New short story

Yes, *another* new story – not connected to the wonderful new Norwegian horror film Thale, and begun well before it, but hats off to you, guys. This was actually inspired by a visit to Iceland with school way back. Now read on …

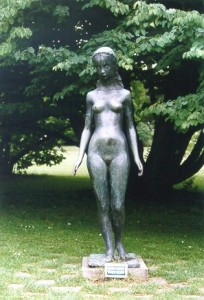

The Huldra

The ash fells were bleak as Ragnarok, friable pumice slopes scoured bare and grey by the abrasive wind that swept down off the ice-blue glacier. Green grass grew on the flanks of the crags, and a few sere patches of ground cover dotted the valley floor, but otherwise there was no variation in the charred landscape: bird, animal and human life were completely absent, and only the braided river scraping along its gravel bed distinguished it from the surface of the moon. One isolated outcrop, enthroned atop the valley wall,dominated the scene, a gigantic black demon squatting on its haunches, one claw resting across its knees, surveying its domain.

Adam Nielsen stepped back from the eyepiece of his laser theodolite to check the monumented benchmarks either side of the road ahead. The Icelanders in the road gang stood about drinking their coffee from aluminium flasks or watching him line up on the next stretch of unmetalled wheel ruts.

This leg of the route made for fairly perfunctory surveying: the valley floor was flat and level, with no sudden inclines. It was almost a two-dimensional landscape: the few distant verticals marking the limits of the flat scoria plains. His job at this stage was more to tease out the contours to keep the widened road clear of meltwater in the spring, when runoff from Myrdallsjokull and the skirts of Hekla sluiced down the rough gullies, washing the ash. He had few natural obstacles to avoid, and none manmade: here on the southern fringes of the Icelandic Highlands, there were no settlements, just the barren ash desert stretching away to the hills. The road improvement scheme was supposed to open up the interior and facilitate coast-to-coast communication, but Nielsen found it hard to imagine anyone choosing to live up here, unless they had a yen for the stark, austere grandeur of the place.

The smooth gradient across the nearside of the valley floor was obstructed by a single lonely rock about two metres high by four wide, perhaps a glacial erratic, with a dusting of rusty orange moss across its broad flat back. Squinting at the dark mass, Nielsen mentally weighed up the amount of blasting explosive needed to pulverize it.

“Better steer clear of that rock.”

Nielsen stood up and turned round. The foreman had come up behind him unnoticed, and was regarding him calmly.

“Why not?”

“It’s the huldra’s rock,” the foreman answered, shrugging as though that was all that needed to be said.

Huldra: he struggled for a moment to place the name. Some legendary forest witch, a seductress who slew her unsatisfactory conquests. He knew Icelanders were supposed to be a superstitious bunch, and still believe in tales of elves and so on, but even so this seemed a bit much.

“So you’re telling me that we should reroute the road hundreds of metres out of the way just to avoid that rock?” He waved to encompass the erratic, and the tenantless stretch of carbonized desolation around it.

The foreman nodded, big hands jammed into the front pockets of his jeans, leaning back phlegmatically.

“How do you know it’s the huldra’s rock?” he groped for a counter-argument, nettled by the man’s assurance. “I don’t see any sign on it or anything.”

The foreman scrutinized him indulgently. “It’s obvious,” he responded. “Stands out a mile. Anyone can see that it’s a huldra’s rock.”

One or two others nodded in agreement. Nielsen opened his mouth for a second, closed it, looked around once more at the men standing in a motley half-circle with the empty land behind them; then nodded hesitantly and turned the theodolite on to a new bearing to the left of the rock.

Satisfied, the foreman pulled his hands out of his jeans and clumped back towards the small parked convoy of huge-tyred high-wheelbase Japanese 4x4s.

Occasionally, Nielsen had to wonder what he was doing working on this island near-continent, surrounded by such people. Denmark could hardly be more different, despite the historical ties. And although the place scored high on all the approved metrics of civilization – parliamentary democracy, income per capita, mobile connectivity, and so on – there were times like today that really brought home the fact that he was marooned in mid-Atlantic, huddled just below the Arctic Circle, and cut off from the rest of humanity by a thousand kilometres of cold grey swell. His sense of isolation took on a fearful added emphasis at such times.

That was the only incident of the day, however, and they returned that evening in the long twilight of the northern summer to Hvolsvöllur, their base for this phase of the project. As they drove homewards, green crept back into the landscape, first a few tentative stipplings of grass in the gullies, then broader, more assertive swathes, until finally there was a smooth sward blanketing and softening the lowland’s contours, narrow strip fields, and a few stands of gnarled dwarf birches left by the reforestation projects.

Hvolsvöllur was a small settlement of a few hundred souls, on the Route One coastal ring road west of Vik but inland in the swamps of the Landeyjar, a scattering of aluminium-faced houses roofed in corrugated iron and painted in bright nursery colours like a toytown on the meadows’ flat green baize, sheltered by some domesticated trees, shops and suppliers for the local farmers, and the red and white Hotel Anna where they had put up. The bleak majesty of the surrounding environment had left no imprint of hardship on the place, no noble stigmata of endurance and suffering; rather, it seemed to have purged away all the excess fripperies of decoration and culture, so that the place had a bland faceless industrial uniformity, like a suburb with no town.

Facing the hotel was the bar, and it was there that they retired after dinner for a few lagers. Adam still felt a stranger among his workmates, dyed-in-the-wool Icelanders to a man and stoical navvies to boot, but he preferred to keep them company.

Midweek the bar was almost empty, with only a couple of locals leaning over their beers. Threadbare white drapes screened out the late evening sun, glowing palely. The workers ordered their jars from the lumpy, taciturn barmaid and clumped over to the jukebox or engaged the pair of tired-looking whores in one comer of the room.

Adam nursed his beaker of Thule, seated at the counter. The TV mounted on a bracket in the corner angle of the ceiling was recycling some old Bjork video.

“You know this is the setting for Njál’s Saga?

He turned at the light feminine voice. He must have been more engrossed in the screen than he had realized, because the girl had stepped up to the bar, sat down, and ordered the vodka cranberry on the counter in front of her without him even registering her presence. Now he looked at her. She was a natural brunette, with pendulous masses of dark curly hair, and she had the brightest, clearest blue eyes, as though the sky was shining right through her head from behind. Her body was lost under the nondescript parka, but she seemed both young and full-figured.

“No. I didn’t,” he answered finally.

“Oh, you’re a Dane; then I suppose l’m not surprised,” she continued. “You have no idea what you’re missing. It’s an awfully grim tale: nothing but revenge and tit-for-tat killings. Our forefathers were a bloody, quarrelsome, litigious lot.”

She had segued into perfect Danish, with a trace of an Icelandic accent, so smoothly that he had hardly noticed that they had switched languages. Adam’s smattering of Icelandic was one of the qualifications that had landed him the assignment: legacy of a grandmother who had insisted on telling him the old tales in the tongue of her own long-lost childhood.

“It’s not a matter of nationality: I never studied literature much. I’m a surveyor, working on the road improvements out by Myrdallsjokull,” he explained, rather superfluously, as he was still wearing his big work jacket with the dayglo stripes.

She regarded him sceptically. “Oh, I see, Mr Surveyor, a professional qualification is an excuse for ignorance, eh?” she chided. “Well, would you like to hear the story?”

“Yes please.”

She gave him a faultless five-minute précis of the saga as though she had rehearsed it, dwelling with almost intimate concern on the generational interweaving of blood ties and obligations. Her descriptions were as vivid as if she had been there herself to watch it all unfold a thousand years ago.

“So what are you doing here, researching for your literature thesis?” he asked at the end.

“Not at all, I’m a volunteer working for the forestry club,” she beamed brightly. “You know, once long ago this whole part of the country was covered in forest, before men came along and hacked it all down.”

“I heard they had this small thing called a Little Ice Age as well,” he countered gently.

“Pah, made about ten times worse by humans taking all the trees for firewood,” she dismissed him. “Anyway, we’re making some kind of atonement for past follies by helping it come back now.”

“Amen to that,” he replied. “So what should I call you?”

“Hella, like the town” she answered, after looking at him speculatively for a moment. “You know, just up the road from here. And what’s your name?”

“Adam,” he declared. “Adam Nielsen, like the composer.” They shook hands. Her fingers were pale and cool, firmer than he expected but with no trace of calluses or dirt.

“Son of man, eh?” she mocked him mildly. “How about a good old pagan Norse name like Ragnar or Thorfinn?”

“I can’t answer for my parents. It’s not like l had much say in the matter.”

“Pooh, you should have bawled louder at the christening.” She pushed back her stool and lifted her buckskin shoulder bag from the backrest. “Are you going to be staying long in this garden, Adam?”

“A few weeks longer, while we finish this stretch of the road.”

“Then perhaps we should catch up with each other some time,” she suggested, shrugging her bag onto her shoulder and fixing him with that clear blue stare.

“I’d like that,” he answered, pulling out his mobile phone. “What’s your number?”

“Oh, I don’t have a phone,” she laughed, waving a hand airily. “I don’t like those microwave emissions. Just keep an eye out for me: its a small town and I’m sure we’ll bump into each other.”

And with a fling of her fine dark hair, she was gone. That lustrous mare’s tail of black waves hung before his eyes long after her departing back had receded out through the doorway of the bar and down the street.

The next morning took them back out to the same section of road, several dozen kilometres inland from the coast, a tentative scrape in the tephra, warily tracing its way northwards between the volcano and the glacier, fire and ice. Adam duly surveyed a route that gave the huldra’s rock a wide berth. Directing the navvy who had been designated his assistant for the day, he noticed there was some strange interference in that area of the valley floor. He shouted into his walkie-talkie as the man stood motionless 300 metres away, holding the striped surveying pole, telling him to move to the right, but only a few faint bleats of static came from the handset. Finally, he was reduced to using hand signals.

The weather was fine and fair, with just enough breeze to keep down the heat and mosquitoes of summer. At lunch, they took a break in the natural hot springs by the valley wall, where a stream flowing pure and clear between black weedless beds of lapilli. As he splashed with the other men in the tepid water, Nielsen gazed upstream ? towards the steaming salt-encrusted fringes of the source pools, where a frog or man jumping into the water would have been parboiled in a blink. Wisps of pale vapour hung above the sulphurous cauldrons, filling the air with a faint whiff of the same rotten-egg reek that perfumed the streets of Reykjavik.

Nielsen seldom saw any sign of the famed happiness of the Icelanders in the men, who habitually were as stolid as fenceposts. But this time, ducking and laughing stark naked in the hot spring, he saw their warmth emerge, drawn out by the surroundings, from under the cold dark beds of long winter darkness and solitude. They could have been boys splashing in the bath together.

By evening, they were back in Hvolsvöllur, though with no special plans for another night of drinking this early in the week. Nielsen glanced around as he locked up the 4×4 for the night, half hoping to see the girl again.

“Hello again.” He looked around and there she was, wearing the same Goretex parka as before. Strange he had not noticed her in the street a moment ago: she must have popped out of a side road. Her blue eyes were as luminous in the open air, jewels emerging from the rough bag of the parka hood.

“Hella? Good to see you. How are you?”

“Oh, the same as always,” she shrugged brightly. “Is work keeping you well?”

“I suppose. It’s lucky to run into you again like this.” In daylight, she seemed to stand out very distinctly from her surroundings, as though undercut or in silhouette.

“Pooh, luck has nothing to do with it.” She waved her hand. “One main street, you see everyone here sooner or later.”

He slung his work bag on his shoulder more comfortably. “So, you come from around here?”

“Not exactly. My family do, but I’m not really in touch with them any more.”

“Oh? How come?”

She sucked her lip. “Look, if you’d like to hear the full story, perhaps I could tell you later this evening?”

“Uh… sure, would you like to meet up for a coffee or something?”

“I’d rather get dinner: I’m famished after a day in the plantations. Around eight? I’ll meet you in front of your hotel.”

Washed and changed into a fresh shirt, he stood waiting at eight o’clock. The few passers-by in the street were some distance off, as though warded away. As before, she appeared suddenly behind him, and he stood transfixed for a blink: she hadn’t seemed the kind of girl who would have a dress like that, certainly not here.

“Aren’t you cold?” he asked uncertainly.

“Of course not,” she chuckled, cocking her head. “Well, where are we going?”

He took her bare arm and led her to the town’s only authentic local restaurant. There, surrounded by timber and gingham kitsch, they ate well enough, though he balked at some of the more outré Icelandic delicacies.

“Rotted shark meat? Ram’s testicles?” He queried a dubious-looking patty with his fork.

“Call yourself a Dane?” she chided him gently.”There’s nothing wrong with it. Our forefathers used to snack off this like peanuts. It’s food of the soil.”

He flinched, screwed up his courage, and nibbled a tiny slice. It was suitably disgusting. Having proven his manhood by chewing a sheep’s balls, he left the delicacies alone for the rest of the evening. Hella fixed him with a laughing blue gaze and told him tales of the place and the sagas, the landscape and the glacial cold of winter. Soon she had him opening up and sharing details of his parents and sister back in Copenhagen, summers at the family chalet, picnics in the Tivoli, university, training and career.

Sitting across from her, he could appreciate details that had escaped him before, helped by the generous sweep of her dress as it fell away from the high backline. Her breasts curved under the fabric, rounded and firm as russet apples, for she seemed to have picked up a light all-over tan from her work in the plantations. And she had a strange way with her: she told stories and myths of distant times with fierce intensity, as though they involved her personally. But on details of her own family and past, she was surprisingly vague.

“It’s not important,” she insisted, brushing off the details of personality, biography, past, as though there was another order of things which rendered them meaningless. “I told you I don’t keep in touch with them, and there’s nothing more to it. We just aren’t that close.”

There was no point pressing the issue, and he was too captivated by what she did have to say.

When the meal was over, she walked at his side back down the main street, leaning on him. Despite her full curves and the firmness of her body against his side, her arms rested on his as light as a feather on the wing. Twilight was still incomplete at this time of the year, with a narrow amber band of radiance still rimming the west, but the streets were empty, blinds drawn down and shutters closed along both sides.

“You know that you can get a real midnight sun here sometimes?” she said, squinting at the sombre afterglow. “We’re not quite in the Arctic Circle, but refraction bends the sun up over the horizon, and you get full 24-hour daylight.” The pale sky backlit her, once again creating that strange illusion of flatness, as though her body was an oil film on the surface of a lake.

“I’m just glad I’m not here for the winter,” he shivered.

“Oh, it’s not so bad,” she beamed, still looking at the sky. “Firelight, Yuletide, cosy cabins, long long hours tucked up indoors with nothing moving outside but the aurora sparkling on the snow.”

Involuntarily, he kissed her, bending down to cut the light off from those shining eyes. Her tongue darted expectantly into his mouth with vixen cunning, pocketed and socketed in the warm wet narrow spaces beside its mate. They stayed locked together like that for many minutes in the gentle twilight, undisturbed. One or two cars slid past without slowing.

Finally, she took her mouth from his. “My hut’s just up the road,” she breathed, staring up at him. He let her lead him through the side streets and across a dirt track to the forestry plantation. He knew she was staying there, but was still surprised to see that her shed really was a shed: a one-room plank shack with a single window. Most of the dark, musty interior was filled with gardening tools and bags of compost and fertilizer: the soft earthy smell was actually pleasant, a little capsule from a more fertile, temperate clime, where there were proper forests and green hedgerows. On one side, against the wall under the window, there was a small three-drawer cabinet with a few personal effects strewn on top, and a narrow single bed.

Just as he was about to make some remark about the sparseness of the fittings, she pulled her to him and glued her mouth against his once more, tugging at his clothes. After that, he had no care for anything else. The small, detached part of the mind that floats free when the rest of a man is completely engaged in a woman observed that she seemed to pull at him as though desperate to keep him focused only on her, jealous of the slightest glance or thought that he cast elsewhere. If it was insecurity, she need not have worried: he was enraptured, clumsy, aggressive in his greed to get as much of her as humanly possible.

As his fingertips wandered over her back, they encountered gnarled ridges, beginning just below her nape. She flinched, and gently drew his hands away and down.

“What is it?” he asked. They were the first words he had spoken since entering the shed.

“A scar, from when I was a kid,” she explained diffidently. “My mother tripped and spilled hot coffee down my back.”

That would explain the coolness between her and her parents, thought the little objective nub. It was the only shyness or hesitation she showed, though, as she pulled him on, and he went into her with no protection. Her panting was like a persistent, recurrent sigh, some eternal regret caught in an endless loop, but it finally wound to a conclusion as she climaxed. Spent, he slumped across her, noticing how cool and dry her skin still was despite her exertions, her heart pulsing under her breast like a rounded drumhead.

“That was… marvellous,” he breathed. Her fingers wove patterns in the hair on the back of his neck.

“Welcome, Mister Dane.” She pecked him on the forehead. “I was pleased too.” She spoke in the tone of a virtuoso who had just recorded a particularly difficult solo.

“You know we didn’t use a condom?” he remarked.

She paused for a moment, as though suddenly robbed of speech, so still and silent that he thought she was in shock, then shrugged dismissively. “No need to worry: it’s my least fertile time of the month, and I’m a clean girl, so don’t you go worrying yourself.”

“Oh well. Anyway, that’s one way to get through the long, dark winters.”

She stared at him wide-eyed for a moment, them dug him in the ribs. “Kidder. And look at you, the mysterious stranger, waltzing into town and sweeping a poor young girl off her feet.”

“Oh, there’s nothing that mysterious about me,” he replied, truthfully enough.

The scents of summer slipped in through the shed’s thin walls, mingling with the earthy breath of the compost bags and planters. They slept in balmy comfort, wrapped round each other on that low pallet, and towards dawn, made love again, less feverishly this time. He had just enough time after he kissed her goodbye to shower and change into fresh work clothes in his hotel room, before joining the rest of the crew in the car park.

Strangely, no one mentioned the girl or his absence the previous evening: he had expected some half-envious ribbing, but none of the road gang seemed to have even noticed. They exchanged a few monosyllables in the hermetically sealed hush of the 4×4’s passenger compartment, the bare bones of a conversation as sparse and arid as the landscape outside. There seemed to be no point bringing it up, so he rode in silence with them out to the next stage of the new highway, nursing the warm ache in his groin, already anticipating the evening ahead.

Over the next few days, they settled into a routine, meeting in the car park or outside his hotel, choosing from the few restaurants and cafes that the town had to offer, strolling together afterwards in the long twilight before going to bed. She avoided mixing with his colleagues, who themselves phlegmatically ignored her. She also preferred her hut to his hotel room, and indeed she looked out of place in the antiseptic white sheets, against the anonymous sterile motel chic. And she would not let him see her back; pressing herself against the mattress or draping the covers over her shoulders like wings.

“I don’t like to show it,” she explained. “It’s not like it hurts or is that disfiguring, but I’d rather not have anyone stare.”

“I don’t mind,” he remonstrated with her, trying to catch both her hands in his. “No matter how bad it is, it can’t change how I feel about you.”

She pursed her lips and hunched her shoulders, nestling even deeper into her new white plumage.

“Trust me,” he urged, stroking her shoulders through the sheets.

She shook her head. “I do trust you, but it’s personal. Please don’t keep asking.”

And she looked up at him with huge beseeching blue eyes, stilling his arguments, and his doubts.

Usually the weekend was a dead flat time for Nielsen, stranded up there in the dull small town with no entertainment to speak of, waste time to wait out until the next working week began. At first, he had made a few mercy dashes to Reykjavik, to burn off his boredom in its fleshpots, pervaded by the ubiquitous, sulphurous stink from its geothermal hot water system, but the trip down the coast road took so long that there was hardly any time for fun at the far end, and he soon gave up on it. Now, though, he looked forward to the free time with Hella.

On their first Sunday together, after spending almost the whole of Saturday in bed, they took Nielsen’s 4×4 up to Thorsmork, to see the magnificent valley. They parked in a layby and climbed up a spur of the glacier-carved ridge to look down on its sun-dappled length. The grey and dun ash, the sparse coverage of greenery, left the landscape rather half-finished, like a charcoal sketch on a body-coloured ground with most of the details still to be filled in. Against that stark backdrop, colours and details stood out all the more sharply, swept over by the wash of light and shade that the sharp wind blew across the terrain. Tawny patches of dried grass in fawn and ochre intercut with a fresher lime where water or thicker topsoil greened the turf. The streams themselves dyed the grey cinders inky black, or sparkled clear and glassy in their graven channels, slicing deep knife-sharp canyons into the soft, loosely compacted tuff of the valley walls.

Once up on the ridge, Hella stretched both her arms up above her head and whirled round on the spot with a loud “whee,” her dark hair flying loose in the fresh breeze. Laughing, he caught her round the waist and lifted her off her feet, marvelling at her lightness, but she pushed free of him, grinning, and ran off uphill towards the dark ridge wall at their back, casting an occasional mischievous glance over her shoulder, daring him to pursue her, gambolling almost like a young doe.

The hillside ascended in irregular broken terraces towards a waterfall where a torrent from the glacier far above spilled over the lip of the ridge. As Adam scrambled up by the steam bed, he lost sight of her. Breasting the rim of the bowl surrounding the plunge pool, he looked up and down its banks, but she was nowhere to be seen. White spray filled the air, sparkling in the pale sunshine, obscuring his vision.

He called out her name, but the continual din of falling water drowned out the sound of his voice. With no alternative, he started to work his way along the side of the pool, peering through the spray. Then he caught sight of her dim outline, standing facing towards the waterfall, her arms still upraised, as though venerating it. He stumbled over to her and called her name again, from close up. After a moment, she noticed his presence and turned back to him, lowering her arms. As her gaze met his, there was a momentary hiatus, like a skipped frame in a video playback, before she focused on him again; for that moment, her eyes were dark and empty as knotholes in bark. Then they filled with the old light and warmth, and she smiled at him coyly.

“Out of breath, dear?” she teased.

He laughed and reached for her, to dispel that instant of unease as much as anything, and in a moment they were shouting and chasing each other round the pool again. They fell winded to the turf and made love, surrounded by the earth and sky, warmed by the strong pale sun, the clear summer air mercifully free of mosquitoes.

During working hours, he caught himself yearning for her, wishing she had a mobile so he could call her. Occasionally he found his mind drifting, far from the job in hand. The Icelanders noticed and muttered to each other, but said nothing to his face. Almost every evening, though, there she was, waiting at the kerb when his car pulled up, ready for another meal together, another short promenade in the long dusk, another night.

Subtly, she grew more pressing, more importunate, though with no grating edge of insecurity; he honestly felt that she valued her time with him and wanted more of it. She had her own unknown duties with the forest service during the day, but even that, he felt, was now open to discussion.

“Can’t you take a day off?” she asked one evening, hanging lightly on his arm as always, by her fingertips. “I want more time with you.”

“I want more time with you too, but I’ve got a job to do. That’s why I’m here.”

“You shouldn’t treat it so personally,” she pouted. “Don’t I matter to you?”

“Of course you do, but what do you think brought me here in the first place?”

“I don’t know: destiny?” she shrugged.

“You shouldn’t talk about it in such grand terms: it was just a contract.”

“You shouldn’t talk about it in such petty terms.” She had a way of speaking with her fingers, very tactile, as though words were insufficient or unreliable and meaning could be blown away in the airy spaces between people, tapping and pressing on his skin almost like a court stenographer. Right now, they were probing insistently at his forearm, searching as though for a way in. “I’m here for you; and you’re here for me. Do you have to dismiss it like that?”

“Alright, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean it that way,” he conceded, stroking her hair. “I just think too much like an engineer sometimes.”

“I know,” she complained with a little hurt moue. “You could be a bit more romantic. You know, I feel so empty when you’re not around, like I’m not all there. You fill me.”

Still, the topic of the day off did not come up again, and they kept to the old routine, as though present habit could exorcise any questions about the future.

On their third weekend together, Hella took him round the town’s pocket museum, the Saga Centre, to broaden his education, she said. Walking back towards the hut afterwards, she seemed distant, abstracted, looking through the walls of the houses on either side towards some unseen horizon. As he saw they were wending back towards her hut, he tried to make a case for going back to the hotel instead.

“Don’t you get fed up with living in a hut? Wouldn’t you prefer something a little more comfortable?”

She sucked her lower lip. “It’s not that bad. Remember, I‘m out with the trees most of the day.”

“Still, a few more table and chairs wouldn’t do any harm.”

She extended her right arm, thumb spring-loading her forefinger, and deliberately flicked the corrugated iron wall of the house beside her. The painted metal rang loudly.

“I don’t ever feel at home living in these tin cans,” she said tonelessly, her eyes hard and distant. “Hollow shells, with trinkets and lives rattling around inside them. I want to be close to the earth, where things are solid.”

“Just a bed between some sacks of fertilizer and a few odds and ends is hardly that solid,” he objected.

“You think these houses are that much more solid?” she countered, bridling. “Remember the Mist Hardships when Laki erupted? Sulphur fog over the whole country, half the livestock dead, a quarter of the population starving to death, no get-out, no appeal. What carnage, eh?” And she smacked her lips with slightly alarming relish. “And that was only two hundred years ago. It’s only been a few years since Eyjafjallajökull erupted and we had to host the Red Cross up here for all the evacuees. And that road you’re building runs right up between the two volcanic zones. This place is just a thin crust over an ocean of fire, and it could all be blown away, just like that.”

“I couldn’t live all the time in a hut, though. I’d want something more substantial around me.”

“I didn’t think that mattered to you.” She glanced at him, tone cooler, but expectant. “I thought you were moving on soon.”

“The plans aren’t settled yet.” He shrugged, careful to stay noncommital. “And we’re still not sure where the base for the next stage will be.”

“Maybe you could stay a while?” she moved into the shelter of his shoulder, eyes wide, angling her head up to gaze into his, then calmly said. “You know, you could quit and stay here with me.”

He looked at her. “And give up my career?”

“Why not?” she smiled nonchalantly. “We’d be together.”

“And what would I do?” he asked, unaccountably uneasy at the direction of the conversation. “How would we live?”

She shrugged airily. “Oh, people always find a way somehow.”

“But I have responsibilities, a profession,” he protested, unsure how serious she was. “I can’t just turn my back on all those years of study and work: what a waste it would be. And I make good money: I don’t want to give that up.”

“Pah, Mr Money,” she tossed her head dismissively. “I’ll show you what’s worthwhile.” And she kissed him hard, stifling his protests.

Time with her grew easier and calmer, but time by himself grew more fraught and burdened as he considered what to do. At almost thirty, he had honestly thought about settling down even before she came along, but he was still not sure whether he was quite ready to give up a decade’s habits and concede.

And it was very short notice to start making choices that might affect his future. Besides, there was still so much about her he did not know, though she breezily dismissed his questioning as though his concerns were irrelevant, almost surprised that people needed to know such things. She was eloquent, persuasive, and also, he thought occasionally for brief fleeting moments, just the tiniest bit sociopathic.

He would be a lot easier in his mind if he could be clearer on what he might be committing to. If he changed his plans now, he felt, he might already be granting all kinds of hostages to fortune, and since there was not the time to let the relationship evolve naturally to the point where the choices became inevitable, the onus was going to be on him to make a decision.

Pondering, he slid the 4×4 into the outskirts of Hvolsvöllur, already packing those concerns away into the back of his mind ready for another warm, relaxing evening together. Missing her figure on the pavement in its customary spot, he pulled up and got out of the 4×4. A wizened old vagrant in a greasy brown mac belted with string, with an ancient sou’wester pulled down low on the back of his neck, stood on the kerb where Hella usually waited. He turned his head and leered at Nielsen. Under the torn brim of the sou’wester, a soiled wad of bandage was taped over one eye socket, tumescent as a scuffed puffball on a rotting log.

“That’s a pretty girl you’ve got there, laddie,” he sniggered, baring yellowed stumps of teeth in liver-spotted gums.

Nielsen stared at him. The old tramp leered back, single eye maniacally bright.

“I’ll bet she bucks,” he crowed, spreading his cracked purple fingers in a open-mittened grip and thrusting his pelvis forward.

Aghast, Nielsen took a step towards the old man, uncertain whether to turn tail or attack him. The vagabond stood his ground, his almost square body swaying slightly with a meths-drinker’s tremors, still staring. He heard Hella’s voice calling him somewhere off across the street, and turned to see her hurrying towards him. When he looked back, the old man was gone.

“Where were you?” he asked. She looked slightly flustered and on edge.

“Nowhere: just got caught up on my way here. What’s the problem?”

“Nothing,” he replied, deciding not to mention the old man. She linked arms, with him, and they went off together to eat pizza.

Work on the road began to slow amid signs that the short Icelandic summer was nearing its end. More than once, they had to carefully push the 4x4s in Indian file through sudden flash floods at the fords: the crystal-clear fine days grew fewer and fewer. Weather reports on TV and radio became a matter of daily concern. Hella, too, became as skittish and unpredictable as the rainstorms and gales: swinging between febrile excitement and unaccountable bursts of anger. Nielsen hardly minded: if anything, her new moods made the sex even better.

That Sunday, they planned another picnic, this time in the lee of one of the fossil lava flows, where convolutions of molten rock had ossified in a crazily rucked quilt of folds, softened by blankets of moss and emerald grass, Nature’s stony maze hedged in by evergreen pumice. They took a path along the crest of one of the ridges, where they could drop down between the creases, out of sight of other wanderers. But the lowering sky put all thoughts of lovemaking out of their minds, and they munched their packed meal almost in silence, looking out across hectares of trackless, dark crevasses.

“Storm coming up,” Nielsen remarked, hands on hips, pivoting and sucking his lip as he surveyed the grey horizon. “Perhaps we’d better get back.”

Hella seemed distracted, head ducking, not really looking at him or the sky, jaw thrust forward as though she was trying to catch a scent. Instead of her normal radiant self, she looked worn and furtive as a harried vixen. She said something indistinct that sounded like a reply, or a refusal. Thick dark clouds were gathering along the sky’s western rim, towering and baleful.

“Darling…” He touched her on the shoulder. She jumped at the contact and stared at him, and the strangest thing happened: he saw her pulling away from him without moving, splashed strangely flat against the dour background, like a dolly zoom on film.

“What’s wrong?” he asked. With a look of sheer desperate panic, she broke and ran along the flow, up towards the crest of the ridge, where it dipped and converged with the other corrugations.

Pausing only to snatch up the packsack with their gear and the remnants of the abortive picnic, he ran after her, but she was dashing full tilt, arms and legs flailing, and had already opened a lead. In moments, she was lost to view, slipping out of sight in the labyrinth of chasms. Sudden gusts clutched and snatched at him as he ran, bearing a distant dull rumble, and all along the darkening western rim of the sky, a ramparted wall was advancing, bright flashes playing around its thunderheads.

The convoluted lava could have swallowed an entire war band, and rather than struggle in vain to catch sight of her, he worked his way by intuition along what he thought was her path, eastward and uphill, towards the larger ridge that loomed above the head of the old fossilized flow. Light was fading from the sky as the stormfront loomed nearer, and dull concussions rang through earth and sky like hoofbeats. Though she was still wearing her parka, he feared for her once the storm broke, quite apart from her inexplicable panic fit.

The summit of a lava fold gave him a brief wider view, and he caught sight of a struggling figure upslope in blue, toiling over the gradually diminishing ridges. The stampede of cloud thundered down on them, roaring. Lightning was flashing in earnest now, spraying lurid highlights across the gloomy murk under the cloud base; curved and keen as a gutting knife. The rain had mercifully held off, but he could see black squalls darting here and there across the wilderness, roving cloaked and menacing over the fells.

The lava field petered out into an obstacle course of ankle-high furrows before finally disappearing completely into the sleep basalt scarp of the fell. There he stopped again, breathing as wildly as the wind gusting around him, ribs aching and spots dancing before his eyes from more than the lightning bolts. Bent over, hands on his knees, he raised his head and saw a familiar outline on the fellside up above.

“Hella,” he yelled, at the top of his voice.

She turned back towards him in one wild movement, just as she reached the crest of the dark ridge and stood silhouetted on his horizon, and for a moment, though he could not be sure if he was seeing some reflection from the ringing sky behind him, it seemed as though he could see the lightning bursts in the sky behind her, flashing through her eyes. Then she dropped out of sight behind the ridge, and the rain, long restrained, came thundering down.

He gasped and choked in the downpour, squinting water out of his eyes. The fellside above was awash, a sheer mud face sheeting with water. By the time it had abated enough for him to scramble and skid up to the crest where she had stood, there was nothing and no one to be seen: just a tenantless expanse of wasteland shaded by the ebbing storm, overlooked by a narrow ledge where even footprints had been washed away.

He scoured the fell, splashing though the sudden mud puddles, calling her name, but there was no sign of her. As the last storm clouds withdrew over the western horizon, he trudged back to the car, thinking she might have made her way back before him: still no sign. Disconsolate, he got in and drove back to town, mystified. His faint hope that she would be there, waiting for him, at her usual spot on the pavement, was disappointed. At a loss, he made his way to her hut on the forestry plantation.

The shed stood forlornly in the wet yard, its door on the latch. Nielsen opened it and looked inside. The bags of fertilizer and seed were as he remembered, and the bed was still in its place, but it was bare and without sheets or blanket, just a crash couch with a mattress for a nightwatchman to take a rest on. And the small cabinet by it was bare of all personal effects, missing even the cotton cloth over its top: just stark metal.

Now thoroughly confused and alarmed, he went to the town’s small police station, and gave her details to the bored young constable on duty.

“There was some thunder over towards Thorsmork, but I don’t remember any storm warnings,” the constable grumbled. “Still, we’ll look into it. Could you fill out this form?”

Nielsen realized that Hella had never told him her surname or her age. The constable gazed at him incredulously.

“You want me to file a missing persons report for a girlfriend whose name you don’t even know?” he asked.

“I only met her recently. She’s a student volunteer working on the reforestation project,” Nielsen explained feebly.

The constable gazed at him. “There’s no one working on the reforestation project,” he replied.”They finished the planting years ago.”

Moved by Nielsen’s obvious distress, the constable finally agreed to drive out to the fell with him in the fading light. Approached by road from the uphill side, the lava crag did not seem that formidable, and Nielsen sheepishly led the policeman down for some distance over the scoria maze, but the whole scene was now calm and bare, with nothing to suggest danger or mystery. All he could do was get back in his 4×4 and follow the police Volvo back into town.

Nielsen passed an anxious, sleepless night in his cheerless motel bed, staring at the roof panels and waiting for a phone call or a knock on the door. In the morning, he walked out to the plantation once again before breakfast, but the hut stood as empty as when he had last seen it. Mechanically, he followed the rest of the crew out to the worksite and surveyed a few more tens of metres of road across the blank grey ash plain. When they returned that evening, he scanned the roadside, hoping for Hella to be standing there unannounced, just as before, but only a few local passers-by trod the pavements.

The same pattern persisted over the next few days and nights. He took to going to the bar again, with the others or alone, morosely nursing an aquavit, ears cocked for the swing of the door. Towards the end of the week, they finished the current phase of the project, ending the survey at an arbitrary point in the wasteland,

ready for a move up the road and a change of base camp prior to the next stage. They chinked flasks at the kilometre mark in a little ceremony.

“Still got your mind on that girl?” the foreman asked, as they stood together cradling the metal phials of spirits.

Nielsen started and nodded. He hadn’t credited the foreman with such insight.

“I saw you two together,” the foreman continued, compassionately. “She was lovely, but she was a fey one. I always thought that sooner or later she’d give you the slip.”

Unable to reply, Nielsen looked away, to the horizon where a few grey clouds were tumbling along, recalling those eyes that were like the sky shining straight through the back of her head. A stray breeze gently ruffled his hair.