My article on revisionist Lovecraftian fiction in the Los Angeles Review of Books

Revising Lovecraft: The Mutant Mythos

[Top]

My latest article in Los Angeles Review of Books: Reviewing Shadows and Tall Trees 7

Foreshadowing the Weird: “Shadows and Tall Trees 7”

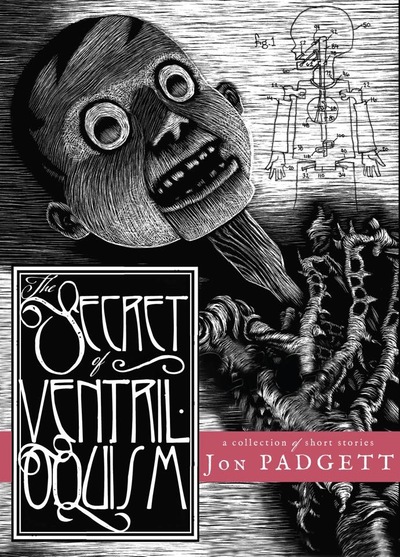

[Top]A review of The Secret of Ventriloquism, by Jon Padgett

The influence of Thomas Ligotti stalks large across contemporary North American horror and dark fiction, as Stephen King and H.P. Lovecraft once did and mostly still do. Jon Padgett is not slow to acknowledge his debt “to my friend and mentor, Thomas Ligotti, without whom this book would not exist.” Given that tribute, and the book’s focus on ventriloquist’s dummies, straight from the same toybox as Ligotti’s favourite emblems of puppets and dolls, a reader could be forgiven expecting a pastiche of Ligottiesque themes, like the Yog-sothothery that made so many careers in the immediate wake of the Lovecraftian revival. But how wrong they would be.

For one thing, The Secret of Ventriloquism contains exquisitely calculated prose chiseled sharply enough to cut off any suspicion of second-hand knockoffs. As an opener, for instance, “The Mindfulness of Horror Practice” is a short, simple, chilling parody of the kind of induction you might encounter in any tacky wellness session, retooled to evoke icy metaphysical sickness. “Murmurs of a Voice Foreknown” is the kind of boy’s own story that Stephen King could be proud of – finishing with one of the best five-word endings I’ve read in recent horror fiction. “The Indoor Swamp” is a sort of ghost-train horror ride guide that, once again, picks up all kinds of nightmarish existential dimensions along the way. And for another thing, as all that should suggest, Padgett has many more than one string to his bow, or manner to his mummery. There’s quite enough variety of tone, setting, and focus here to surprise and disconcert any reader, and leave preconceived expectations flopping and gasping in the cold black mud of Padgett’s imagination.

Despite the variety, there’s also some conspicuous continuity between stories, especially those directly concerning “The Secret of Ventriloquism,” which itself is a one-act play towards the end of the book. “20 Simple Steps to Ventriloquism” and “The Infusorium” both deal with the same theme, but in utterly different ways – the latter a sometimes brutal noirish ride through Padgett’s iconic hell-on-earth of Dunnstown. Then there are the awful origami dreams of, well, “Origami Dreams,” the grotesque affliction of “Organ Void,” the cold songs of Thin Mountain, and so on. And on. On far enough to outdistance any conceivable accusation of derivative work. Padgett is a chilling master in his own right. You’d be a dummy not to read him…

[Top]A review of The Rib From Which I Remake the World, by Ed Kurtz, ChiZine Publications

Noirish horror veteran Ed Kurtz‘s The Rib From Which I Remake the World rolls into town with one of the best titles of the year, and with all the barnstorming sawdust vigour of the travelling circus that provides its prologue. And the town it rolls into is Litchfield, Alabama, one hot wartime summer, when a “hygiene picture” as salubrious as any travelling medicine show sets up shop in the local fleapit cinema to entertain and instruct the handful of undrafted citizens, and, as it turns out, to do far more for, and to, them. House detective of the town’s only (halfway) decent hotel, George “Jojo” Walker, soon finds himself dealing with inexplicable happenings and dark secrets, which disinter his own dark secrets, and things get murkier and more unhinged from there on.

At this point, you might definitely be thinking Stephen King, or Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, but that’s an illusion that in due course is due to be snatched away like a magician’s cheap trick – and that’s as much of a spoiler as you’re going to get. Nothing is as it seems. What makes the story is the steady, relentless build that takes the narrative into new and completely unexpected territory, and the excellent, polished prose, segueing from Alabama drawl to Jacobean dialogue without missing a beat. As well as a terrifically ingenious and disorienting rationale for the whole awful situation, which makes for a hell of a reveal towards the end. And Kurtz has a great gift for characters, from the sympathetic and wounded to the sheerly evil.

The Rib From Which I Remake the World is the kind of book you can imagine entertaining the hell out of any supermarket-checkout King fan, while still managing to impress connoisseurs of horror and the modern weird renaissance. That’s quite a balancing act to pull off, and Kurtz does it without too much concession or condescension to either audience. ChiZine has also done a fine job on the production values and the artwork. Sadly it’s debuting too late for the summer reading list, but I can see this one on many bookshelves and favourites lists in the years to come. Recommended.

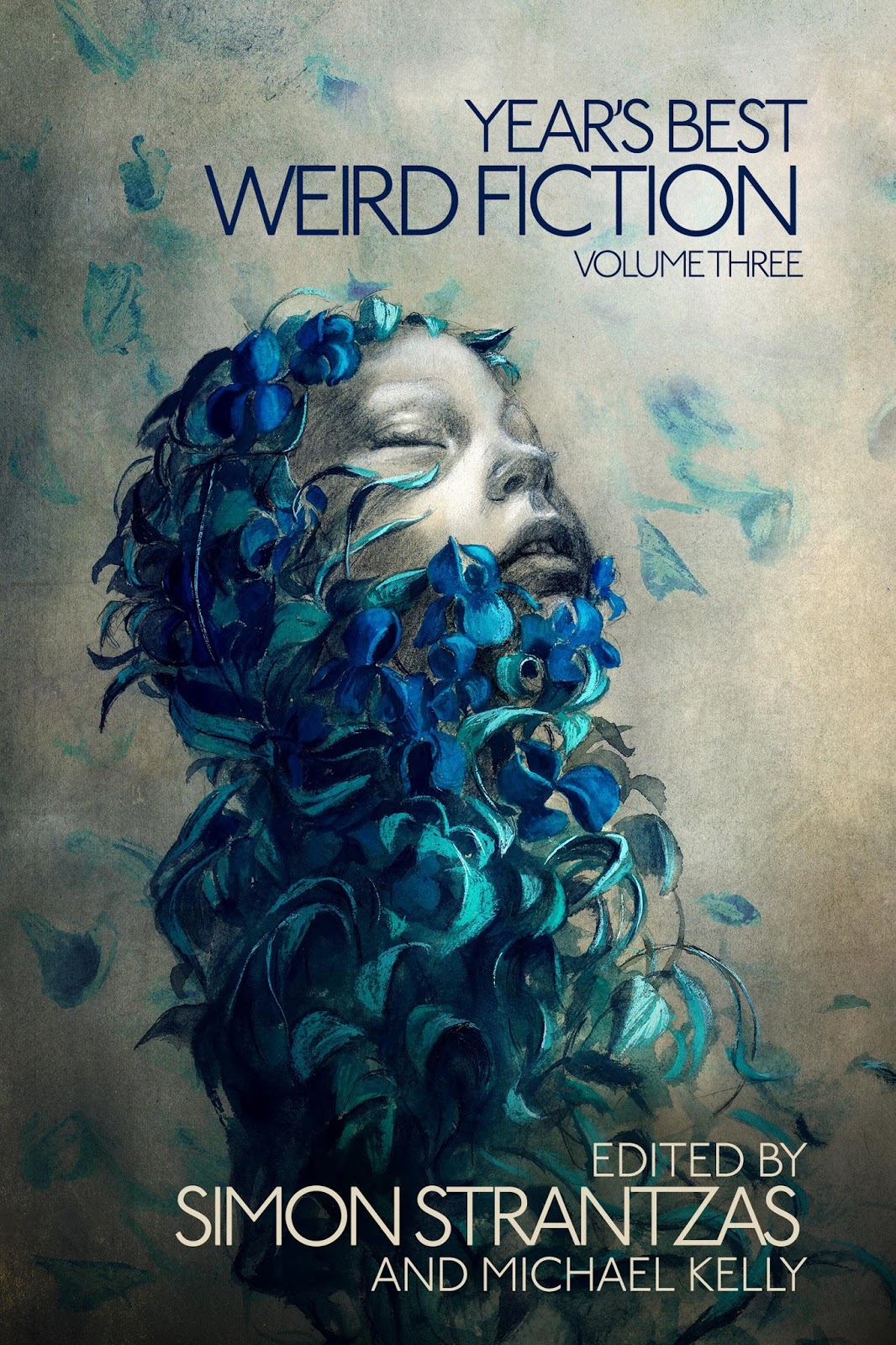

[Top]A review of Year’s Best Weird Fiction, Volume 3, edited by Simon Strantzas

The third volume of Undertow Publications’ Year’s Best Weird Fiction series comes lavishly garnished with expectations – and it doesn’t disappoint. For one thing, there’s plenty of meat: 19 stories, with, as Michael Kelly notes in his foreword, “almost no overlap with the other ‘Year’s Best’ anthologies.” For another, it’s edited by Simon Strantzas, “a dear friend, a great writer, and a sharp and inquisitive critic,” as Kelly says, and “an important voice in the horror and weird fiction communities.” With a new guest editor and “differing perspectives and ideas on what constitutes weird fiction” each time, each new YBWF has its work cut out to justify Kelly’s claim that “I believe this to be a vital and important annual volume.” As it turns out, though, no problem.

One of the distinguishing marks of Strantzas’s editorial policy for YBWF3 appears to be propulsive, front-loaded stories that roar off the starting grid. Example: “Abigail Gardner née Cuzak was sitting on the bathroom floor, thinking about the relationship that mice in mazes have with death, when a many-splendored light shot down from the stars like a touch of divine Providence,” the opening line from “Violet is the Color of Your Energy,” by Nadia Bulkin. It’s also a policy that has a lot to do with straight horror – poor Abigail, for instance, ends up having a far more personal taste of the relationship of mice in mazes with death than she or the reader would have wished, and Lynda E. Rucker’s poignant, chilling “The Seventh Wave” is probably best not read by parents of young children. In his introduction, Strantzas defends the position “that Horror and Weird are really the same,” even though weird tales “don’t need to have vampires, or werewolves, or psycho killers or possessed children or any of the familiar trappings,” and in fact next to none of the stories in this volume do.

Missing monsters and myths notwithstanding, Strantzas’s horrid weird is evidently in deep ongoing dialogue with its entire tradition. Robert Aickman, for instance, may be long dead, but his hitherto unpublished “The Strangers” gets into this collection because it surfaced recently in Tartarus Press’s collection with the same title of Aickman’s uncollected stories. “Seaside Town” by Brian Evenson featured previously in Undertow’s Aickman tribute anthology Aickman’s Heirs, and Aickman’s shade also looms in Robert Shearman’s subtly disturbing tale of pedophilia (or is it?), “Blood,” and “The Rooms Are High” by Reggie Oliver. Ramsey Campbell, meanwhile, appears as one of “those most affected by the boom” in horror fiction in the 1970s” with “Fetched,” a suitably ghastly tale of cold snobbish English disdain shading over into something much worse. That strong British leaning is confirmed by D.P. Watt’s “Honey Moon,” and Marian Womack’s tale of a post-ecpocalypse Cambridge, “Orange Dogs,” and you couldn’t imagine a more British title than “Visit Lovely Cornwall on the Western Railway Line” by Genevieve Valentine. I don’t think that’s bias, though – rather, I’m proud to say, it probably stems from the quality of the stories themselves. Fears of too much Brit in the mix, though, are dispelled with authority by tales like “The Devil Under the Maison Blue” by Michael Wehunt or Matthew M. Bartlett’s “Rangel.” And still the weird goes deeper…

All I’ve written might suggest a certain sameness in these stories: there isn’t. They’re strongly individualized, very distinct in tone, and they pass the Linger Test, staying in the mind when other tales have been forgotten. There’s one or two stories which will probably tweak my sensibility as touchstones for the entire genre, and it’s hard to imagine how critics or readers could properly evaluate the current renaissance in weird fiction without reading them, and this volume. Indispensable.

[Top]