story and comic book writer and critic Maura McHugh has appeared in so many venues, including horror and weird fiction bastion Black Static and prestige anthologies like Joe S. Pulver’s Cassilda’s Song, that it comes as something of a surprise to learn that this is her first story collection. But so it is, spanning some 15 years of work, with 20 dark and weird tales, 4 of them original to this volume. With a title cheekily adapted from a verse of W.B. Yeats, a cover design by the ever-inspiring Daniele Serra, and the usual high production values of NewCon Press, The Boughs Withered (When I Told Them My Dreams) is an attractive enough package on the outside. What’s it like on the inside?

I’m glad to be able to report that The Boughs Withered is refreshingly diverse, varied in tone, diction, setting and even genre niche, and more imaginatively rich and highly coloured than many contemporary debut weird and dark fiction collections. There’s a snap to the dialogue and an engaging narrative pulse best captured in stories like “Spooky Girl” and “The Gift of the Sea.” It’s typical of Maura McHugh’s writing that the latter story manages to marry modern post-GFC Ireland with the spirit of Celtic mythology seamlessly. I don’t know if this is some kind of Flann O’Brien Irish gift to speak in many tongues, but it certainly makes for some highly enjoyable reading. The author commands a whole gamut of styles, and hardly ever leaves you feeling that her wordplay is wasted or overwrought. The settings also range from the Russia of legend to modern New York, with Ireland taking a leading but by no means an exclusive role, and some of that ranging afield has clearly been pivotal to her development as a writer, as she explains in her Afterword. She may write to “intuit the overlooked people who have been silenced,” but this is by no means her only concern. One of her most Irish historical stories, “Home,” is also one where cosmic horror slips into the picture, as it does in “The Diet.” Then again, at least one other story, “The Hanging Tree,” is “almost not supernatural at all” – but still very unsettling.

I don’t know what kind of expectations you might come to this book with, but chances are you’ll find them transcended. There’s infinite enough variety in it to upset anyone’s preconceptions. You’ll be spooked, but you’ll also be thoroughly entertained. That’s a far more important thing than is sometimes realized, and far rarer too. Maura McHugh brings it off in style. The Boughs Withered is a book you’re likely to come back to again and again just for the sheer pleasure of reading it. Now how uncommon, and how important, is that?

[Top]A review of The Ballet of Dr Caligari and Madder Mysteries, by Reggie Oliver

Reggie Oliver has become an institution in modern British horror, producing volume after volume of finely crafted stories in the best tradition of weird fiction and ghost stories. Thanks to him, any reader who enjoys tales of this kind has a hugely enlarged bill of fare to sample – this is his eighth collection, containing thirteen stories. It’s produced to the usual superlative standard of Tartarus Press collectible editions, although for anyone who can’t afford the very high, but completely justified, hardback price, there are equally high-quality ebook copies in various formats available from Tartarus, as well as paperback. So how mad, and how mysterious, is it?

A couple of the stories here are straight recreations or completions of the work of M.R. James. “ The Game of Bear ” completes an unfinished story by James in exactly the kind of manner a Jamesian fan could expect, with a suitably ghastly conclusion. “The Devil’s Funeral” is a historical ghost story in the epistolary style mastered by James, concerning an appropriately folklorish local tradition and a haunted clergyman. If you come to Reggie Oliver’s work looking for such pleasures, you’ll find them in plenty. Jamesian antiquarian ghost stories are only part of his range, though. There are other stories here with a strong antiquarian and historical dimension – “A Donkey at the Mysteries,” “The Endless Corridor,” “The Vampyre Trap,” “Lady with a Rose” – but they are mostly either framed in a much more contemporary context, or have a very different take on the narrative. “The Vampyre Trap,” for example, is more of a historical detective mystery than a ghost story, though with a strong gothic dimension. And the historical and scholarly trappings are often more in the spirit of that other great British master of the weird tale, Robert Aickman, with all the appropriately surreal and psychologically ambiguous flavour. “The Ballet of Dr Caligari” itself, with its disturbing evocation of a demonically influential stage piece, or “The Final Stage,” a nightmare dream journey through fragments of identity in masks and mirrors, smack of quintessential Aickman. Reggie Oliver is far beyond just a follower of the Jamesian tradition. He does have many styles and registers, from the genially satirical to the historical pastiche, but of all the dark and weird tales I’ve read, at least one of his stories sticks in my mind as one of the few that has genuinely scared and disturbed me, and in this jaded age, that’s saying something.

The classic English ghost story, then is very much alive in Reggie Oliver’s hands. It’s also far beyond what it appears to be on the surface, even if those surface aspects will be the chief attraction for many readers. A supremely enjoyable volume, from a writer who seems to go from strength to strength.

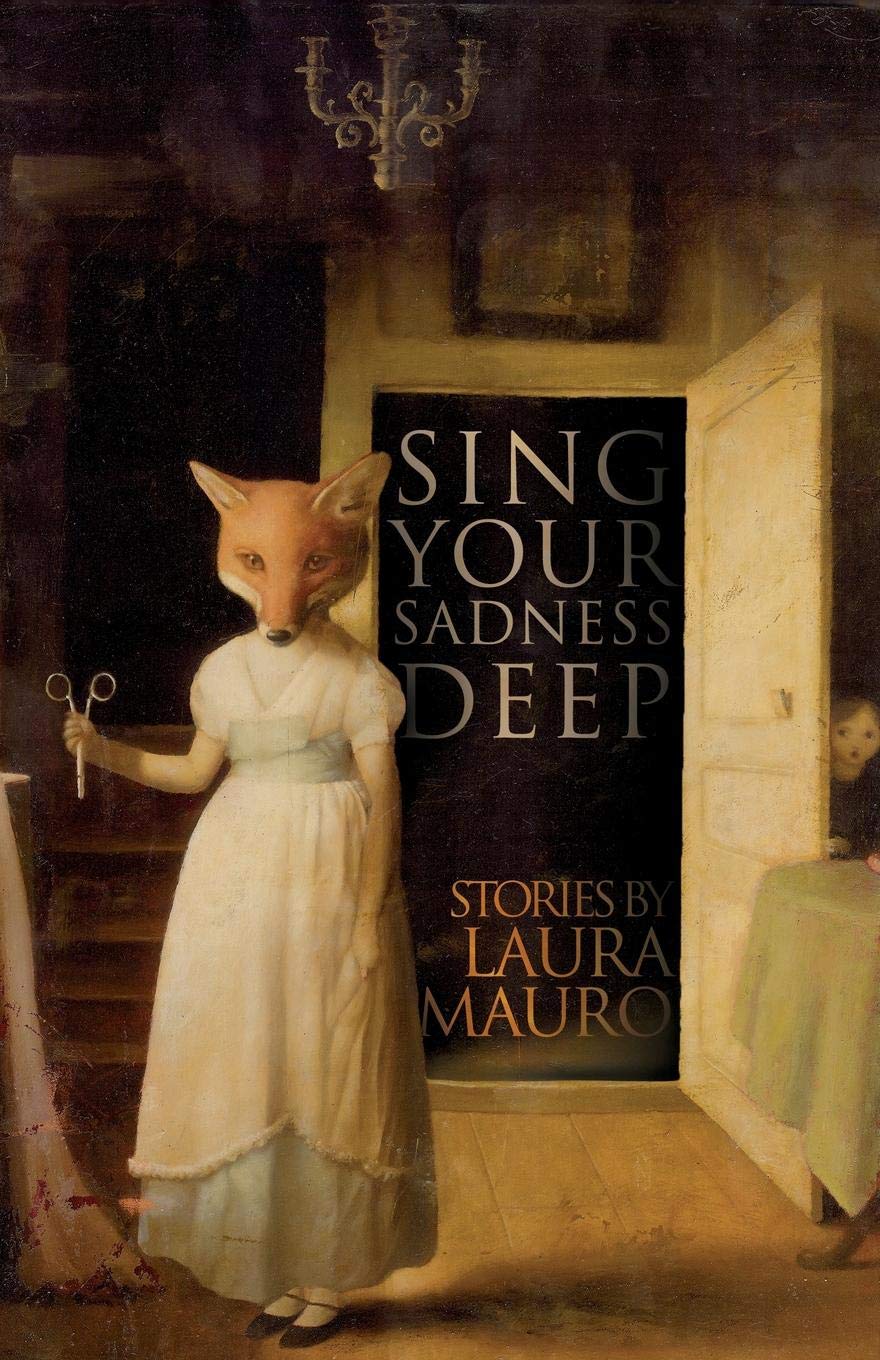

[Top]A review of Sing Your Sadness Deep, by Laura Mauro

Laura Mauro’s first collection delivers on the promise that has netted her a British Fantasy Award and a Shirley Jackson Award finalist placing, and its quality is so consistently high that I’m sure more awards must be on the way. The thirteen stories herein are at least that good, spanning her career from her first appearance in Undertow Publications’ Shadows & Tall Trees 4 in 2012 to date, in a book produced to Undertow’s usual superlative standards.

There’s an awful lot of toxic family dysfunction in this collection. Philip Larkin fans will be very glad to have “They fuck you up, your mum and dad” confirmed in spades. Not just mum and dad, but epileptic sister, bizarre homesquatting homunculus, birdboned acephalic foetus, foggy revenant father, guilty bloodstained mother, fish-skinned foundling, wooden changeling sibling, angelic adoptee, painsucking grandpa. Look at the cover illustration, so well suited to the contents, with the girl-child peering from behind the door at the fox-faced (mother?) figure in Jane Austen dress, scissors threateningly poised. That’s how distorted, surreal and mutagenic relations and relationships are in these tales. Almost always here the strangeness blossoms from the cracks and fault lines between people.

As that might suggest, the story premises here are resolutely weird, and very seldom what you’d expect. There’s a welcome diversity of setting and background, as well as of inspiration and narrative trope. Laura Mauro is a British weird fiction writer, but she doesn’t let that constrain her in the slightest. Story settings range far and wide, from suburbia to Siberia, Utah to Oulu, Brighton to Bothnia, the Isle of Wight to Ireland, Sussex to Sicily – all rendered in a spare, sinuous prose that weaves its way through the intricacies of the stories without pausing for self-indulgent ornamentation. I would be very interested to see where she goes from here, but I’m confident that it will be broader and even better – as far as that’s possible. British weird fiction is fertile indeed if it’s producing first growths like this bouquet of porcelain flowers of pain. Highly recommended.

[Top]A review of The Very Best of Caitlín R. Kiernan

With a writer like Caitlín R. Kiernan, a title like The Very Best of… is begging a lot. Where’s the ferociously parodic, deconstructive urban fantasy she writes under her Kathleen Tierney nom de guerre? Where’s the Delta Green-flavoured Lovecraftian technothrillers like Agents of Dreamland and Black Helicopters? Where’s her comic contribution to the Sandman mythos? In any collection from such an author, there’s always bound to be, not only favourite stories, but entire sub-genres missed out. I want to put in this quote to illustrate the point, because it’s the kind of thing you so rarely get to include in a review: “Brown University’s John Hay Library has established the Caitlín R. Kiernan Papers, spanning her full career thus far and including juvenilia, consisting of twenty-three linear feet of manuscript materials, including correspondence, journals, manuscripts, and publications, circa 1970-2017, in print, electronic, and web-based formats.” Count ‘em: twenty-three linear feet. It’s a brave editor or publisher who would dare try to encapsulate every facet of an author so various, and so prolific.

What this compilation does demonstrate is that Caitlín R. Kiernan is producing the very best of contemporary dark and weird fiction, regardless of whether or not that typifies her whole range. She not only has written more than nine-tenths of her contemporaries, she has also written substantially better than nine-tenths of them. She casually throws off metaphor and imagery in passing that would make any other writer’s career. Kiernan has a word horde as rich as Smaug’s, and a voice as mesmeric.

Part of her mastery of different genres and sub-genres is her unerring ear for the idioms, idiolects, speech communities, buzzwords, shibboleths, jargon, psychobabble, technobabble, Mythobabble of each side alley and cul-de-sac of imaginative literature. Her debt to 1890s decadent literature might have helped tune her ear for distinct prosodies, but even when it’s fully on view, as in “La Peau Verte,” it isn’t anything like as overblown and cloying as Angela Carter or Poppy Z. Brite. Kiernan’s frame of stylistic reference isn’t anything like that narrow, and she doesn’t wallow in overwrought prose like many self-declared decadent authors. She tosses in quotations and references from the whole gamut of literature that you’d ache to see more often in genre fiction, yet she keeps a sinew and thrust in her writing that nails all the glitter and sparkle of her stylistic brilliance firmly to the underlying contours of her narrative. Sometimes her more experimental pieces do tax the reader’s patience – I’m no fan of the unparagraphed construction of “Interstate Love Song (Murder Ballad No. 8)” for instance – but such excesses are rare, and generally tempered by a propulsive impetus, let alone a turn of phrase, that makes her fables unputdownable. “Houses under the Sea,” does dip into the deep waters of her best-known single work, The Drowning Girl: A Memoir, but that doesn’t render this collection any less a partial glimpse at best. And there’s that word again.

Kiernan has gone on record in the past to state that she’s “getting tired of telling people that I’m not a ‘horror’ writer. I’m getting tired of them not listening, or not believing.” It’s true that miscegenation and body horror are recurrent themes – steampunk prostheses, flesh sculptures, alien distortion/transcendence of normal humanity – frequently embodied in or espoused by mutated former lovers. Yet she typifies horror as “an emotion, and no one emotion will ever characterize my fiction.” She’s also said that “story bores me. Which is why critics complain it’s the weakest aspect of my work.” I don’t see any lack of story in these stories, though. I also suspect that Kiernan wouldn’t have been able to keep readers’ attention across such a huge volume of work unless she was able to keep them engaged through extended narratives with more than just jewelled individual sentences. She shares that characteristic gift of a really good short story writer of tieing off a section or a passage with a line that hooks you and leaves you gasping, aching to see what comes next. And if she has any uniformity of tonal range or register, it’s one that carries superbly well across genre after genre, from the folk horror of “A Child’s Guide to the Hollow Hills,” to the superb occult noir of “The Maltese Unicorn.” Not only would what she pulls off in that one story alone make another writer’s entire career, I’ve actually seen it happen.

In their introduction to The Weird, Ann and Jeff VanderMeer write that Kiernan has “become perhaps the best weird writer of her generation.” There’s only two parts to that statement I’d question: Only weird? And perhaps? Weird fiction as a genre, if it is a genre, should be grateful to be able to lay even partial or intermittent claim to her. Caitlín R. Kiernan is the fulfilment of every weird fiction pundit’s dream of a transgressive, inclusive, brutally contemporary author who brings all the territory’s sub-genres bang up to date while ditching their historical baggage – yet she effortlessly transcends such categories and limitations, just as she effortlessly transcends every genre she’s cared to touch down in. Even after successive World Fantasy Awards and Bram Stoker Awards, she’s still a writer who can’t be honoured and recognized enough. Words fail me. But they rarely if ever fail her.

[Top]A review of This House of Wounds, by Georgina Bruce

This first collection from Georgina Bruce, published by Michael Kelly’s weird emporium par excellence Undertow Publications, gathers 16 short stories, including the British Fantasy Award-winning story “White Rabbit,” which comes at the tail end of the book. This House of Wounds provides Georgina Bruce with the grounding in print she deserves to complement her presence in the British fantasy and weird fiction scene. It also consolidates Undertow’s standing as the go-to house for the modern weird renaissance, because if you have authors like this on your list, you absolutely epitomize the cutting edge of the field.

This House of Wounds is simply a gorgeous book, with ravishing cover art by Catrin Welz-Stein to complement the contents. Fairy-tale motifs abound – Red Queens, sorcerous crows, Princess Beasts, Woods Kings – yet they’re frequently jump-cut past the reader in fragmented, discontinuous, subjective glimpses, like a mystic marriage of Angela Carter with J.G. Ballard. And the beauty and glitter is frequently the sparkle of streams of blood or the shine of polished bone – the wounds are there, laid bare and held open by retractors for probing and examination. This absolutely is not horror per se, but it touches on horror territory persistently. As the author has said, “I don’t think it’s possible to write about reality without encountering horror imagery and themes,” and if the collection ever touches on the British tradition of fey whimsy, it’s with an ironic, lacerating, mirror-sharded claw.

With many of the stories running at ten pages or less in the 179-page Kindle edition, there’s almost a suggestion of prose poetry, as though Rimbaud had ingested a bizarre infusion of Poe, or Kafka had taken a whiff of some Nineties Decadent opiate. That’s not just a matter of concision and density either. Georgina Bruce’s prose frequently rises to glittering pinnacles of decorative baroque flourish, without breaking off from the solid architecture underneath. “Deep and slick and fast and moving in a fluid dance, a flow of her body through trees, a flick of coal glowing within her thighs, a ribbon of flame rising and fluttering.” It’s anything but pedestrian.

For such a short and strongly characterized book, though, there’s nonetheless a great deal of variety. There’s dystopian science fiction à la Philip K. Dick (“Wake Up, Phil”), psychological horror (“The Art Lovers”), and a diversity of style from stream of consciousness to straightforward narrative. This is almost always going to be the case in a first collection, but there’s a uniformity of achievement and skill that balances the variety of styles and treatments. Georgina Bruce has gathered many points of departure in this book that she could set out from to map out different areas of her range, and it’s going to be fascinating to see which and how many she explores. For the reader, it’s going to be a fascinating and rewarding journey.

This House of Wounds is simply a must-have. You can digest it at one sitting, yet you’ll find yourself coming back to it again and again. Buy it; read it: you won’t be disappointed.

[Top]