Nationalism and Internationalism

Friday the 13th, and the Fates are laughing. Talk about bad timing. The most divisive, damaging UK election in decades yields its results on the most inauspicious day. Only a figure as tone-deaf to irony as to honesty and decency could have picked such a date. Who the gods would destroy…

Yes, there were signs of hope, when both Scotland and Northern Ireland elected progressive nationalist majorities. Yet were they beneficiaries of exactly the same forces that had mortally damaged the United Kingdom as a whole? Is one nationalism bad, and the other nationalisms good? Are nationalisms acceptable when they support progressive, left-leaning policies?

There’s one obvious lesson, which is that nationalism is a recipe for disintegration. There are few modern nation-states that are truly homogeneous enough to embrace chauvinist identity politics without risking internal fragmentation. Demagogues may seek to profit from that fragmentation, but it’s unlikely to do the nation-state in question much good. The so-called march of populism has mostly involved the manufacture of internal resentment of one part of the population against another as much as it has involved any genuine popularity. Demagogues are just becoming more ruthless about playing internal divide-and-rule, at whatever cost to their countries. Unfortunately, nationalism gives them every basis for doing just that.

From the former Yugoslavia to the current soon-to-be-disunited-Kingdom, it’s self-evident that nationalism within the nation-state on the model we’ve inherited from the 19th century destroys states, just as pan-Germanism destroyed the Austro-Hungarian Empire. There never was a “Great Britain” that wasn’t already a British Empire, and there never was a “British” nation that didn’t incorporate a diverse mix of traditional polities, ethnic stocks and religious traditions. The United Kingdom’s name is a great deal more honest than any attempt to pass it off as an ethnically distinct nation: it is a monarchical government that has united, sometimes by legal means but mostly by force, a great many lesser entities under its sway. Even before the modern, belated absorption of post-colonial immigrant populations as some kind of recompense and acceptance of its imperial legacy, “Great Britain” incorporated numerous different languages, ethnic sub-groups, and conflicting legal and religious traditions. Anyone calling it one nation is assuming a lot, and usually with an agenda. Try asking Chechens or Kurds or Tibetans if the modern nation-state is a sufficient basis for sovereignty.

The nation-state was not even the highest power in the supposed golden age of nation-states: it was simply a historic pretext or springboard for the acquisition of multiracial, multiethnic, polyglot empires, which have been the true Great Powers from ancient Persia and Peru on down. Once things had moved on from the march of Christendom to the Nation in Arms, the nation-state became the machinery for agglomerating and subjugating nations. Yet that national basis for conquest, competition and expansion put a time bomb at the core of the nation-state. The contradiction between the idea, or inherited tradition or myth, of a nation, and the realities of state power, is the kind that torments a mind devoted to the myth of nationhood to near insanity – it’s only resolvable in the end by the typically fascist rejection of thinking and critical analysis, and expiation through destructive and suicidal aggression.

There never was a Great British nation. Great Britain was a multinational empire from Day One: frequently at war with itself, always mixed and heterogenous. Nostalgia for greatness based on that kind of empire is obviously, insanely, at odds with nationalist enthusiasm for a sovereign British nation-state. A “Great” Britain that gives way to nationalism will find itself both split apart and ground between the far larger continental powers that are truly able to project geopolitical strength – on a level that one slice of the British population evidently still wishes they could, but can’t. You can count on the fingers of more than one hand the number of Chinese provinces whose individual population now exceeds that of the entire UK. Britain can only pander to such powers – exactly what it’s been doing since the Second World War, towards America.

Any attempt to recover national greatness is therefore blindly, insanely self-contradictory and destructive. And needless to say, the atavistic tribalism of collective emotions whipped up under the guise of nationhood makes a pretty poor mix with the apparatus of states. The adulation of nationhood was almost certain to transform nationalist states into killing machines on a massive scale, because any contradiction between the power of the state and the felt greatness of the nation had to be suppressed and eliminated, which ultimately meant exterminating the subject peoples – just as Nazi Germany did in the conquered territories of Eastern Europe. Napoleon’s Empire, the military realisation of the Nation in Arms, could only truly accept citizenship for the French and subjugation for the rest.

The nation-state does present one seductive feature for a certain section of the population: The abdication of citizenship. Weariness with the entire political process has been one of the hallmarks of the Brexit “debate,” and it’s all too easy to see where this can end. It’s been well said that fascism is not the people’s abandonment of democracy, but their abandonment of politics. They simply want to be the passive objects of government, not active, thinking participants as citizens. A prime minister who hid in a fridge was the perfect figurehead for what happened: the election of the xenophobia/selfishness/irrendentism/sloth that dare not speak its name. It was an election where voters really did not want to know, or be reminded of, or face up to, or be held to account for, let alone be shamed by, what they were voting for. An uncounted number were probably voting just for the opportunity to forget and give over the responsibility of thinking for a while. It looks like another of those English fits of absence of mind like the one where we acquired the enormous moral burden of the British Empire: a concerted effort of the left hand not to know what the right hand was doing. For an era stuffed with people trying to forget that their actions had consequences, it was the perfect poll.

Given the values on show, that’s hardly surprising. Only a few, more or less unhinged, right-wing figures – usually ideologues rather than practising politicians – actually admit to valuing and endorsing cruelty, bigotry, selfishness, and aggression for their own sake and on their own terms. Far more voters like to get the benefits without admitting the nature or the consequences of what they supported. That arch-priest of “the art of lying,” Adolf Hitler, preached the power of the Big Lie to overwhelm the judgment and discrimination of small minds, but it’s easy for small minds to play small tricks of moral sleight of hand to cheat their own consciences with, especially when no one is holding them up to judgment. (Small minds meaning uneducated or unexercised minds unable or unwilling to judge or evaluate.) This also neatly allows them to evade moral responsibility for their actions.

Even the Labour Party embraced the tactic. Having played Tory-lite in the Blairite era to provide a less repugnant version of pre-Crisis bonanza capitalism, it plugged the same tactic with Brexit, and tried to provide a more fudged, digestible version of the same prejudices and insularity. If the UK Labour Party couldn’t fight the Tory narrative that Polish plumbers and other immigrants were to blame for the woes of the English working class, then what legitimate claim did it have to be a party of the international labour movement? How shamefully far the British labour movement has fallen from the days when its heroes marched off to fight the Fascists in Spain.

Did the British working class have just cause to embrace nationalism to defend itself against globalization and job-stealing immigration? That debate falls down on the basis that it’s the modern Conservative, populist Big Lie. The myth left fact behind long ago. I don’t see much need here for a moral panic about the dangers of the Internet and fake news either: ever since the earliest approximations to a mass media, from the pulpits of Paris in 1572 to the Vienna of Karl Kraus’s “destruction of the world by black magic,” people have always followed what they wanted to hear. Certain aggressive outliers were more adroit and ruthless in mastering the new media, that’s all, just as highly motivated outsiders always have been. And they had material ready to hand in the form of fear and insecurity, the dry tinder of nationalism.

Nationalism is a collective expression of individual paranoia, facilitated by exactly the kind of fear and insecurity that propagate paranoia on the individual level. A demagogue’s first goal is to create paranoia, because fears overwhelm facts. Paranoia is delusional by definition; it also is one of the easiest abberant pathologies to foster and create on a mass level. Ignorance fuels suspicion, suspicion fuels paranoia, paranoia fuels fascism. And fascism is always going to be the totalitarianism of the stupid, because it appeals to the kind of insecure nature which views discrimination, thought, analysis, as a direct threat, to the kind of undifferentiated, syncretic identity that they cling to. You can see a whole lot of what Gerard Manley Hopkins once described as: “what came in with Kingsley and the Broad Church school, a way of talking (and making his people talk) with the air and spirit of a man bouncing up from table with his mouth full of bread and cheese and saying that he meant to stand no blasted nonsense.”

The Labour Party certainly had very few facts and arguments to hand to counter the nationalism of 2019 apart from those that it stole from the Conservatives. On the critical demographic and social divisions in England prior to the 2019 election – town versus country, young versus old, educated versus undereducated, internationalist versus nationalist – Labour had nothing to offer. Rich versus poor? Fine, except that left-wing conspiracy theorists were reduced to seeing the entire Leave : Remain debate solely in terms of two conflicting conspiracies of the rich.

Selective preference for any particular group, party or faction or class within a society, however disadvantaged, is the easiest thing to manipulate in the world, and is also the easiest thing to turn into chauvinist hostility when transferring to a different context. Robespierre’s sans-culottes were the cannon fodder for Napoleon’s armies. Class war is dead. Not because there are no disadvantaged classes, but because the only winner from such a war is the strongest warlord. A society built on the sovereignty of all has to work for the benefit of all; neither the rich, nor the insulted and injured. No state or community is perfect, and the balancing out of different claims is exactly what a state or society is about. But none can claim that any part enjoys preference or precedence by right – for reasons I’ll go into below.

Hating the rich is a fine and honourable pursuit but it is no substitute for freedom. and it takes no great perspicacity to see that the left has pivoted way over towards the Equality leg of the Liberty/Equality/Fraternity trinity at the expense of the other two, and worse, rewritten that Equality into primarily economic terms, not political terms. The 19th-century socialists may have been too in awe of industrialization and the prestige of the exact sciences to give heed to the other elements of human life but we’ve surely had enough experience by now of the limitations of both to spot the errors there. It’s not that these struggles weren’t without purpose or validity; it’s just that they cannot help us now. Modern times do indeed suffer from a huge maldistribution of capital, but that has nothing to do with foggy 19th century post-Hegelian metaphysics. Equal distribution of power comes way before equal distribution of wealth. The predominant working-class movement of Britain’s industrial heyday was Chartism before it was socialism, the simple struggle to be enfranchised. That priority was right. Either you’re a citizen, or you’re a subject, a slave.

Try asking a Syrian or a Yemeni refugee if economics trump politics, and if their most immediate concern is a redistribution of wealth. Might matters much more than money. It was Mao Tse-tung who said that power grows out of the barrel of a gun. No matter how false, partial and misunderstood that famous comment is, one thing it absolutely is not is an argument for the “withering away of the state” and the irrelevance of armed force. Economics does matter: No healthy democracy can survive without some mechanism to counter the inevitable accumulation of wealth in the hands of the wealthiest. But economics cannot provide a legitimate basis for sovereignty and justice, whether in plutocracy or in dictatorship of the proletariat. The property franchise was rightly seen as the most glaring offence of the British oligarchy prior to 1914. Equality before the law was a dead letter in a country that disenfranchised the majority of its citizens.

Economics has enjoyed primacy purely because it provided the vehicle or pretext for that most completely, entirely, exclusively political phenomenon: an ideology. There is plenty of room for progressive versus reactionary beliefs and parties in the modern political landscape, except that they make zero sense if they are constructed on some faceoff between Capital versus Labour. That’s as irrelevant and exploded as a division between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. As Hannah Arendt wrote, “race-thinking had been one of the many free opinions which, within the general framework of liberalism, argued and fought each other to win the consent of public opinion. Only a few of them became full-fledged ideologies, that is, systems based upon a single opinion that proved strong enough to attract and persuade a majority of people, and broad enough to lead them through the various experiences and situations of an average modern life. For an ideology differs from a simple opinion in that it claims to possess either the key to history, or the solution for all the ‘riddles of the universe,’ or the intimate knowledge of the hidden universal laws which are supposed to rule nature and man. Few ideologies have won enough prominence to survive the hard competitive struggle of persuasion, and only two have come out on top and essentially defeated all others: the ideology which interprets history as an economic struggle of classes, and the other that interprets history as a natural fight of races… not only intellectuals but great masses of people will no longer accept a presentation of past or present facts that is not in agreement with either of these views.” The 20th century proved that both are fake. Neither had the keys to history, or the solution to all the riddles of the universe. Economics is an important subject for the state and domain for government action, like many others in a state and a society, but it absolutely cannot provide the basis for legitimate sovereignty. The only legitimate as well as the only practical foundation for sovereignty is the free consent of the governed over the full area of the operation of a government. A state is the embodiment and articulation of that consent.

A state is not an expression of an individual or a general will, whether the will of a people or of some Hegelian geist. It is exactly an embodiment of the relinquishment of will, of the surrender of part of your individual volition, to be diffused and incorporated into institutions and codes of law. Constitutions and institutions exist precisely to balance out and arbitrate the chaos of individual wills, and to ensure the longevity and continuity of a community. A state’s legitimacy lies in the mediatization or delegation of this portion of discrete personal wills. Obviously, relinquishment like this is one of the easiest things to abuse in the world – King Lear is a warning to more of us than just kings – which is why the institutions needed to mediate it have to be held to such a high standard of accountability. The trust invested in them is immense. And the more states become expressions of will, the more they become despotisms or dictatorships. The more they ignore or override their own constitutions and institutions, the less legitimate they become, because they revert to exactly what a state was designed to prevent. There is no individual or general will that can challenge the legitimacy of institutions: they can be legitimately reformed or rebuilt by the same governments that they embody, as part of the state’s natural organic processes, but to challenge or supplant them from outside purely on the grounds that this is an expression of individual or general will is far beyond legitimacy. Margaret Thatcher was the one to pinpoint the referendum as “a device of dictators and demagogues” entirely because it overrode legitimate institutional and constitutional constraints under the colour of the general will. But the general will is not the expression of a democratic state, but its annihilation. No wonder today’s demagogues are so keen to seize on referendums.

As for the individual will, of the private person or the dictator, that is no more sovereign than the spinning jenny or Babbage’s difference engine. The individual, individuated, self-conscious personality is not man in a state of nature, but a highly sophisticated, delicate, cosseted product of millions of years of biological and social evolution. It may be one of the greatest achievements of such a process, but it is absolutely not foundational and prior to the incredibly complex institutions and social traditions that were required to enable it to come into being. A reasoning entity could have existed at any point during or before the evolution of Homo sapiens; a Rousseau, a Hamsun or a Raskolnikov could only have existed when they did. Men were born citizens since Antiquity; it took the Enlightenment to create the State of Nature.

If anyone needs a mathematical proof of democracy, that it is the only legitimate form of government, it is this: the Church-Turing thesis requires that any abstracted computing machine – meaning, any reasoning entity – must sooner or later be able to work through any and all reasoning problems. Mathematically, there can be no difference in kind between the reasoning capacity of any reasoning entity. There may be differences in degree, in the time or resources available to the entity to work through those problems, but those are absolutely arbitrary, not fundamental. All thinking beings are essentially the same. Given enough time and power, a pocket calculator’s innards, can, must be able to, work through any program for a supercomputer. No thinking being has an intrinsically higher competence that justifies it per se deciding on behalf of any other thinking being; any differences are local, historical incidentals. There can be plenty of good reasons for those incidentals, but none of them can yield the kind of in rerum natura justification required of sovereignty.

That principle of sovereignty also enshrines the greatest good of the greatest number as the guiding principle of policy. The same kind of Darwinian pseudoscience that fed into Marxism and social Darwinism has now got a fresh insight to contribute a couple of centuries later: cooperation means survival. Competition means extinction. Game theory analysis of evolutionary processes demonstrates exhaustively that the optimum survival strategy is the Golden Rule. Do as you would be done by. Do not do unto others what you would not have done to yourself. The strategy that provides initial cooperation rather than confrontation delivers the best chances for survival of all concerned. A conflict-first strategy drives everyone eventually to extinction, victor and victim alike. And it’s worth remembering that modern evolutionary theory postulates evolutionary processes as abstract mathematical algorithms, which happen to work particularly well in a biological context, but can equally well apply in economics, politics, etc. The same game theory applies across all. If Darwin didn’t have the mathematical and conceptual tools available for him to see that, then it’s no excuse for his self-styled inheritors to remain 150 years behind the times. The nationalist demagogues who claim some kind of Darwinian conflict of civilizations as the justification for their abandonment of democratic values are appealing to arguments that say they will exterminate us all.

Against the bigotry and entitlement, there is the cold mathematical game-theoretical fact that the greatest good really is for the greatest number, that the optimum survival strategy is always the win : win, and that if you pursue a zero : sum game, you are always going to end up, sooner or later, as the zero. There is only reason or force, democracy or fascism. Either a state is governed with equal regard for the rational capabilities of all its citizens, or it is controlled by, and for, the rulers who have appropriated its governing apparatus. And that equal regard does not stop at borders.

Globalization was a technological and practical fact long before it became a bogey-word for those sections of the Left whose goals are still linked to a 19th-century conception of the nation-state and state power. National governments cannot defend and protect workers, any more than they can protect their own borders and interests against predatory superstates. The boundaries of nations are no longer sufficient expressions of the frontiers of common interests. We are all far too close together now to duck the consequences when we affect others. There is multilateralism, or suicide by proxy. There is no survival unit smaller than the whole human race. There is no conceivable subset of humanity that is going to win out, or even be able to preserve the ecosystem that sustains it, while maintaining the fiction that we can play a zero-sum game and win. We have already gone up a level too high for that, despite the protests of those for whom the air is too rarefied up here. There is no more Capital and Labour; only Nationalism and Internationalism. If the left needs a new progressive project to replace the equal distribution of wealth, how about this: Justice and survival. It’s about time we got back to what used to be the rallying cry of the Left, the Internationale: United Human Race.

Paul StJohn Mackintosh, December 2019

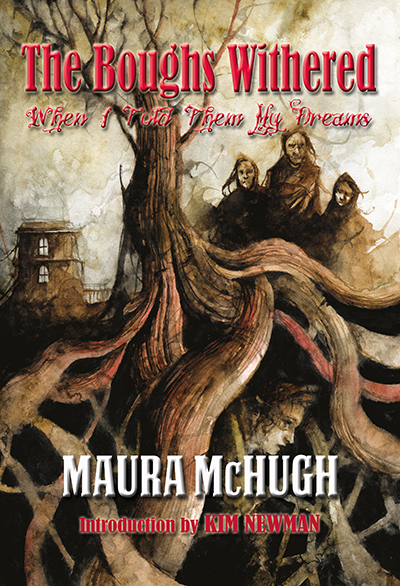

A review of The Boughs Withered (When I Told Them My Dreams), by Maura McHugh

Irish short story and comic book writer and critic Maura McHugh has appeared in so many venues, including horror and weird fiction bastion Black Static and prestige anthologies like Joe S. Pulver’s Cassilda’s Song, that it comes as something of a surprise to learn that this is her first story collection. But so it is, spanning some 15 years of work, with 20 dark and weird tales, 4 of them original to this volume. With a title cheekily adapted from a verse of W.B. Yeats, a cover design by the ever-inspiring Daniele Serra, and the usual high production values of NewCon Press, The Boughs Withered (When I Told Them My Dreams) is an attractive enough package on the outside. What’s it like on the inside?

I’m glad to be able to report that The Boughs Withered is refreshingly diverse, varied in tone, diction, setting and even genre niche, and more imaginatively rich and highly coloured than many contemporary debut weird and dark fiction collections. There’s a snap to the dialogue and an engaging narrative pulse best captured in stories like “Spooky Girl” and “The Gift of the Sea.” It’s typical of Maura McHugh’s writing that the latter story manages to marry modern post-GFC Ireland with the spirit of Celtic mythology seamlessly. I don’t know if this is some kind of Flann O’Brien Irish gift to speak in many tongues, but it certainly makes for some highly enjoyable reading. The author commands a whole gamut of styles, and hardly ever leaves you feeling that her wordplay is wasted or overwrought. The settings also range from the Russia of legend to modern New York, with Ireland taking a leading but by no means an exclusive role, and some of that ranging afield has clearly been pivotal to her development as a writer, as she explains in her Afterword. She may write to “intuit the overlooked people who have been silenced,” but this is by no means her only concern. One of her most Irish historical stories, “Home,” is also one where cosmic horror slips into the picture, as it does in “The Diet.” Then again, at least one other story, “The Hanging Tree,” is “almost not supernatural at all” – but still very unsettling.

I don’t know what kind of expectations you might come to this book with, but chances are you’ll find them transcended. There’s infinite enough variety in it to upset anyone’s preconceptions. You’ll be spooked, but you’ll also be thoroughly entertained. That’s a far more important thing than is sometimes realized, and far rarer too. Maura McHugh brings it off in style. The Boughs Withered is a book you’re likely to come back to again and again just for the sheer pleasure of reading it. Now how uncommon, and how important, is that?

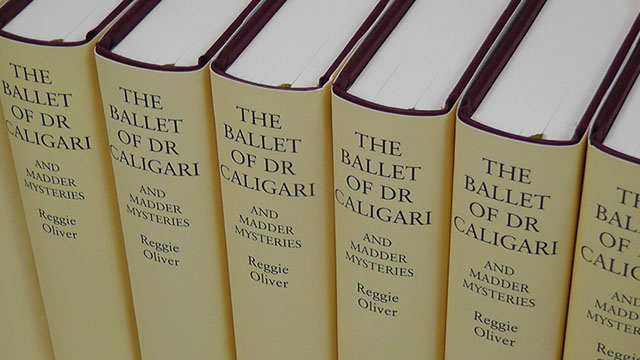

[Top]A review of The Ballet of Dr Caligari and Madder Mysteries, by Reggie Oliver

Reggie Oliver has become an institution in modern British horror, producing volume after volume of finely crafted stories in the best tradition of weird fiction and ghost stories. Thanks to him, any reader who enjoys tales of this kind has a hugely enlarged bill of fare to sample – this is his eighth collection, containing thirteen stories. It’s produced to the usual superlative standard of Tartarus Press collectible editions, although for anyone who can’t afford the very high, but completely justified, hardback price, there are equally high-quality ebook copies in various formats available from Tartarus, as well as paperback. So how mad, and how mysterious, is it?

A couple of the stories here are straight recreations or completions of the work of M.R. James. “ The Game of Bear ” completes an unfinished story by James in exactly the kind of manner a Jamesian fan could expect, with a suitably ghastly conclusion. “The Devil’s Funeral” is a historical ghost story in the epistolary style mastered by James, concerning an appropriately folklorish local tradition and a haunted clergyman. If you come to Reggie Oliver’s work looking for such pleasures, you’ll find them in plenty. Jamesian antiquarian ghost stories are only part of his range, though. There are other stories here with a strong antiquarian and historical dimension – “A Donkey at the Mysteries,” “The Endless Corridor,” “The Vampyre Trap,” “Lady with a Rose” – but they are mostly either framed in a much more contemporary context, or have a very different take on the narrative. “The Vampyre Trap,” for example, is more of a historical detective mystery than a ghost story, though with a strong gothic dimension. And the historical and scholarly trappings are often more in the spirit of that other great British master of the weird tale, Robert Aickman, with all the appropriately surreal and psychologically ambiguous flavour. “The Ballet of Dr Caligari” itself, with its disturbing evocation of a demonically influential stage piece, or “The Final Stage,” a nightmare dream journey through fragments of identity in masks and mirrors, smack of quintessential Aickman. Reggie Oliver is far beyond just a follower of the Jamesian tradition. He does have many styles and registers, from the genially satirical to the historical pastiche, but of all the dark and weird tales I’ve read, at least one of his stories sticks in my mind as one of the few that has genuinely scared and disturbed me, and in this jaded age, that’s saying something.

The classic English ghost story, then is very much alive in Reggie Oliver’s hands. It’s also far beyond what it appears to be on the surface, even if those surface aspects will be the chief attraction for many readers. A supremely enjoyable volume, from a writer who seems to go from strength to strength.

[Top]Paranoia and the Genesis of Fascism

Reflections after reading Robert O. Paxton’s The Anatomy of Fascism

Robert O. Paxton’s The Anatomy of Fascism does a great job of anatomizing fascism, without fully explaining why it is the way it is. He spotlights fascism’s “mobilizing passions” – often too incoherent and anti-rational to be called ideas – as the chief anatomical markers that distinguish it: a sense of overwhelming, unprecedented crisis; group primacy beyond any individual right; perceived victimhood; dread of group contamination and decline; communal purification and reintegration, usually forcible; personal authority of male leaders; veneration of the leader’s instincts above reason; veneration of violence and volition for their own sake; and a Darwinian entitlement to dominate and crush others. He stresses consistently that actual fascism is not an ideology but a phenomenon more like a disease that afflicts ailing democracies. What ideas and ideologies fascism does develop along the way are usually there as attempts to emulate more coherent creeds like Marxism, and are usually ridiculous monuments to fascist anti-intellectualism. But if fascism doesn’t have a coherent ideology, it does have a character, characterized by those symptoms already listed above.

I think there’s a lot to be gained by attempting to deduce what forms fascism’s character. Paxton has done most of the work already on the formative influences, with way more depth than I can claim to, but there are elements, to my mind, that exceed his explanatory models – for instance, the adulation of violence for its own sake, and the sickening brutality of fully realized and radicalized fascism. Plus if we look more closely at the genesis of fascism, we may also be more able to pick it out when it doesn’t exhibit some of the superficial symptoms that we expect from our preconceptions. It’s not always about paramilitary thugs in uniform. (Paxton points out that – contrary to later fascist myth – both Mussolini and Hitler accidentally achieved some of the key moments of their careers in conventional respectable morning wear.) That kind of extrapolation may require a lot of speculation and argument rather than demonstration. The facts aren’t always to hand, especially for the here and now, and I’m going to resort to inference to bridge the gaps. Perhaps that’s too much of a reach for the conscientious historian compelled to back up all conclusions with firm data. All the same, I think it’s a reach worth taking, not least to get a handle on the present fascist phenomena that are busy shaping history right now.

To my mind, one of the most valuable guides to help explain the genesis of fascism is the pathology of paranoia. You can map the pathology of paranoia onto the formative conditions of fascism, point by point. Feelings of powerlessness and victimization, low social status and unstable social environment, a sense of helplessness at the mercy of external forces, persecutory delusions and false beliefs, over-suspicious hypervigilance, conspiracy theories: it’s all there. What’s more, paranoia on the individual level and fascism on the group level arise in the same social and economic conditions and from the same causes. It’s almost enough to characterize paranoia as a sociological rather than a psychological phenomenon. Plus, those prone to fascism in politics are that much more likely to be mentally unstable and manipulable as individuals – again, for the same reasons. For the would-be demagogue, that seems like a great guide for seeking out – or creating – the most extreme fascist support base. Sound like anyone you know?

Social and economic dislocation may go partway towards explaining the genesis of both paranoia and fascism, but they don’t explain everything, least of all the primacy given to the group that is one of the most glaring symptoms of fascism. Why this emphasis on the group, “superior to every right, whether individual or universal,” as Paxton puts it? He gives one purely pragmatic explanation: the justification of crushing any resistance or alternative centre of power facing a mass movement. But in my opinion, there’s more that underlies the emphasis on the group, stemming from the common roots of fascism and paranoia.

Group strength and solidarity is the basis for individual security and identity. At least, that’s how many groups, and many individuals, feel. Outside the abstract customary or rational structures of law and institutions, it’s the Us that supports and protects the vulnerable and often undifferentiated Me. Group strength and group uniformity are practically one and the same, to this way of thinking. The group’s identity is what constitutes and identifies the group in the first place; therefore, the stronger the group is, the more it will project and affirm its identity. (Conversely, some insecure souls may start to identify diversity and divisions within the group as signs of weakness and decay.) Especially insecure and fragile individual identities are going to seek validation and stability by overcompensatory assertion of the group identity. A paranoid group, or a group composed of individuals driven into paranoia, is likely to have exactly the same collective pathology as paranoia on the individual level.

Absent an actual, direct, real external threat to a group, but with a constant stressful sense of threat and debility, how is a group likely to respond? It’ll try to double down on cohesion, unity, and reinforcement of its identifying qualities as a group, however mythical or arbitrary those are. Common identity, cohesion is the only strength the group has. Almost always this is going to be through backward-looking atavism and a reversion to what are seen as earlier communal norms, in the face of the kind of incoherent complexities that appear to threaten and contaminate the group. Male-worship and machismo is one obvious example, often in overreaction to the economic powerlessness and loss of self-respect that fosters individual and collective paranoia. Haunted by fears of social, political and personal impotence, the fascist naturally overcompensates by idealizing machismo. Overcompensatory reinforcement of the primacy and authority of the group also ups the stakes for commitment to the universality and the supremacy of the group and its values. The more the group is exalted as the totem of all strength and security, the more the counter-claims, or even the existence, of any other group is an existential threat to be fought with all the fervour that stems from fear. For any sufficiently insecure group, the mere existence of other groups is a threat, whether it’s domestic minorities or external nationalities. They are an inherent contradiction that a group in its panic atavistic rush back to its mythical founding simplicity cannot abide.

What about the emphasis on violence and the will? I’m mentioning that now because they seem to me to be very much connected with this urge for a simpler, stronger, purer life that signifies the confused, anxious, incoherent paranoid personality casting around for sources of stability and self-reinforcement. Confusion and fear go hand in hand in fostering this mentality. Ignorance and poor education are natural progenitors of paranoia and fascism, because when you genuinely don’t know and/or can’t understand the forces shaping your life, you’re that much more likely to be afraid of them and to feel helpless in the face of them. You’re also that much more likely to seek simple, usually violent solutions when dealing with them. Partly it’s the release of rage and frustration, the urge to smash what thwarts you that you don’t understand. Partly it’s an attempt to redeem and pay back the felt humiliation of past life without pay, job, social security, pride and self-esteem, whatever. For anyone feeling persecuted, helpless and humiliated, violence is the natural response, especially in a situation where rational solutions no longer appear to work. It’s also the most alluring option for those to whom violence comes naturally. Fascist movements may get a boost from action-hungry groups already habituated to violence, hooked on violence and the adrenalin rush, like Hannah Arendt’s post-WWI “Front Generation,” but most unstable social environments are likely to throw these up anyway. This may have a nasty suggestive corollary in praxis, and in Karl Marx’s dictum that “the philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” In any event, once you feel threatened, you react violently. And fascism, like paranoia, depends on the principle that difference, unfamiliarity, contradiction, separateness, are not just threats, but the threat.

Projection and overcompensation come easy to anyone unschooled in reflection, objective thinking and self-analysis. That pretty much fits both the paranoid individual and the fascist group. Umberto Eco and many others have commented on the absolute antipathy of fascism to intellectual analysis: contemptuous anti-intellectualism masking desperate vulnerability to any truth test. It’s also likely to produce the kind of self-destructive death spiral Paxton has identified in terminal-stage fascism in Germany and Italy, where insanity piles on insanity as the reality principle is left ever farther behind. It also explains the kinds of fantastic megalomania cited by Hannah Arendt, where totalitarian leaders apparently acted in deliberate defiance of the facts, just to demonstrate that they could. Fascism is the Big Lie that paranoia’s little lie has grown into. There’s hardly any need to quote Joseph Goebbels on this, but as a tribute to his rare candour: “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it. The lie can be maintained only for such time as the State can shield the people from the political, economic and/or military consequences of the lie. It thus becomes vitally important for the State to use all of its powers to repress dissent, for the truth is the mortal enemy of the lie, and thus by extension, the truth is the greatest enemy of the State.” Truth is surely the greatest enemy of every populist government currently in office. No wonder they’re so anti-media.

I hope this helps allay a few fears and hesitations about dealing with fascists in the public sphere. Public will? Public insanity. Popular choice? Popular delusion and the madness of crowds. Why should you be at the mercy of behaviour and attitudes in politics that would be instant grounds for incarceration for a private individual? These people are sick – literally. No one defends the right of a delusional paranoiac to act out their paranoid delusions to the harm of others. No one has a right to expect anyone else to abide by their lie. Yet unscrupulous individuals and power groups have the tools to identify and mobilize masses by driving them mad. “Insanity in individuals is something rare – but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs it is the rule,” said Nietzsche. He probably meant more than literal, clinical insanity – but nonetheless, here is the actual clinical thing itself, acting en masse in politics, and being whipped up and into the polls by leaders and manipulators equally mad with the same affliction. You can see why Orwell declared that: “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.” And why he represented the state creed of Oceania as the same self-delusional solipsism that any paranoid is locked into.

Regardless of how far the rights of the individual or the group to deny reality extend in the political sphere, we know very well what happens in the social or legal sphere. Delusional psychopaths get certified as criminally insane and locked up. Delusional groups like the Heaven’s Gate cult, the People’s Gate cult or the Branch Davidians slaughter themselves, or others, or both, if the legal and medical authorities can’t shut them down first. In the political sphere, we have institutions and constitutions designed to protect us from such outbreaks. Are we to defer to the will of the lunatics if they do take over the asylum? Democracy depends on rational choice; it is premised on the people being rational actors. Any standard of legal autonomy, responsibility and accountability depends on that. It also provides a handy litmus test for the defenders of democracy: the moment you start to spread lies and deny reality, stoke fears and foster insanity, you cease to be a democrat and become a demagogue. And you lose all democratic legitimacy. Trump, Putin, Farage, Johnson, Orban, Salvini – they all qualify. They tick just about every box in Paxton’s list, even the violence box for some. Absolute adherence to the truth may be a high bar for any modern politician to meet, but it’s a minimally sufficient and necessary standard of democratic legitimacy. If you distort reality, you represent, not rational actors, but the insane.

Political norms like the will of the people as a corollary to individual liberty depend on sanity and rationality at the individual level: how come no one sees fit to apply that test at the public level, where insanity and irrationality can do far more harm? We certainly shouldn’t hesitate to act against collective insanity when we do see it, because that’s exactly what fascism is.

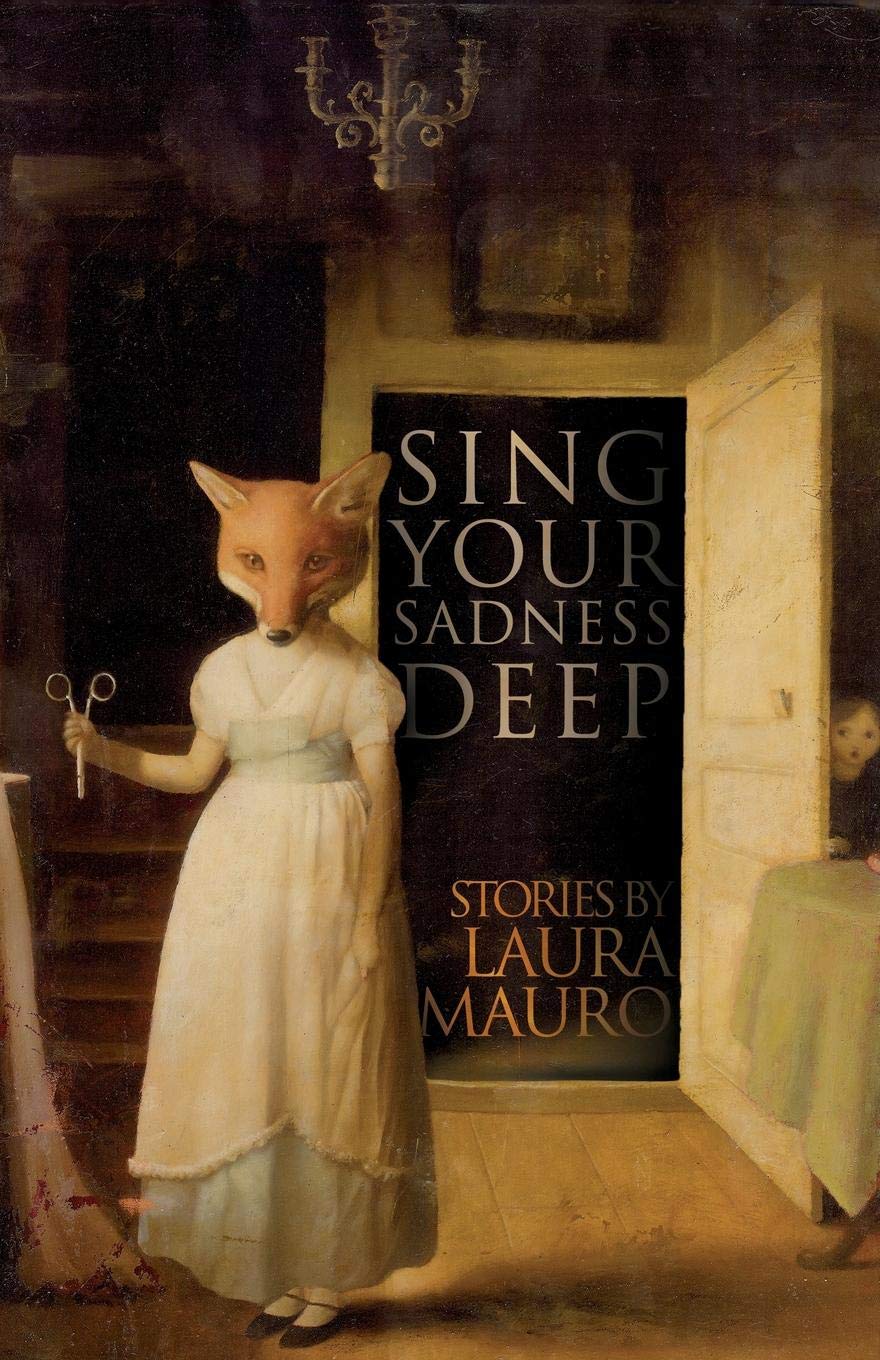

[Top]A review of Sing Your Sadness Deep, by Laura Mauro

Laura Mauro’s first collection delivers on the promise that has netted her a British Fantasy Award and a Shirley Jackson Award finalist placing, and its quality is so consistently high that I’m sure more awards must be on the way. The thirteen stories herein are at least that good, spanning her career from her first appearance in Undertow Publications’ Shadows & Tall Trees 4 in 2012 to date, in a book produced to Undertow’s usual superlative standards.

There’s an awful lot of toxic family dysfunction in this collection. Philip Larkin fans will be very glad to have “They fuck you up, your mum and dad” confirmed in spades. Not just mum and dad, but epileptic sister, bizarre homesquatting homunculus, birdboned acephalic foetus, foggy revenant father, guilty bloodstained mother, fish-skinned foundling, wooden changeling sibling, angelic adoptee, painsucking grandpa. Look at the cover illustration, so well suited to the contents, with the girl-child peering from behind the door at the fox-faced (mother?) figure in Jane Austen dress, scissors threateningly poised. That’s how distorted, surreal and mutagenic relations and relationships are in these tales. Almost always here the strangeness blossoms from the cracks and fault lines between people.

As that might suggest, the story premises here are resolutely weird, and very seldom what you’d expect. There’s a welcome diversity of setting and background, as well as of inspiration and narrative trope. Laura Mauro is a British weird fiction writer, but she doesn’t let that constrain her in the slightest. Story settings range far and wide, from suburbia to Siberia, Utah to Oulu, Brighton to Bothnia, the Isle of Wight to Ireland, Sussex to Sicily – all rendered in a spare, sinuous prose that weaves its way through the intricacies of the stories without pausing for self-indulgent ornamentation. I would be very interested to see where she goes from here, but I’m confident that it will be broader and even better – as far as that’s possible. British weird fiction is fertile indeed if it’s producing first growths like this bouquet of porcelain flowers of pain. Highly recommended.

[Top]A review of The Very Best of Caitlín R. Kiernan

With a writer like Caitlín R. Kiernan, a title like The Very Best of… is begging a lot. Where’s the ferociously parodic, deconstructive urban fantasy she writes under her Kathleen Tierney nom de guerre? Where’s the Delta Green-flavoured Lovecraftian technothrillers like Agents of Dreamland and Black Helicopters? Where’s her comic contribution to the Sandman mythos? In any collection from such an author, there’s always bound to be, not only favourite stories, but entire sub-genres missed out. I want to put in this quote to illustrate the point, because it’s the kind of thing you so rarely get to include in a review: “Brown University’s John Hay Library has established the Caitlín R. Kiernan Papers, spanning her full career thus far and including juvenilia, consisting of twenty-three linear feet of manuscript materials, including correspondence, journals, manuscripts, and publications, circa 1970-2017, in print, electronic, and web-based formats.” Count ‘em: twenty-three linear feet. It’s a brave editor or publisher who would dare try to encapsulate every facet of an author so various, and so prolific.

What this compilation does demonstrate is that Caitlín R. Kiernan is producing the very best of contemporary dark and weird fiction, regardless of whether or not that typifies her whole range. She not only has written more than nine-tenths of her contemporaries, she has also written substantially better than nine-tenths of them. She casually throws off metaphor and imagery in passing that would make any other writer’s career. Kiernan has a word horde as rich as Smaug’s, and a voice as mesmeric.

Part of her mastery of different genres and sub-genres is her unerring ear for the idioms, idiolects, speech communities, buzzwords, shibboleths, jargon, psychobabble, technobabble, Mythobabble of each side alley and cul-de-sac of imaginative literature. Her debt to 1890s decadent literature might have helped tune her ear for distinct prosodies, but even when it’s fully on view, as in “La Peau Verte,” it isn’t anything like as overblown and cloying as Angela Carter or Poppy Z. Brite. Kiernan’s frame of stylistic reference isn’t anything like that narrow, and she doesn’t wallow in overwrought prose like many self-declared decadent authors. She tosses in quotations and references from the whole gamut of literature that you’d ache to see more often in genre fiction, yet she keeps a sinew and thrust in her writing that nails all the glitter and sparkle of her stylistic brilliance firmly to the underlying contours of her narrative. Sometimes her more experimental pieces do tax the reader’s patience – I’m no fan of the unparagraphed construction of “Interstate Love Song (Murder Ballad No. 8)” for instance – but such excesses are rare, and generally tempered by a propulsive impetus, let alone a turn of phrase, that makes her fables unputdownable. “Houses under the Sea,” does dip into the deep waters of her best-known single work, The Drowning Girl: A Memoir, but that doesn’t render this collection any less a partial glimpse at best. And there’s that word again.

Kiernan has gone on record in the past to state that she’s “getting tired of telling people that I’m not a ‘horror’ writer. I’m getting tired of them not listening, or not believing.” It’s true that miscegenation and body horror are recurrent themes – steampunk prostheses, flesh sculptures, alien distortion/transcendence of normal humanity – frequently embodied in or espoused by mutated former lovers. Yet she typifies horror as “an emotion, and no one emotion will ever characterize my fiction.” She’s also said that “story bores me. Which is why critics complain it’s the weakest aspect of my work.” I don’t see any lack of story in these stories, though. I also suspect that Kiernan wouldn’t have been able to keep readers’ attention across such a huge volume of work unless she was able to keep them engaged through extended narratives with more than just jewelled individual sentences. She shares that characteristic gift of a really good short story writer of tieing off a section or a passage with a line that hooks you and leaves you gasping, aching to see what comes next. And if she has any uniformity of tonal range or register, it’s one that carries superbly well across genre after genre, from the folk horror of “A Child’s Guide to the Hollow Hills,” to the superb occult noir of “The Maltese Unicorn.” Not only would what she pulls off in that one story alone make another writer’s entire career, I’ve actually seen it happen.

In their introduction to The Weird, Ann and Jeff VanderMeer write that Kiernan has “become perhaps the best weird writer of her generation.” There’s only two parts to that statement I’d question: Only weird? And perhaps? Weird fiction as a genre, if it is a genre, should be grateful to be able to lay even partial or intermittent claim to her. Caitlín R. Kiernan is the fulfilment of every weird fiction pundit’s dream of a transgressive, inclusive, brutally contemporary author who brings all the territory’s sub-genres bang up to date while ditching their historical baggage – yet she effortlessly transcends such categories and limitations, just as she effortlessly transcends every genre she’s cared to touch down in. Even after successive World Fantasy Awards and Bram Stoker Awards, she’s still a writer who can’t be honoured and recognized enough. Words fail me. But they rarely if ever fail her.

[Top]A review of This House of Wounds, by Georgina Bruce

This first collection from Georgina Bruce, published by Michael Kelly’s weird emporium par excellence Undertow Publications, gathers 16 short stories, including the British Fantasy Award-winning story “White Rabbit,” which comes at the tail end of the book. This House of Wounds provides Georgina Bruce with the grounding in print she deserves to complement her presence in the British fantasy and weird fiction scene. It also consolidates Undertow’s standing as the go-to house for the modern weird renaissance, because if you have authors like this on your list, you absolutely epitomize the cutting edge of the field.

This House of Wounds is simply a gorgeous book, with ravishing cover art by Catrin Welz-Stein to complement the contents. Fairy-tale motifs abound – Red Queens, sorcerous crows, Princess Beasts, Woods Kings – yet they’re frequently jump-cut past the reader in fragmented, discontinuous, subjective glimpses, like a mystic marriage of Angela Carter with J.G. Ballard. And the beauty and glitter is frequently the sparkle of streams of blood or the shine of polished bone – the wounds are there, laid bare and held open by retractors for probing and examination. This absolutely is not horror per se, but it touches on horror territory persistently. As the author has said, “I don’t think it’s possible to write about reality without encountering horror imagery and themes,” and if the collection ever touches on the British tradition of fey whimsy, it’s with an ironic, lacerating, mirror-sharded claw.

With many of the stories running at ten pages or less in the 179-page Kindle edition, there’s almost a suggestion of prose poetry, as though Rimbaud had ingested a bizarre infusion of Poe, or Kafka had taken a whiff of some Nineties Decadent opiate. That’s not just a matter of concision and density either. Georgina Bruce’s prose frequently rises to glittering pinnacles of decorative baroque flourish, without breaking off from the solid architecture underneath. “Deep and slick and fast and moving in a fluid dance, a flow of her body through trees, a flick of coal glowing within her thighs, a ribbon of flame rising and fluttering.” It’s anything but pedestrian.

For such a short and strongly characterized book, though, there’s nonetheless a great deal of variety. There’s dystopian science fiction à la Philip K. Dick (“Wake Up, Phil”), psychological horror (“The Art Lovers”), and a diversity of style from stream of consciousness to straightforward narrative. This is almost always going to be the case in a first collection, but there’s a uniformity of achievement and skill that balances the variety of styles and treatments. Georgina Bruce has gathered many points of departure in this book that she could set out from to map out different areas of her range, and it’s going to be fascinating to see which and how many she explores. For the reader, it’s going to be a fascinating and rewarding journey.

This House of Wounds is simply a must-have. You can digest it at one sitting, yet you’ll find yourself coming back to it again and again. Buy it; read it: you won’t be disappointed.

[Top]