A review of Apocthulhu

Written by Christopher Smith Adair, Fred Behrendt, Chad Bowser, Dean Engelhardt, Jo Kreil, Jeff Moeller, Emily O’Neil, Kevin Ross and Dave Sokolowski, from Cthulhu Reborn

What will happen when the stars do come right? That’s a question that has hung over Lovecraftian fiction practically ever since HPL laid down his pen at the end of “The Call of Cthulhu,” and that has haunted Lovecraftian gaming ever since Sandy Petersen’s first dips into the realms of non-Euclidean dicerolling. What will happen when Great Cthulhu does rise from the depths, or when the Whateleys finally open the gate to Yog-Sothoth and cleanse Earth life off the planet, or whatever other version of the End Times is in the fiction? Attempts to answer that question in a gaming context include Pelgrane Press’s Cthulhu Apocalypse, Evil Hat’s very wonderful Fate-based Fate of Cthulhu, and now Cthulhu Reborn’s Apocthulhu.

Australian RPG indie publisher Cthulhu Reborn was hitherto chiefly an archive site “providing a home for professional-looking typeset renditions of old, classic, and best of all free ‘Call of Cthulhu’ scenarios” released under Creative Commons licenses, so it’s not surprising that the book has made best use of publicly usable Lovecraftian gaming materials. (Their previous title Convicts & Cthulhu, transporting [sic.] Lovecraftian horror to early colonial Australia, has been recognized as “a historically- and culturally-significant publication by the National Library of Australia.”) The system in Apocthulhu has been almost entirely pieced together by Cthulhu Reborn’s Dean Engelhardt from existing D100 OGL material, very close to what was done for Arc Dream’s updating of the Delta Green platform. Indeed, strong hints of Delta Green recur often in the system, such as its use of personal Bonds as important pillars in a character’s losing struggle against the sanity-shattering impact of the Great Old Ones. That’s no bad thing, as Arc Dream-vintage Delta Green benefits from one of the leanest and most elegant investigative RPG systems around – one directly compatible, furthermore, with decades of BRP and d100 content for other systems, including material for Call of Cthulhu 6th and earlier editions. Apocthulhu’s mechanics are straightforward, well-tried, familiar to anyone who’s played in this genre, and occupy a relatively small proportion of the book, leaving most of its 330 pages for lavish setting detail.

Apocthulhu has inherited many of the virtues of its predecessors, yet still manages to stand apart from both Delta Green and Call of Cthulhu old and new, and be very much its own animal. For instance, the designers have put a lot of thought and work into creating a convincing resources and scavenging system for the post-apocalyptic hellscape, reminiscent if anything of the foraging mechanisms of the Fallout franchise. Potential “career” paths for survivors of the apocalypse are presented with varying levels of experience and depredation, depending on the severity of the disaster and the number of years since it befell Mankind. And rather than come up with yet another Lovecraftian bestiary, the authors have directed readers to the many that do exist, and instead whipped up eight sample apocalypses and three full scenarios, each with its own particular flavour of terror. Some of these are Mythos catastrophes involving canonical deities, or even hints dropped in some of Lovecraftian gaming’s most celebrated campaigns; others are entirely original with fresh-baked sets of very alarming horrors that more than make up for the absence of a standalone bestiary. Indeed, the game could easily be used as it stands to build a Walking Dead RPG, or to play any other non-Lovecraftian apocalyptic scenario. In a long and honourable lineage of post-apocalyptic RPGs from Gamma World onwards, Apocthulhu stands out for its grittiness and grimness, as well as for comfortably straddling the divide between Lovecraftian dread and other forms of horror.

One of its best tricks is saved, almost, for last. Apocthulhu has full d100-compatible rules for playing William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, in the longest and most detailed of its scenario settings, by Kevin Ross, which almost stands alone as a separate vehicle. Hodgson’s immensely distant sunless dreamscape, ruled by nightmare presences that besiege humanity’s last redoubt, was a formative influence on Lovecraft, but has remained very underused by RPG designers, no least because of the original novel’s turgid prose. Consequently, Apocthulhu and Kevin Ross are performing a real service to the horror RPG audience by disinterring Hodgson’s creations and framing them in such a well-proven, flexible system. Ross has said in one interview that the Night Land section is due to be expanded into a full-on standalone fork of the system, and that can’t come soon enough.

The overall standard of design and artwork for Apocthulhu is exceptionally high. Yes, there’s some style choices I may not agree with, and not every illustration is to my taste, but overall it’s at least as good-looking a book as anything you’d see from the top-line RPG majors these days. Apocthulhu is a testament to the quality and strength that modern indie game publishers can achieve in both form and content, and is likely to become many gamers’ choice for any kind of post-apocalyptic gaming, let alone Lovecraftian. You can plug it into reams of other existing games and game systems, or just ring the changes on the many options it provides by itself. The game has just gone live as a PDF on DriveThruRPG, with the print version being finalized as we speak, and you are warmly advised to snap it up. The stars couldn’t be righter.

A review of Malleus Monstrorum: Cthulhu Mythos Bestiary, by Mike Mason and Scott David Aniolowski, with Paul Fricker

Originally published in 2006, Malleus Monstrorum followed the tradition of S. Petersen’s Field Guide to Cthulhu Monsters (1988) in bringing the D&D Monster Manual and Fiend Folio approach to the Cthulhu Mythos. Chaosium has now doubled down on the great tradition of Call of Cthulhu monsters and malevolences: literally, since this is in two volumes. It’s certainly sumptuous. The slipcased two-volume hardcover edition is $89.99; the PDF is $39.99. There’s also a special leatherette hard-cover edition for all of $199.99. The cover and interior art by Loïc Muzy is literally mind-blowing, and the larger colour plates are superb.

There’s no questioning the compendiousness of the volume. You can see on the credits and copyrights page the extent to which the authors have ransacked the estates of various Cthulhu Mythos writers – Eddy C. Bertin, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Walter C. DeBill, August Derleth, Robert E. Howard, T.E.D. Klein, Henry Kuttner, Brian Lumley, Gary C. Myers, Richard F. Searight, Clark Ashton Smith, Donald Wandrei, Colin Wilson – to reframe just about all of their creations as CoC creatures. Every variation on more or less canonical creatures and divine beings is rung.

All this is a summary of the new edition’s many excellences. Those are self-evident, and any problem I have with its approach is purely personal. All the same, I do have very specific issues with it.

For one thing, there’s a certain schizophrenia in its approach. The introductory essays give extensive advice to Keepers on presenting Mythos creatures ambiguously, ringing the changes on their descriptions, ideally never referring to them directly by name unless you want to skip over them with as little time and trouble as possible. Yet you have umpteen specific, concrete articulations of the monsters in the most concrete terms, exhaustively particularized. Is that going to boost Keepers’ imaginations, or channel and tramline them?

Then there’s the more than a little gung-ho approach to Mythos deities and demigods. For some historical perspective on this, way back in an interview with Different Worlds magazine in February 1982, Sandy Petersen talked about the design process behind the original Call of Cthulhu: “At first, I tried to simply write up all the different deities as if they were normal monsters, listing SIZ, POW, and so forth for each different god, along with some brief notes about the cult, if any, of that particular being. I quickly discovered that this approach was unsuitable, since the scores I gave the various monster gods was too completely arbitrary, and the possibility of harming one in the course of play too remote for their statistics to really matter… I listed each god according to its effects when summoned, its characteristics, its worshipers, and the gifts or requirements that it demanded of those worshipers. This approach was eminently workable, and I was quite self-satisfied at its conclusion. Later on in the development of the book, Steve Perrin wanted to re-include the statistics for the deities, and thus the STR, INT, etc. of Cthulhu and the rest are now included in the game again.”

I side with Sandy Petersen on this one. Not only is the prospect of damaging a god just a little bit ridiculous in any context, it absolutely goes against the core Lovecraftian thesis that humanity is less than ants before utterly powerful and incomprehensible deities. Call of Cthulhu, needless to say, does not implement that line of thinking in its system, and Malleus Monstrorum definitely doesn’t. For instance, “Mythos deities are not (in the main) omnipotent.” That isn’t exactly the impression that one gets from Lovecraft’s descriptions of Azathoth, or even hints about Yog-Sothoth. “If hand-to-hand melee with an Old One is what you are going for, then cool – this is your game, so go for it.” Well fine, except that your game is likely to be lacking in both Lovecraftian and horror – something of a problem with a game of Lovecraftian horror. Petersen said about Call of Cthulhu in the same interview, “in the game’s present form, it plays much like an adventure mystery, such as the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark.” Nothing wrong with that, except that it misses out so much of what made Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos so unique and so genuinely terrifying.

The hobby has grown a lot since the early days of Call of Cthulhu and Petersen’s interview, with a whole raft of different approaches and styles. Despite its seven reiterations, I’m not sure that Call of Cthulhu itself has grown all the way with it. Mythos gaming has grown out and ramified in all kinds of directions from its original CoC roots, but Malleus Monstrorum doesn’t seem to have fallen far from the tree. And I wonder if this is going to leave Chaosium with an audience burnout problem, where players take up the game in a flush of adolescent enthusiasm, then drop it later because it has only limited room to grow up with them. Other RPGs, not least Delta Green, are as adult as they come, and supported by robust fan bases. For me at least, Call of Cthulhu still looks to be ploughing the (admittedly well-worn and well-tried) furrow of monster-bashing, and going monstrously monstrous on monster adversaries with a monster volume of material. Powergaming, levelling-up, minmaxing and twinking has worked well enough for D&D, after all, so why not keep pushing those same approaches For those players who game to indulge their wish-fulfilment power fantasies, Malleus Monstrorum provides whole gods that you can squash.

Of course there’s probably a bit of that kind of player in all RPGers, but there are other styles of play too, and powergaming is particularly jarring in a genre that is supposed to be about helplessness. I mean, one of the prime attractions of Call of Cthulhu was supposed to be that the more you encountered the Mythos and its creatures, the more deranged and hence helpless you became. Yet a big target HP total for a god makes it just another end level boss to bash with a bigger bashy thing. Face it, hit point stats are there so you can hit things and grind up. Hitting gods may work in D&D, but it’s hardly recommended in most other less powergaming-focused systems. If you can hit something, you can kill it: ergo, it’s only scary to a certain extent. Lovecraft’s deities and demigods suffered from no such limitation.

Also, look at the sheer crunchiness of Malleus Monstrorum. It’s all compendious stats and detail. So many RPGs now are launched as rules-lite in one form or another, including many independent Cthulhu hacks. Delta Green’s essential system rules run to just 96 pages. Fate Condensed runs to just 68 pages; The Cthulhu Hack runs to 52 pages. And One Page Cthulhu is… well. Yet, CoC’s DNA is solid BRP, just like Delta Green. It just goes to show the different ways things can go.

My feeling is that, if a large slice of the RPG community has moved away from stats-intensive, crunch-heavy systems, it’s for a good reason. But for those whose appetite for sheer crunch hasn’t been satisfied by Warhammer 40,000, we have in 7th edition Call of Cthulhu 288 pages of Investigator Handbook and 448 pages of Keeper Rulebook. And yes, 480 pages of Malleus Monstrorum.

H.P. Lovecraft himself wrote: “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” But in Malleus Monstrorum, everything is known, known: ground out in stats right down to most exhaustive, exhausting, tiresome detail. Where’s the mystery, the fear, in that? Azathoth has 500 POW, wow! That’s really Powerful! Like, that means that you actually need 50 average human magic practitioners to equal the Demon Sultan principle of all Creation and embodiment of all the forces of the entire Universe. Feel strong, you 50 dudes! And this is supposed to be the world’s Number One horror RPG.

Look at the alternative approach in Trail of Cthulhu: “we have included only two statistics for gods and titans, the additional Stability loss and Sanity loss suffered when they are encountered… Everything else is and should be entirely arbitrary and immense. Fighting a Great Old One is like fighting an artillery barrage. It doesn’t matter how many shotguns you brought.” Sure, the introduction to Malleus Monstrorum also states that: “the Cthulhu Mythos is unknowable to humanity. What scraps of information are known are drawn from rare and fragmentary texts, conversations with wizards and witches, and from life-altering exposure… What “canon” exists is loose and unreliable.” Yet that declaration seems to be working at the very least at cross purposes with the actual contents of the book. There’s an awful lot of very emphatic stats and numbers for stuff that is supposed to be so unknowable. And ultimately players are likely to be most guided by the mechanics.

Chaosium’s recent revival has produced some truly fantastic Call of Cthulhu products: Berlin – The Wicked City springs to mind; or Harlem Unbound. And there’s no denying the sheer material quality of their current reborn product range. But I do have big reservations about a large slice of their approach, and Malleus Monstrorum exemplifies those reservations. For me, it succeeds in being at once both overpowering and underwhelming. Its sheer physical quality, and quantity, masks significant conceptual shortcomings. It’s the Super Size big-box belly-filler for an audience whose tastes have grown a lot more diverse and sophisticated. Sometimes more really is less.

That said, anyone like me who enjoys a lower-key, more complex and nuanced approach to their RPGs has got to face up to one thing with Lovecraft: Is he more famous for his philosophy of pessimistic cosmicism, or for the monsters he created? I doubt he’d have anything like the name brand recognition, or the long tail of RPGs following on his legacy, if it wasn’t for tentacular Cthulhu and all the other creatures he used to embody his fears. Perhaps it’s unfair to beat Malleus Monstrorum up for an issue that starts with the author himself.

Anyway, that’s Malleus Monstrorum for you. It doesn’t incorporate much of the new narrativist developments in RPGs. It pushes the original, traditional, simulationist approach, and 1980s attitude to monsters and challenges, just about as far as it can go. So long as you’re happy with those limitations, this is as good as it can possibly get.

[Top]My new review of Mike Allen’s “Aftermath of an Industrial Accident: Stories” over on Ginger Nuts of Horror

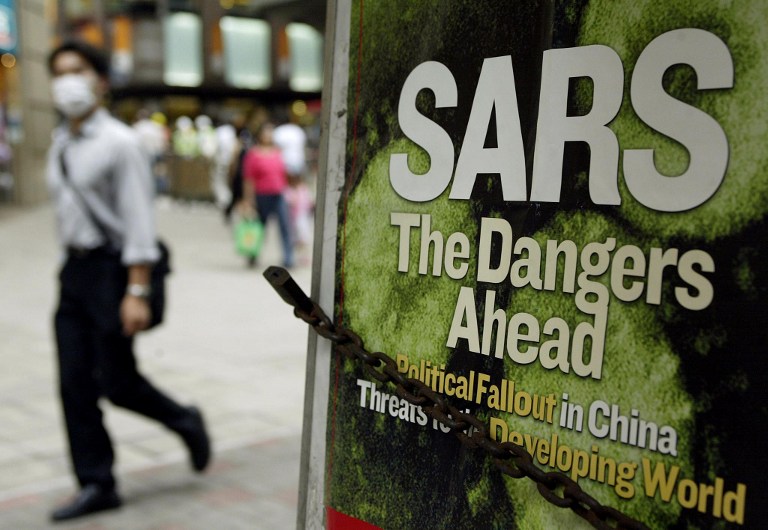

Living through SARS

The first inkling I had that the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong in March 2003 was serious was when my colleague turned up to work wearing a heavy filter mask. It wasn’t the discreet courtesy paper rectangle: it was a respirator-style cone with two great round filters on either side. She wore it the entire time as she sat at her desk, lifting it only to eat from her lunchbox.

My first reaction was anger. Here we were, working as a team, supporting each other, exposed to the same work environment, taking the same knocks, sharing the same risks and rewards in our Hong Kong PR agency, and yet here she was treating the rest of us as plague carriers. How could she break the team spirit? The only exoneration I could think of was parental pressure. Like most younger Hong Kongers, she probably lived with her family, forced to share living space by the high property prices. With typical Cantonese family sense, they doubtless had put pressure on her to keep contamination out of the home and screen out the threat from the Outside. That rationale eased my anger only a little.

I had nothing much to leave Hong Kong for in 2003, and by the time I finally realized how serious the situation was, I had lost the opportunity. SARS never quite made it into the pandemic league, since it never spread far enough. Only a score of countries were affected, and the majority of the 8,098 reported cases were in southern China. Still, it caused worldwide panic, and its prognosis was considerably grimmer than coronavirus: an average fatality rate of 9.5% of those infected, compared to at most 3.4% for COVID-19. Left unchecked, it could have killed 670,000 people in Hong Kong alone. And Hong Kong, one of the most densely populated territories anywhere at 6,659 people per square kilometer, was isolated from the rest of the world in 2003 and left to deal with SARS by itself.

Spring in Hong Kong is a humid season, and March 2003 was no exception. With its high population density and inward-looking character, Hong Kong is a claustrophobic environment at the best of times, fomenting cabin fever besides other contagious diseases. The thick low clouds hanging over the city added to the impression of a seething cauldron with the lid crammed down. Already it was effectively impossible to leave the city by any ordinary means. The World Health Organization issued an emergency travel advisory on 15 March, providing “emergency guidance for travellers and airlines.” Many countries were by that time already restricting or refusing to admit flights or passenger traffic from Hong Kong, and the WHO advisory signalled an effective global cordon sanitaire. No one could get out.

Isolation was the strongest and most immediate impression of the outbreak. The sense of imprisonment was as oppressive as the creeping dread of the disease itself. The SARs virus, of course, was invisible, and actual cases were rapidly quarantined. News reports only added to the surreal air of a nightmare you couldn’t waken from. The WHO continued “to recommend no travel restrictions to any destination,” and governments worldwide insisted that there would be no embargo of Hong Kong – while cutting flights, denying entry, and instituting a de facto embargo of ferocious comprehensiveness. Their efficiency contrasted with the Chinese authorities – hustling SARS patients out the back of hospitals when the WHO inspectors came calling, to bring the headline case numbers down. China’s venal autocracy had let the disease get out of hand in the first place, and we knew we could trust nothing that came over the border. The official lies, evasions and half-truths added to the all-pervading sense of unreality. Hong Kong resembled a ghost town, populated by phantoms. Streets were almost empty except for occasional wraithlike figures in masks. Mists and fogs worthy of any Hammer horror film clung to the peaks.

In the circumstances, we knuckled down and rode it out. We simply had no choice but to get on with stuff. We couldn’t get away, and we couldn’t be terrified 24:7. Fortitude came easy in those conditions. Offices stayed open, and work went on, though with precautions. There was never the draconian response in Singapore, where all quarantine cases were required to have a webcam connected at all times and faced random government checks to verify their presence at home, as well as to check and record their temperatures twice daily on camera if required. We went out, we drank, we partied, we went clubbing, because when we were already so much at risk, what did a little more matter? It was defiance, giving the finger to the rest of the world that had conspired, without a formal coordinated policy, to trap us there.

Besides, if we thought we had it bad, there was always someone worse off to compare with – like the residents of Amoy Gardens, the outbreak’s worst hotspot, confined within their apartment buildings behind police cordons while tenant after tenant became infected. As streetwise Hong Kongers, we naturally assumed that the cause lay in shoddy building work by the developer and poor safety standards. Sure enough, most of the contagion was traced to leaking waste pipes spraying waste water into the complex’s breathing air, but not before over 320 people had been infected. In April, the residents were transferred to quarantine camps in remote districts.

Then there were the doctors, nurses and healthcare workers, always the frontline casualties in any battle against disease. You can still see in Hong Kong Park above the harbour a poignant memorial to eight doctors, nurses, and ward attendants who died from the disease while fighting its spread. They were the community’s local heroes, in contrast to the leadership, disdained at the best of times.

Quarantine, like war, is months of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror. Add to that frustration. Much of our pushback against the official guidance on self-seclusion in Hong Kong during SARS was pure frustration, rather than deliberately flouting authority. In any event, we had plenty of time to build up a hell of a head of frustration. On 23 May, the WHO lifted its Tourism Warning for Hong Kong and Guangdong, and the moment the informal blockade was lifted, I was on my way to Singapore.

That was our limited little plague over. Hong Kong’s final toll was 1,755 confirmed cases and 299 deaths from SARS. Samples of the SARS virus are still among the few classified as Biosafety level 4 organisms by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), alongside the Ebola and Marburg viruses and ricin.

What were my takeaways from SARS for the coronavirus pandemic? National sovereignty is a great way of ducking your wider responsibilities: that was one. The Communist Party of China can never be trusted to put the lives of its own citizens or the wider global community before its own monopoly on power: that was another. But if I learned any personal lesson from the experience, it was the value of patience. Any courage we showed under SARS was obligatory. We had no choice. We weren’t going anywhere. We had no agency, no power to alleviate the situation. We just had to get through it.

In a society powered by instant gratification, patience and forbearance are habits that take some reacquiring. We’re told constantly that our slightest twinge is worthy of attention, that we’re entitled to have our most insignificant discomforts and discontents pandered to. We confuse our entitlements with our rights. We feel entitled to have our fears pandered to instantly, as with our desires. SARS at least put that in perspective. It helped immunize me against fear. Now at least I’ve been through it and come out the other side. So, hopefully, will most of us

[Top]A review of The Foulness Island Vanishings, by Glynn Owen Barrass & Friends

Stygian Fox is producing original Call of Cthulhu 7th edn. scenarios at a rate of knots nowadays, and this Second World War Era volume by the illustrious (and industrious) Glynn Owen Barrass is a shining example. The Foulness Island Vanishings: A Corrupting Infiltration In A Time Of War, in full, is, unsuprisingly, set on the real-life Foulness Island off the south-eastern coast of England in 1941, and mingles wartime paranoia with far more malign influences. The whole scenario breathes a very strong sense of time and place, like something out of a Second World War propaganda film – perhaps Went the Day Well? with its bizarre breakdown of English village life – and contains a lot of useful setting information that could be applied elsewhere. And although the scenario is fully written out for CoC 7th edn., it doesn’t look hard to tweak for Achtung! Cthulhu or other appropriate systems.

As for the scenario itself, its 84 excellently illustrated colour pages make full use of the island’s diverse locations and inhabitants in unveiling the story of a very strange infestation indeed. The maps, handouts, and house plans match the high visual quality of the rest of the book. The horror tropes are at times pretty unpleasant, and the scenario carries a Mature Gamers rating for a reason. There is certainly plenty of human evil on display, redolent of wartime atrocities, but the Unnatural brings in its own level of veriest awfulness to boot. By the end, Investigators certainly won’t feel that they’ve had a drab wartime ration of adventure and horror.

If Stygian Fox continues its present tear of high-quality Cthulhu Mythos material, I think we’ll all be the better for it. Production values are superb, and easily match the quality of the core 7th edition materials. And Stygian Fox’s choice of subjects seems to be sweeping an attractively wide field. For now, take a mental time-out from sequestration to enjoy another time and place of isolation and menace, and experience the foulness of Foulness.

[Top]A review of Dead Light and Other Dark Turns, by Alan Bligh, Matt Sanderson, Lynne Hardy and Mike Mason

If you’re driving in backwoods America, don’t stop for anything. That’s the lesson of Dead Light and Other Dark Turns, Chaosium’s latest scenario book for the Call of Cthulhu 7th edition rules. Alan Bligh and Mike Mason’s Dead Light should already be familiar to many of Call of Cthulhu aficionados as it was first published in 2014. The original edition appeared in dual-statted form to allow players to have a taste of the new 7th edition rules in progress. This new version fine-tunes and fully reskins the scenario for 7th edition, while also updating the materials to the current Chaosium style and level of quality with brand new artwork. It also includes a brand new scenario in the shape of Matthew Sanderson’s Saturnine Chalice. The old edition was just 32 pages: the new one is 90 pages, including extensive handouts. The scenarios are written for classic era 1920s CoC, and unfold in typical Lovecraft country, but could be rejigged for other periods and locations with relatively little effort.

Back at its first release, Dead Light was hailed by at least one reviewer as: “the best title released by Chaosium in years.” Since then, Chaosium has arguably upped its game and has been churning out high quality work in spades, but Dead Light especially has an original and unusual nemesis whose characteristics help add a nasty tinge of moral squalor to the cosmic horror. Saturnine Chalice may seem a little more familiar in its choice of threats, at least on the surface, but the clue trail is (optionally) puzzle-based, which makes for a different slant on typical gameplay, and the unfolding mystery is rich in head-fuckery. There are also shorter seeds for road trip encounters and adventures at the end of the book.

This is definitely a worthwhile addition to the roster of 7th edition CoC scenarios available, especially for shorter more stand-alone adventures. At the inconsequential price that Chaosium is asking for it, it’s a steal even for owners of the original Dead Light. Recommended for Call of Cthulhu players old and new.

[Top]A review of New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, 2nd edition, by Tom Lynch, Christopher Smith Adair, Oscar Rios, Kevin Ross, Keith “Doc” Herber and Seth Skorkowsky

As the blurb for Stygian Fox’s Kickstarter explains, “Miskatonic River Press released New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley to great acclaim and it quickly became a favourite among Call of Cthulhu Keepers.” This is essentially a resurrection of a much-loved scenario book, originally published in 2009 as a follow-up to Chaosium’s 1991 Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, which also gives an opportunity to see how RPG publishing has moved on since Chaosium’s 1991 effort and the original New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley. Tom Lynch’s personal dedication to the book is a heartfelt reminiscence of Keith Herber, CEO of Miskatonic River Press, lamenting the sad demise of the publisher and the publishing house. Keith Herber was a powerhouse of scenario-writing in the early days of Call of Cthulhu, producing almost 50 scenarios for Chaosium in the 1980s and early 1990s, and it’s not surprising that his tragically short re-emergence as founder of Miskatonic River Press in 2003 has left a lasting impression on the modern Lovecraftian gaming scene. The whole exercise obviously has had a lot of love lavished on it, and Call of Cthulhu players are the fortunate beneficiaries.

The original six scenarios in New Tales have stood the test of time and are reprinted in full, freshly rejacketed and statted up, not only to run on Call of Cthulhu 7th edition rules, but also to bring their presentation up to the kind of standard we’ve come to expect from the newly reborn Chaosium and their associated projects. There’s an additional new scenario from Seth Skorkowsky, “A Mother’s Love,” extending the book’s coverage to Innsmouth with an appropriately twisted tale of miscegenation and mayhem. I’d still be happy to play these scenarios through with earlier Call of Cthulhu rules, or indeed with Trail of Cthulhu or other systems, because they focus so much on drama and story rather than pure game mechanics. There are plenty of human protagonists and antagonists with their own mundane agendas that can trip up the players as effectively as any scheming cultists. The unnatural horrors that do appear are a refreshing mixture of new takes on Cthulhu Mythos staples and original creations, and should be enough to stimulate the most jaded Call of Cthulhu grognard.

The real surprise for anyone familiar with the black-and-white layout and fairly limited art of the original is the visual presentation of the 2nd edition. Stygian Fox has done a frankly incredible job on the production values. The maps of Arkham, Dunwich and other favourite Lovecraftian locales are the best I’ve seen, even when set against the superb cartography in the latest Chaosium products, and the handouts and period prop pieces are equally luscious. Stygian Fox was working off a Kickstarter that closed at roughly 400% of its target, and the money has been well spent. There are even terrific multi-page handouts for pre-rolled characters. “The original is black and white and 130 pages,” Stygian Fox noted. They managed to expand the final publication to 240 full-colour pages.

Would I recommend this book to anyone who had the original edition? In a heartbeat. It’s not just the extra material and the restatting of the stories to Call of Cthulhu 7th edition. It’s the superlative production, which is bound to be usable in other campaigns. Indeed, if you want to run a 1920s campaign in canonical Lovecraft Country, I’d advocate this book as a go-to for mapping out all the core locations – Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, Kingsport, and environs – in immaculate style. The full-colour double-page panorama of Arkham, for instance, captures that Mythos-ical city exactly as I’ve always imagined it. Furthermore, Chaosium still hasn’t released updated 7th editions of many of its own classic Lovecraft Country scenario books – such as Keith Herber’s original H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham and H.P. Lovecraft’s Dunwich. That puts New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, 2nd edition to the fore as the Number One CoC 7th edition canonical Lovecraft Country supplement – a position it full deserves to occupy. It’s a testament to the current health and vigour of Call of Cthulhu gaming, and a worthy tribute to its progenitor.

A review of Petals and Violins: Fifteen Unsettling Tales, by D.P. Watt

Introduction by Peter Holman, Afterword by Helen Marshall

D.P. Watt is already a Shirley Jackson Award nominee for his 2016 collection from Undertow Publications, almost insentient, almost divine, so he’s well established among readers of weird and dark fiction. In fact, he’s written 8 books by my count, including this one. Despite the fact that Petals and Violins comes heavily flagged as a chunk of the Weird Renaissance, with an afterword by Helen Marshall, there are plenty of stories here that would appeal to the most recherché traditional ghost story enthusiast. D.P. Watt is not especially a representative of any particular school or trend, and very much his own animal. The author has said in one past interview that “The process of composition changes with each story, and I have no particular allegiance to any movement, nor indeed anything as well-formed as a technique that I can deploy. My writing seems now to be more driven by scenes that emerge as I am working.” (Bibliophagus, 2015) That’s certainly what comes across here, and it’s a process that’s to be welcomed.

The opening story, “Blood and Smoke, Vinegar and Ashes,” for instance, is a tale of folk alchemy in rural Poland, and the remarkable results achievable by the quoted ingredients and others; M.R. James could have well produced his own version of the theme. “Mizpah” and “The Magician, or, Crab Lines” also have that flavour of folk horror, in narratives closer to Daphne du Maurier’s The House on the Strand. (Indeed, du Maurier’s blend of psychological tension, the paranormal and supernatural, and a very strong English sense of place and the past, finds substantial echoes in D.P. Watts’s work.) The most ambitious, and distinctive, story in the book is “Conflagration: Immoral Vignettes,” a slideshow of historical, tragical tableaux featuring writers from 1895 to the present, from August Strindberg to Tadeusz Kantor. D.P. Watt has certainly experimented plenty with form in the past, notably in his novella The Ten Dictates of Alfred Tesseller, and this is the most stylistically extreme story in the collection – and, in my opinion, one of the best. I could go on and on about the value of using history and aesthetics as imaginative resources, instead of typical horror set-dressing or weird psychobabble, but it definitely works. Any more traditional reader who balks at this approach is advised to stick with it. “The Pedagogue, or, They Muttered” is more in the Lovecraftian vein of pedantic academia touching cosmic horror, while “A Species of the Dead” is closer to psychological horror, where the disturbance of the natural order is purely social and mental.

It goes without saying that a writer this experienced is fully on top of his craft, and can turn a phrase or string a narrative with hooks. Weird or dark fiction, ghost stories, horror or surrealism, whatever you call it, this loose cluster of genres is in rude good health in Britain right now, and D.P. Watt is a tremendously accomplished practitioner. Petals and Violins is a box of dark gems.

Nationalism and Internationalism

Friday the 13th, and the Fates are laughing. Talk about bad timing. The most divisive, damaging UK election in decades yields its results on the most inauspicious day. Only a figure as tone-deaf to irony as to honesty and decency could have picked such a date. Who the gods would destroy…

Yes, there were signs of hope, when both Scotland and Northern Ireland elected progressive nationalist majorities. Yet were they beneficiaries of exactly the same forces that had mortally damaged the United Kingdom as a whole? Is one nationalism bad, and the other nationalisms good? Are nationalisms acceptable when they support progressive, left-leaning policies?

There’s one obvious lesson, which is that nationalism is a recipe for disintegration. There are few modern nation-states that are truly homogeneous enough to embrace chauvinist identity politics without risking internal fragmentation. Demagogues may seek to profit from that fragmentation, but it’s unlikely to do the nation-state in question much good. The so-called march of populism has mostly involved the manufacture of internal resentment of one part of the population against another as much as it has involved any genuine popularity. Demagogues are just becoming more ruthless about playing internal divide-and-rule, at whatever cost to their countries. Unfortunately, nationalism gives them every basis for doing just that.

From the former Yugoslavia to the current soon-to-be-disunited-Kingdom, it’s self-evident that nationalism within the nation-state on the model we’ve inherited from the 19th century destroys states, just as pan-Germanism destroyed the Austro-Hungarian Empire. There never was a “Great Britain” that wasn’t already a British Empire, and there never was a “British” nation that didn’t incorporate a diverse mix of traditional polities, ethnic stocks and religious traditions. The United Kingdom’s name is a great deal more honest than any attempt to pass it off as an ethnically distinct nation: it is a monarchical government that has united, sometimes by legal means but mostly by force, a great many lesser entities under its sway. Even before the modern, belated absorption of post-colonial immigrant populations as some kind of recompense and acceptance of its imperial legacy, “Great Britain” incorporated numerous different languages, ethnic sub-groups, and conflicting legal and religious traditions. Anyone calling it one nation is assuming a lot, and usually with an agenda. Try asking Chechens or Kurds or Tibetans if the modern nation-state is a sufficient basis for sovereignty.

The nation-state was not even the highest power in the supposed golden age of nation-states: it was simply a historic pretext or springboard for the acquisition of multiracial, multiethnic, polyglot empires, which have been the true Great Powers from ancient Persia and Peru on down. Once things had moved on from the march of Christendom to the Nation in Arms, the nation-state became the machinery for agglomerating and subjugating nations. Yet that national basis for conquest, competition and expansion put a time bomb at the core of the nation-state. The contradiction between the idea, or inherited tradition or myth, of a nation, and the realities of state power, is the kind that torments a mind devoted to the myth of nationhood to near insanity – it’s only resolvable in the end by the typically fascist rejection of thinking and critical analysis, and expiation through destructive and suicidal aggression.

There never was a Great British nation. Great Britain was a multinational empire from Day One: frequently at war with itself, always mixed and heterogenous. Nostalgia for greatness based on that kind of empire is obviously, insanely, at odds with nationalist enthusiasm for a sovereign British nation-state. A “Great” Britain that gives way to nationalism will find itself both split apart and ground between the far larger continental powers that are truly able to project geopolitical strength – on a level that one slice of the British population evidently still wishes they could, but can’t. You can count on the fingers of more than one hand the number of Chinese provinces whose individual population now exceeds that of the entire UK. Britain can only pander to such powers – exactly what it’s been doing since the Second World War, towards America.

Any attempt to recover national greatness is therefore blindly, insanely self-contradictory and destructive. And needless to say, the atavistic tribalism of collective emotions whipped up under the guise of nationhood makes a pretty poor mix with the apparatus of states. The adulation of nationhood was almost certain to transform nationalist states into killing machines on a massive scale, because any contradiction between the power of the state and the felt greatness of the nation had to be suppressed and eliminated, which ultimately meant exterminating the subject peoples – just as Nazi Germany did in the conquered territories of Eastern Europe. Napoleon’s Empire, the military realisation of the Nation in Arms, could only truly accept citizenship for the French and subjugation for the rest.

The nation-state does present one seductive feature for a certain section of the population: The abdication of citizenship. Weariness with the entire political process has been one of the hallmarks of the Brexit “debate,” and it’s all too easy to see where this can end. It’s been well said that fascism is not the people’s abandonment of democracy, but their abandonment of politics. They simply want to be the passive objects of government, not active, thinking participants as citizens. A prime minister who hid in a fridge was the perfect figurehead for what happened: the election of the xenophobia/selfishness/irrendentism/sloth that dare not speak its name. It was an election where voters really did not want to know, or be reminded of, or face up to, or be held to account for, let alone be shamed by, what they were voting for. An uncounted number were probably voting just for the opportunity to forget and give over the responsibility of thinking for a while. It looks like another of those English fits of absence of mind like the one where we acquired the enormous moral burden of the British Empire: a concerted effort of the left hand not to know what the right hand was doing. For an era stuffed with people trying to forget that their actions had consequences, it was the perfect poll.

Given the values on show, that’s hardly surprising. Only a few, more or less unhinged, right-wing figures – usually ideologues rather than practising politicians – actually admit to valuing and endorsing cruelty, bigotry, selfishness, and aggression for their own sake and on their own terms. Far more voters like to get the benefits without admitting the nature or the consequences of what they supported. That arch-priest of “the art of lying,” Adolf Hitler, preached the power of the Big Lie to overwhelm the judgment and discrimination of small minds, but it’s easy for small minds to play small tricks of moral sleight of hand to cheat their own consciences with, especially when no one is holding them up to judgment. (Small minds meaning uneducated or unexercised minds unable or unwilling to judge or evaluate.) This also neatly allows them to evade moral responsibility for their actions.

Even the Labour Party embraced the tactic. Having played Tory-lite in the Blairite era to provide a less repugnant version of pre-Crisis bonanza capitalism, it plugged the same tactic with Brexit, and tried to provide a more fudged, digestible version of the same prejudices and insularity. If the UK Labour Party couldn’t fight the Tory narrative that Polish plumbers and other immigrants were to blame for the woes of the English working class, then what legitimate claim did it have to be a party of the international labour movement? How shamefully far the British labour movement has fallen from the days when its heroes marched off to fight the Fascists in Spain.

Did the British working class have just cause to embrace nationalism to defend itself against globalization and job-stealing immigration? That debate falls down on the basis that it’s the modern Conservative, populist Big Lie. The myth left fact behind long ago. I don’t see much need here for a moral panic about the dangers of the Internet and fake news either: ever since the earliest approximations to a mass media, from the pulpits of Paris in 1572 to the Vienna of Karl Kraus’s “destruction of the world by black magic,” people have always followed what they wanted to hear. Certain aggressive outliers were more adroit and ruthless in mastering the new media, that’s all, just as highly motivated outsiders always have been. And they had material ready to hand in the form of fear and insecurity, the dry tinder of nationalism.

Nationalism is a collective expression of individual paranoia, facilitated by exactly the kind of fear and insecurity that propagate paranoia on the individual level. A demagogue’s first goal is to create paranoia, because fears overwhelm facts. Paranoia is delusional by definition; it also is one of the easiest abberant pathologies to foster and create on a mass level. Ignorance fuels suspicion, suspicion fuels paranoia, paranoia fuels fascism. And fascism is always going to be the totalitarianism of the stupid, because it appeals to the kind of insecure nature which views discrimination, thought, analysis, as a direct threat, to the kind of undifferentiated, syncretic identity that they cling to. You can see a whole lot of what Gerard Manley Hopkins once described as: “what came in with Kingsley and the Broad Church school, a way of talking (and making his people talk) with the air and spirit of a man bouncing up from table with his mouth full of bread and cheese and saying that he meant to stand no blasted nonsense.”

The Labour Party certainly had very few facts and arguments to hand to counter the nationalism of 2019 apart from those that it stole from the Conservatives. On the critical demographic and social divisions in England prior to the 2019 election – town versus country, young versus old, educated versus undereducated, internationalist versus nationalist – Labour had nothing to offer. Rich versus poor? Fine, except that left-wing conspiracy theorists were reduced to seeing the entire Leave : Remain debate solely in terms of two conflicting conspiracies of the rich.

Selective preference for any particular group, party or faction or class within a society, however disadvantaged, is the easiest thing to manipulate in the world, and is also the easiest thing to turn into chauvinist hostility when transferring to a different context. Robespierre’s sans-culottes were the cannon fodder for Napoleon’s armies. Class war is dead. Not because there are no disadvantaged classes, but because the only winner from such a war is the strongest warlord. A society built on the sovereignty of all has to work for the benefit of all; neither the rich, nor the insulted and injured. No state or community is perfect, and the balancing out of different claims is exactly what a state or society is about. But none can claim that any part enjoys preference or precedence by right – for reasons I’ll go into below.

Hating the rich is a fine and honourable pursuit but it is no substitute for freedom. and it takes no great perspicacity to see that the left has pivoted way over towards the Equality leg of the Liberty/Equality/Fraternity trinity at the expense of the other two, and worse, rewritten that Equality into primarily economic terms, not political terms. The 19th-century socialists may have been too in awe of industrialization and the prestige of the exact sciences to give heed to the other elements of human life but we’ve surely had enough experience by now of the limitations of both to spot the errors there. It’s not that these struggles weren’t without purpose or validity; it’s just that they cannot help us now. Modern times do indeed suffer from a huge maldistribution of capital, but that has nothing to do with foggy 19th century post-Hegelian metaphysics. Equal distribution of power comes way before equal distribution of wealth. The predominant working-class movement of Britain’s industrial heyday was Chartism before it was socialism, the simple struggle to be enfranchised. That priority was right. Either you’re a citizen, or you’re a subject, a slave.

Try asking a Syrian or a Yemeni refugee if economics trump politics, and if their most immediate concern is a redistribution of wealth. Might matters much more than money. It was Mao Tse-tung who said that power grows out of the barrel of a gun. No matter how false, partial and misunderstood that famous comment is, one thing it absolutely is not is an argument for the “withering away of the state” and the irrelevance of armed force. Economics does matter: No healthy democracy can survive without some mechanism to counter the inevitable accumulation of wealth in the hands of the wealthiest. But economics cannot provide a legitimate basis for sovereignty and justice, whether in plutocracy or in dictatorship of the proletariat. The property franchise was rightly seen as the most glaring offence of the British oligarchy prior to 1914. Equality before the law was a dead letter in a country that disenfranchised the majority of its citizens.

Economics has enjoyed primacy purely because it provided the vehicle or pretext for that most completely, entirely, exclusively political phenomenon: an ideology. There is plenty of room for progressive versus reactionary beliefs and parties in the modern political landscape, except that they make zero sense if they are constructed on some faceoff between Capital versus Labour. That’s as irrelevant and exploded as a division between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. As Hannah Arendt wrote, “race-thinking had been one of the many free opinions which, within the general framework of liberalism, argued and fought each other to win the consent of public opinion. Only a few of them became full-fledged ideologies, that is, systems based upon a single opinion that proved strong enough to attract and persuade a majority of people, and broad enough to lead them through the various experiences and situations of an average modern life. For an ideology differs from a simple opinion in that it claims to possess either the key to history, or the solution for all the ‘riddles of the universe,’ or the intimate knowledge of the hidden universal laws which are supposed to rule nature and man. Few ideologies have won enough prominence to survive the hard competitive struggle of persuasion, and only two have come out on top and essentially defeated all others: the ideology which interprets history as an economic struggle of classes, and the other that interprets history as a natural fight of races… not only intellectuals but great masses of people will no longer accept a presentation of past or present facts that is not in agreement with either of these views.” The 20th century proved that both are fake. Neither had the keys to history, or the solution to all the riddles of the universe. Economics is an important subject for the state and domain for government action, like many others in a state and a society, but it absolutely cannot provide the basis for legitimate sovereignty. The only legitimate as well as the only practical foundation for sovereignty is the free consent of the governed over the full area of the operation of a government. A state is the embodiment and articulation of that consent.

A state is not an expression of an individual or a general will, whether the will of a people or of some Hegelian geist. It is exactly an embodiment of the relinquishment of will, of the surrender of part of your individual volition, to be diffused and incorporated into institutions and codes of law. Constitutions and institutions exist precisely to balance out and arbitrate the chaos of individual wills, and to ensure the longevity and continuity of a community. A state’s legitimacy lies in the mediatization or delegation of this portion of discrete personal wills. Obviously, relinquishment like this is one of the easiest things to abuse in the world – King Lear is a warning to more of us than just kings – which is why the institutions needed to mediate it have to be held to such a high standard of accountability. The trust invested in them is immense. And the more states become expressions of will, the more they become despotisms or dictatorships. The more they ignore or override their own constitutions and institutions, the less legitimate they become, because they revert to exactly what a state was designed to prevent. There is no individual or general will that can challenge the legitimacy of institutions: they can be legitimately reformed or rebuilt by the same governments that they embody, as part of the state’s natural organic processes, but to challenge or supplant them from outside purely on the grounds that this is an expression of individual or general will is far beyond legitimacy. Margaret Thatcher was the one to pinpoint the referendum as “a device of dictators and demagogues” entirely because it overrode legitimate institutional and constitutional constraints under the colour of the general will. But the general will is not the expression of a democratic state, but its annihilation. No wonder today’s demagogues are so keen to seize on referendums.

As for the individual will, of the private person or the dictator, that is no more sovereign than the spinning jenny or Babbage’s difference engine. The individual, individuated, self-conscious personality is not man in a state of nature, but a highly sophisticated, delicate, cosseted product of millions of years of biological and social evolution. It may be one of the greatest achievements of such a process, but it is absolutely not foundational and prior to the incredibly complex institutions and social traditions that were required to enable it to come into being. A reasoning entity could have existed at any point during or before the evolution of Homo sapiens; a Rousseau, a Hamsun or a Raskolnikov could only have existed when they did. Men were born citizens since Antiquity; it took the Enlightenment to create the State of Nature.

If anyone needs a mathematical proof of democracy, that it is the only legitimate form of government, it is this: the Church-Turing thesis requires that any abstracted computing machine – meaning, any reasoning entity – must sooner or later be able to work through any and all reasoning problems. Mathematically, there can be no difference in kind between the reasoning capacity of any reasoning entity. There may be differences in degree, in the time or resources available to the entity to work through those problems, but those are absolutely arbitrary, not fundamental. All thinking beings are essentially the same. Given enough time and power, a pocket calculator’s innards, can, must be able to, work through any program for a supercomputer. No thinking being has an intrinsically higher competence that justifies it per se deciding on behalf of any other thinking being; any differences are local, historical incidentals. There can be plenty of good reasons for those incidentals, but none of them can yield the kind of in rerum natura justification required of sovereignty.

That principle of sovereignty also enshrines the greatest good of the greatest number as the guiding principle of policy. The same kind of Darwinian pseudoscience that fed into Marxism and social Darwinism has now got a fresh insight to contribute a couple of centuries later: cooperation means survival. Competition means extinction. Game theory analysis of evolutionary processes demonstrates exhaustively that the optimum survival strategy is the Golden Rule. Do as you would be done by. Do not do unto others what you would not have done to yourself. The strategy that provides initial cooperation rather than confrontation delivers the best chances for survival of all concerned. A conflict-first strategy drives everyone eventually to extinction, victor and victim alike. And it’s worth remembering that modern evolutionary theory postulates evolutionary processes as abstract mathematical algorithms, which happen to work particularly well in a biological context, but can equally well apply in economics, politics, etc. The same game theory applies across all. If Darwin didn’t have the mathematical and conceptual tools available for him to see that, then it’s no excuse for his self-styled inheritors to remain 150 years behind the times. The nationalist demagogues who claim some kind of Darwinian conflict of civilizations as the justification for their abandonment of democratic values are appealing to arguments that say they will exterminate us all.

Against the bigotry and entitlement, there is the cold mathematical game-theoretical fact that the greatest good really is for the greatest number, that the optimum survival strategy is always the win : win, and that if you pursue a zero : sum game, you are always going to end up, sooner or later, as the zero. There is only reason or force, democracy or fascism. Either a state is governed with equal regard for the rational capabilities of all its citizens, or it is controlled by, and for, the rulers who have appropriated its governing apparatus. And that equal regard does not stop at borders.

Globalization was a technological and practical fact long before it became a bogey-word for those sections of the Left whose goals are still linked to a 19th-century conception of the nation-state and state power. National governments cannot defend and protect workers, any more than they can protect their own borders and interests against predatory superstates. The boundaries of nations are no longer sufficient expressions of the frontiers of common interests. We are all far too close together now to duck the consequences when we affect others. There is multilateralism, or suicide by proxy. There is no survival unit smaller than the whole human race. There is no conceivable subset of humanity that is going to win out, or even be able to preserve the ecosystem that sustains it, while maintaining the fiction that we can play a zero-sum game and win. We have already gone up a level too high for that, despite the protests of those for whom the air is too rarefied up here. There is no more Capital and Labour; only Nationalism and Internationalism. If the left needs a new progressive project to replace the equal distribution of wealth, how about this: Justice and survival. It’s about time we got back to what used to be the rallying cry of the Left, the Internationale: United Human Race.

Paul StJohn Mackintosh, December 2019

A review of The Boughs Withered (When I Told Them My Dreams), by Maura McHugh

Irish short story and comic book writer and critic Maura McHugh has appeared in so many venues, including horror and weird fiction bastion Black Static and prestige anthologies like Joe S. Pulver’s Cassilda’s Song, that it comes as something of a surprise to learn that this is her first story collection. But so it is, spanning some 15 years of work, with 20 dark and weird tales, 4 of them original to this volume. With a title cheekily adapted from a verse of W.B. Yeats, a cover design by the ever-inspiring Daniele Serra, and the usual high production values of NewCon Press, The Boughs Withered (When I Told Them My Dreams) is an attractive enough package on the outside. What’s it like on the inside?

I’m glad to be able to report that The Boughs Withered is refreshingly diverse, varied in tone, diction, setting and even genre niche, and more imaginatively rich and highly coloured than many contemporary debut weird and dark fiction collections. There’s a snap to the dialogue and an engaging narrative pulse best captured in stories like “Spooky Girl” and “The Gift of the Sea.” It’s typical of Maura McHugh’s writing that the latter story manages to marry modern post-GFC Ireland with the spirit of Celtic mythology seamlessly. I don’t know if this is some kind of Flann O’Brien Irish gift to speak in many tongues, but it certainly makes for some highly enjoyable reading. The author commands a whole gamut of styles, and hardly ever leaves you feeling that her wordplay is wasted or overwrought. The settings also range from the Russia of legend to modern New York, with Ireland taking a leading but by no means an exclusive role, and some of that ranging afield has clearly been pivotal to her development as a writer, as she explains in her Afterword. She may write to “intuit the overlooked people who have been silenced,” but this is by no means her only concern. One of her most Irish historical stories, “Home,” is also one where cosmic horror slips into the picture, as it does in “The Diet.” Then again, at least one other story, “The Hanging Tree,” is “almost not supernatural at all” – but still very unsettling.

I don’t know what kind of expectations you might come to this book with, but chances are you’ll find them transcended. There’s infinite enough variety in it to upset anyone’s preconceptions. You’ll be spooked, but you’ll also be thoroughly entertained. That’s a far more important thing than is sometimes realized, and far rarer too. Maura McHugh brings it off in style. The Boughs Withered is a book you’re likely to come back to again and again just for the sheer pleasure of reading it. Now how uncommon, and how important, is that?

[Top]