A review of Tales from Arkham Sanitarium

Edited by Brian M. Sammons

208 pages

Dark Regions Press

The premise of this new collection of Lovecraftian horror is straightforward and right on point. As the Dark Regions Press blurb declares, “the insanity that follows in the pursuit of damnable truths, is at the core of many of the stories of the Cthulhu Mythos. Insanity is central to Lovecraftian horror, so there is no wonder that in his witch-cursed and legend-haunted town of Arkham, a cathedral devoted to mending broken minds was raised.” These 15 stories weave variations on that theme, although not all of them are set in the titular sanitarium. It’s obviously a theme that appeals to some highly gifted authors because the contributor list includes some of the leading lights of current weird fiction. Orrin Grey, Nick Mamatas, Cody Goodfellow and Jeffrey Thomas are anything but run-of-the-mill Lovecraft pasticheurs, and the quality of their contributions is correspondingly high.

All credit to the editor, then, for having marshalled them under this banner. Brian M. Sammons is a serial author, editor, anthologist and game designer of dark, horrific, and predominantly Lovecraftian works, and he secured all new original stories for this volume. He told me that “I’ve always liked to do unusual themes for my Lovecraftian anthologies. It’s not enough to just have good cosmic horror stories. I’ve done Lovecraftian anthologies set in the 1950s and 1960s, during wartime, in a cyberpunk future, in a steampunk past, and more… the idea behind Tales From Arkham Sanitarium was a focus on another staple of weird fiction and Lovecraftian horror: madness. I wanted stories that delved into the insanity associated with the Cthulhu Mythos, how it affects survivors and witnesses of things from beyond, how learning the things man wasn’t meant to know can burn, and how cultists and fanatics get that way. So that is what I was aiming for with this book and I think the authors nailed it.”

When the protagonists of these stories do get into Arkham Sanitarium, their ways and reasons for doing so are refreshingly different and interesting. Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation may sound like a really fantastic name for a band, but it’s far less appealing when they’re also a conduit for unnatural contagion, as in the tale by William Meikle. A talking house, or rather, a protagonist who isn’t sure whether they are a person or a house, is definitely a new one on me, but that’s what Christine Morgan manages in “Let me Talk to Sarah”. The stories from W. H. Pugmire and Joseph S. Pulver, Sr., are both among the last that those sadly-missed authors ever wrote. It’s good to be able to report that they are also among the highlights of the volume. Pulver’s story in particular is a virtuoso fantasia with his characteristic typographical and stylistic extravaganzas, almost as delirious as the subject matter, and a real reminder of how irreplaceable his talent was.

One interesting and perhaps telling aspect of the whole exercise is the frequency with which the narratives switch from Arkham Sanitarium to what appears to be almost its sister Arkham institution, Miskatonic University. Many of these sanitarium incumbents are former residents of the university, and in some cases that academic institution looms large, where the theme of madness continues but the sanitarium is hardly mentioned. As it happens, those stories include some of the strongest and weakest work in the book. Edward M. Erdelac’s “The Colors Of A Rainbow To One Born Blind” starts off as a terrific sequence of rolling evocations of favourite Lovecraftian tropes, before ending as a fairly conventional campus shooting bloodbath, all too familiar in fiction and in fact. On the other hand, Cody Goodfellow’s “Forbidden Fruit” is a disorienting exercise in seriously bad archaeology that has sunk its claws into my imagination like it wants to live there. It’s that characteristic Lovecraftian message: Knowledge leads to madness. Knowledge is madness. Madness and knowledge are two sides of the same coin. To paraphrase Lovecraft, the piecing together of dissociated knowledge has opened up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we have gone mad from the revelation – and the gates and cells of Arkham Sanitarium yawn wide to receive the enlightened recipients of such knowledge. Recommended.

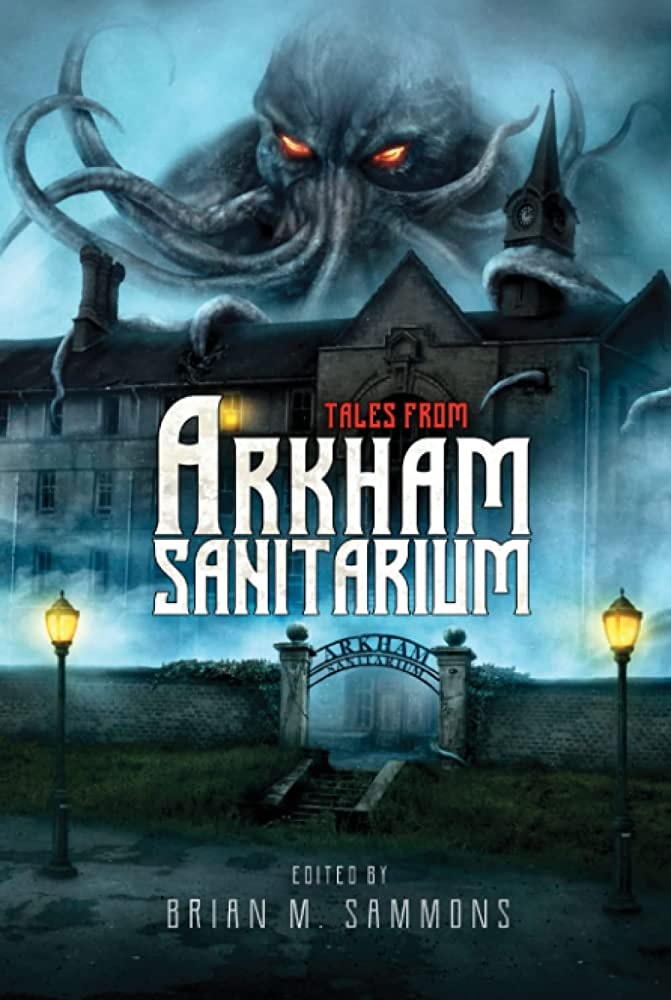

A review of Regency Cthulhu: Dark Designs in Jane Austen’s England

by Andrew Peregrine, Lynne Hardy and Friends

226 pages

Published by Chaosium, 2022

Your mileage may vary, but I’ve found that the more detail, meat and juice there is in a historical sourcebook for an RPG, the more I get out of it, and the more stimulating and just plain useful it is. I mean, there’s usually so much unexpected, fascinating, and crazy stuff going on in any one timeframe that you only need shake the box a little to have fabulous scenario seeds pouring out. That’s got to be worth the cost of admission, right?

So I was hoping for a lot from Regency Cthulhu. Did I get it? Well, in its 226 pages, the Introduction is basically all the generally explanatory material on the Regency era – and it’s only 16 pages long. Actually, half of that is a Regency timeline – so in fact, for this introduction to an unfamiliar, incredibly diverse and dramatic historical setting, we’re looking at a grand total of eight pages, with a lot of half-page illustrations to cut down that text even more. That’s close to the length of the setting introductions for each individual chapter of Masks of Nyarlathotep.

As the Introduction states, the book really focuses on the Regency as strictly drawn – the “reign” of the Prince Regent, between 1811 and 1820 – pretty much Jane Austen’s entire mature publishing career. Yet even within that period, there is so much fascinating and supremely gameable material that it leaves out. For instance, Byron, Percy Shelley, Mary Shelley, and Polidori had their great horror story contest on the banks of Lake Geneva in 1816, which produced Frankenstein in 1818. There’s Beau Brummell and the political shenanigans of the Regency itself. There’s the first steam engines. There’s the Peterloo Massacre. And then there’s the culmination of the Napoleonic Wars. Yes, those Napoleonic Wars – the Retreat from Moscow, the Hundred Days, Waterloo, and all that.

There are great cultural currents in the period that flow right into horror and horror gaming. I’ve already touched on a couple of really massive peaks that helped shape the entire horror genre. They’re often classed as the second generation of Gothic literature – and Jane Austen herself cut her teeth (pretty literally) on satirizing the first generation. Austen’s decorous, refined culture existed in dynamic counterpoise with the dramatic, hysteric excesses of Romanticism – John Martin’s apocalyptic canvases, William Beckford’s erection of his bizarre follies at Fonthill Abbey and Landsdown Tower, Walter Scott’s rediscovery of the Scottish Crown Jewels, John Polidori’s publication of his vampire tale The Vampyre, and so on, and on, and on. All of which features hardly at all in this book.

In Regency Cthulhu, pages 8 to 42 are devoted to the introduction, a general outline, and the period and customization details needed to create a Regency investigator. Some six pages are devoted to equipment and price tables, and other period details. The production values are high, yes – in the same current generic Chaosium house style, which is pretty solidly good (although perhaps a touch lacking in the kind of neo-classical feel that could have fleshed out the sense – and sensibility – of the period). And the rest is almost entirely devoted to three interconnected scenarios and their supporting handouts and pregens. I understand from podcasts that the book grew out of Andrew Peregrine’s own independently developed Regency scenarios, rather than the scenarios being commissioned to match the system. And yes, they’re three very good and playable scenarios, rich with the flavour of the period, and providing plenty of setting and character detail that can be worked into a campaign. But that is exactly how much this book gives you to create your own Regency setting and Regency investigators – the bare bones. The new Reputation system is a terrific addition to the Call of Cthulhu repertoire, and perfectly tailored to Regency society, while potentially being adaptable for Gaslight and other eras too, but it’s a new mechanic, rather than a presentation of source material for a sourcebook.

I sadly feel the lack in Regency Cthulhu of the phenomenal density of historical and cultural detail that went into Lynne Hardy’s brilliant The Children of Fear. It feels like an RPG version of Bridgerton – a costume pastiche whose knowledge of the era goes no deeper than its frocks. And I know that’s not representative of the authors’ knowledge or love of the period, but it’s all that gets through here. It’s kind of indicative in my view that the handouts include a one-page summary of the Regency era – presumably for players who can’t even be bothered to go through the fairly basic introduction to the period in the book. There is so, so much great gaming material and potential from the period that’s hardly even referenced in a one-liner. Fine, you can’t cover everything – but Chaosium has covered loads more, in supplement after supplement, in its recent production lineup. The Children of Fear, in contrast, is about twice as long, at 416 pages, and infinitely deeper in detail, even though its setting is far more alien. Or look at David Larkins’s Berlin: The Wicked City, with its dazzling and decadent recreation of the spirit and fleshy details of the Weimar period. And couldn’t there have been more genuinely period illustrations in the book, instead of just more Chaosium house style art, since it covers an epoch of fabulous imagery, from Gillray’s satires to Blake’s phantasmagoria? How about a map of Bath, or Regency London? Or some period pamphlets? I mean, call me an intellectual snob if you like, but I haven’t found any reason to complain about lack of detail in any of Chaosium’s recent sourcebooks and scenarios, and I’ve read and/or reviewed just about all of them. And those incorporate a great deal of input from some of the same writers. So if those standards were applied there, couldn’t they have been applied here? I know that the authors are huge fans of the period, and it’s a colossal shame that their enthusiasm couldn’t have been reflected in more material that is – well, source material. And yes, it’s true that some key modern properties about the period, such as Bernard Cornwell’s Richard Sharpe series, or Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey–Maturin cycle, are still in copyright, but Frederick Marryat’s Mr Midshipman Easy isn’t. Nor is Nightmare Abbey. Nor is Vanity Fair. Or Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley. Or Billy Budd. Or Shelley’s Zastrozzi.

I understand that other follow-up publications to Regency Cthulhu may be in the offing, and I’d really love to see a Napoleonic or Romantic CoC sourcebook from Chaosium to flesh out what this one has missed – because IMHO it does stand in need of them. (And no, I am not pitching for work myself here – just commenting.) Rather than a sourcebook, it reads like three extended scenarios with a fairly abbreviated historical background. Even the appendix updating the scenario setting of Tarryford to 1913 is longer than the consecutive space given to the source material; just turning those 9-10 pages over to real Regency content could have made this a hugely more fruitful and faithful resource for Keepers.

This is the first Chaosium product in ages that I wouldn’t rate as an instant classic – which is kind of praising with faint damnation, maybe, but there you go. I’m reminded painfully of the title of another great English novel that followed a bit later – Great Expectations. That’s what mine were. I realize Chaosium can’t roll a critical hit every time, but it’s a shame that this one had to be the one they missed on. Ah well, back to Reign of Terror.

[Top]A review of Vaesen: Mythic Britain & Ireland

164 pages

Published by Free League (Fria Ligan), 2022

Vaesen: Mythic Britain & Ireland arrives as a welcome, but hardly unexpected, pleasure. The Kickstarter for this supplement blew through its target in just six minutes, and finished over 60 times overfunded, with stretch goal after stretch goal unlocked. Was it worth the wait? Well, Free League is practically a guarantee of quality, and Vaesen is one of the best pedigrees a gamer could wish for. And Vaesen: Mythic Britain & Ireland doesn’t disappoint.

At 164 pages, it’s not the biggest roleplaying supplement you’ll ever see, but it has been produced to the same immaculate standard as the original Vaesen, with similarly superb artwork. Indeed, Johan Egerkrans, whose work inspired the original RPG, is lead artist for this production too. Lead writer is veteran gaming author Graeme Davis, who has been producing one-off creature sheets for Vaesen on DriveThruRPG for ages now, many of them very British. So you’re pretty much guaranteed something of Free League’s usual high quality out of the gate.

This is definitely an expansion supplement: you will need the original Vaesen rules to play the game. (What, you don’t have them already? How could you deprive yourself this way?) What you do get is a framing narrative to situate Vaesen: Mythic Britain & Ireland in the same old-vs-new 19th-century confrontation as in Vaesen’s Scandinavia, a guide to the British Isles of the time (mundane and occult), a society (the Apollonian Society, no less) to provide the same campaign structure as its sister organization in Uppsala, new character archetypes (the Athlete, Entertainer, and Socialite), thirteen new and very folkloric creatures to challenge investigators as well as guidelines on how to adapt existing vaesen to the British setting, and three very extensive scenarios ranging from Wales to Hampstead. As any Vaesen player knows, that should give you 16 new adventures out of the box, with each creature having its usual peculiarities and unique responses to conflict. Vaesen: Mythic Britain & Ireland players will likely have settled down into a long-running campaign before the GameMaster even needs to think of stepping outside the basic book to look up further sources and inspirations in the Bibliography. As with much Vaesen material, my only caveat is that I wish there could have been even more of it, but that’s a good problem for any game to have, and as said, there’s more than enough here to keep a gaming group busy for many sessions on end – well over a year’s worth, if you reckon on one session per week and an average of three sessions per creature or adventure.

Vaesen: Mythic Britain & Ireland is an expansion that the game has been crying out for ever since the original game debuted, taking the Vaesen experience into new and very fertile territory. It maintains all the charm of the original, while tapping into one of the richest and most thoroughly documented pools of folklore on the planet. And in the unlikely event that you ever tire of playing, you can always just sit back and luxuriate in the gorgeous pictures. Highly recommended.

[Top]A review of Vaesen: Nordic Horror Roleplaying, and Vaesen: A Wicked Secret and Other Mysteries

Illustration and original concept by Johan Egerkrans, writing by Nils Hintze and others

240 pages / 112 pages

Published by Free League (Fria Ligan), 2020

I won’t add to the many laudatory reviews of Vaesen from Sweden’s Free League (Fria Ligan) by just doing a straight runthrough of its qualities as an RPG. Rather, I want to use the game to pick a personal bone with the RPG horror landscape as it stands. It’s the bone that pulled me into RPG writing in the first place. So if the following review seems egocentric, I’m sorry; but Vaesen really doesn’t need me to speak for it – it can more than make a case for itself.

For a start, the game – inspired by and substantially created by the Swedish fantasy illustrator and author Johan Egerkrans – could well have been subtitled “Nordic Folk Horror Roleplaying,” and that’s all to its credit. For the purposes of this review, I could dub it “Trembling Without Tentacles.” When I wrote my first horror RPG, I did it substantially because I was fed up with the Lovecrafting of horror gaming, where every pantheon and every legendary being was warped into a manifestation of the Great Old Ones. Call of Cthulhu saturates horror gaming, or at least did so before the recent wave of indie RPGs, and the advent of Powered by the Apocalypse and the alternative rule systems typified by both the OSR movement and the minimalist “tiny” rulesets. For too long, Call of Cthulhu was the monocrop that cut out all other species of horror game from the light. I’ve had more than one horror RPG podcast recently remind me that Call of Cthulhu got to the table first, right at the start of the hobby, and has buttressed its position with reams of high-quality scenarios and campaigns, so that GMs and players need little added effort to immerse themselves in it and it alone for years on end.

That’s all well and good, except that horror gaming has so much more to offer than just tentacles and existential terror. Look, for instance, at the success of Monster of the Week, or Monsterhearts, or Alien, as very different takes on the horror genre that bring fresh and very enjoyable experiences to the gaming table. Look at the immense troves of fascinating material in the world’s folk cultures and traditions – all of which get distorted and bowdlerized as soon as they’re tapped for Call of Cthulhu gaming, into manifestations of Nyarlathotep and miscategorized Deep Ones. Look at ghost stories and psychic investigations, which get very thin coverage from Lovecraft (perhaps because of his nihilistic materialism), but which nonetheless are the very stuff of horror, and rich in potential for RPGs. When I wrote Casting the Runes, I did it exactly because Lovecraft’s legacy to gaming was cutting out or trivializing the great tradition of ghost stories that Lovecraft himself revered in his own critical writing. Look at all the different kinds of horror story that are totally unlike Lovecraft’s own vision of cosmic nihilism. It’s no wonder that Call of Cthulhu proved to be a superb base for some great board games when the underlying narrative thrust of so many Mythos stories is so repetitive and predictable.

So it’s great to embrace a game whose strengths are all about traditions utterly removed from Lovecraftian horror. Instead, Vaesen dives headlong into Scandinavia’s rich heritage of legendary beings, and comes up smelling all the fresher for it. The titular vaesen (supernatural beings) are described in loving detail, with 21 fully covered and more than enough guidance to create more based on the included templates. Each has its own unique Powers, and Conditions that kick in as the creature is stressed during conflict – for instance, the Ash Tree Wife dissolves into ash leaves when it’s defeated, while a Brook Horse can lure or grab a victim in its teeth and drag them off for a mad brook ride. The mid-Victorian, vaguely steampunk Scandinavian setting is not only flavourful, it also supports the trope of modernity versus tradition which is one of the game’s major themes. A game which unapologetically presents folklore and established traditions, instead of jamming everything into the Lovecraftian cookie-cutter, not only has the attraction of new and interesting creatures to face, but also allows for a slew of different flavours of stories and themes. Instead of devolving to the persistent Cthulhu Mythos tropes of cosmic horror and an indifferent, malignant underlying reality, players of Vaesen can tackle threats no less menacing but with a whole different range of emotional registers. You don’t often get pathos from the loss or the defeat of the inexplicable in Call of Cthulhu and its ilk, but such topics spring up naturally in Vaesen. Both Christianity and Norse paganism can be brought to the gaming table in full, for all the dramatic and imaginative potential they can supply. Human issues and sentiments, such as longing or betrayal or revenge, can be framed in the context of the supernatural to produce some great gaming drama, without the Cthulhoid trope of humanity as ants whose concerns are trivial and whose existence is worthless.

As for the propriety of creating an RPG inspired by an illustrated book – well, plenty of RPGs have been inspired by comic book properties and delivered a perfectly good game. Gamers steeped in CoC shouldn’t need reminding that Clark Ashton Smith was a noted artist as well as a horror writer, and he bulks almost as big in the Cthulhu Mythos as Lovecraft himself. Johan Egerkrans, meanwhile, taps into a Scandinavian vein of folkloric and folk horror illustration almost instantly recognizable through the work of John Bauer and Theodor Kittelsen. One website devoted to troll painters lists 72 of them – more than enough to inspire many a new Vaesen scenario. Few of them outshine the artwork in Vaesen itself – the book is visually stunning to a remarkable degree, even by today’s very high RPG production standards, or Free League’s superlative track record. What’s more, the plates and illustrations are inspirational enough in themselves to fuel players’ imaginations (and nightmares).

Not that Vaesen is a totally different gaming experience. The Society whose investigations supply the successive scenarios of Vaesen recalls the Friends of Jackson Elias, Delta Green, or many another league of paranormal investigators. Castle Gyllencreutz, their base of operations with its long and varied menu of Upgrades, is a ringer for numerous headquarters of similar societies. The emphasis on Traumas and Dark Secrets in character creation will be familiar to gamers who have played Kult: Divinity Lost or Fate games. Many of the ingredients are very familiar – but they’re mixed together into a delicious and stimulating whole that doesn’t come across as stale or derivative.

For its mechanical base, Vaesen uses a fork of the Year Zero engine developed by Free League for the game of the same name. I’ve never been a huge fan of dice pool systems; but this one I know has developed a faithful following through the Alien RPG and Free League’s other properties such as the Tales from the Loop RPG, and is well tuned to Vaesen itself, with only moderate pools. There’s also the kind of fun flip you see in the PbtA games, where dice results produce all kinds of interesting and unique consequences, above all for injuries and mental damage, instead of just grinding down the hit points. Free League has been able to develop and refine the system through a succession of games, and the system in Vaesen is therefore well geared to the setting. The core book includes a comprehensive guide to structuring mysteries, with quite a few random tables for sandbox inspiration, and a single adventure, “The Dance of Dreams.”

Vaesen probably needs scenario supplements like A Wicked Secret and Other Mysteries more than many other horror RPGs, though. It’s not that the game lacks the stuff to feed a GM’s imagination. It’s that so much of the rich flavour of the setting depends on a lot of creative preparation, and the relatively simple mechanics limit the generative potential of the system in abstract. Vaesen needs a really strong, solid, well-developed, richly detailed storyline to show its best. That may be a lot of work for many GMs. Fortunately, that’s just what it gets, times four, with A Wicked Secret and Other Mysteries. The game rings the changes on locations, from the Bohuslän islands in far western Sweden to the castle town of Arensburg (modern Kuressaare) in western Estonia. As mentioned, the very detailed scenarios add further depth to the setting and its lore, and deepen the overall atmosphere. And, of course, there are fresh vaesen, in the shape of the gloson (a monstrous spectral sow) and the kraken, as well as sorcerous human adversaries.

Will I become a big Vaesen fan? I’m unlikely to play it as it stands, but I’m definitely going to plunder it for inspiration and resources for other games, and I’m delighted that it exists. Vaesen’s vaguely steampunk 19th-century frame setting could easily be ported to other game systems, and still retain much of the game’s charm. The underlying dynamic of civilization versus Nature, Reason versus inexplicable Mystery, is perennially rich in scenario potential. On the other hand, players who aren’t RPG system nerds, and just want a solid and satisfying experience out of the box, won’t be disappointed, and likely won’t feel any need to look further than the game’s basics for satisfying play. Vaesen renders its setting and its subject matter supremely well. That sounds like a pretty good definition of a good game – as opposed to a good implementation of a gaming system. I don’t know if we really are living through a new golden age of delightfully different horror games, but if we are, Vaesen is prime evidence for the thesis.

[Top]A review of Delta Green: Impossible Landscapes

Written and illustrated by Dennis Detwiller

368 pages

Published by Arc Dream, 2021

Impossible Landscapes started life as a stretch goal in Arc Dream’s original Kickstarter campaign to resurrect Delta Green as a roleplaying system and standalone game franchise in its own right. To say that it’s been eagerly anticipated is a massive understatement. Arc Dream was already responsible for Kenneth Hite’s stunning, and often revelatory, The King in Yellow – Annotated Edition (2019), and Dennis Detwiller has been lauded in RPG circles as the arch-exponent of Robert W. Chambers’ King in Yellow Mythos. As Detwiller said way back in 2015, “I created this campaign to ask – what would a full length campaign against Carcosa and the forces of madness and dissolution look like? What if, even after you escaped the Night Floors, they stayed with you? Could you escape? Can you win against madness incarnate?” And now Impossible Landscapes has finally arrived – already available in PDF, and in print from May 2021.

Just a word on Dennis Detwiller, for those who don’t already know his formidable reputation. This is the original writer, over 20 years ago, of “The Night Floors,” the seed adventure for this escapade, rated as one of the most unnerving, surreal cosmic horror RPG investigations ever penned. This is the legendary scenario designer who doesn’t believe that an adventure is complete without player-character casualties, who has put together some of the darkest, most unforgiving developments of the Cthulhu Mythos. His credo is: “Death is not only a part of Delta Green, it is its foundation,” and that “once a threat’s actions, stats and behaviors can be guessed, it is no longer frightening.” What else could you expect but an utterly brutal and unsparing roller-coaster ride?

As a physical product alone, Impossible Landscapes commands attention. It takes the cut-up aesthetic already developed in the Delta Green core books, and cranks it up to 11. The result is like the mutant offspring of a drug-fueled coupling between an Agency case file and an Edwardian occultist’s scrapbook. A few of the illustrations have appeared in previous Arc Dream products, but the plethora of new material and the unifying vision render that a quibble. I wouldn’t be surprised to see Impossible Landscapes in the Finalists listings for the Best Layout and Design and Best Art, Interior categories for the next ENnie Awards.

The content matches up to the design and presentation: no surprise, seeing as Detwiller is in charge of both. The book is divided into four major episodes or sub-campaigns: “The Night Floors,” “A Volume of Secret Faces,” “Like a Map Made of Skin,” and “The End of the World of the End.” Each of these has enough sub-modules and byways to ensure that players don’t feel too tramlined, and that no two playthroughs will likely ever follow the same trajectory. “The Night Floors” is a do-over of the original scenario, but enormously enriched in content and context. Any player who has gone through the original version needn’t fear repetition and ennui; there’s enough going on to make this a whole new experience. There are also three shorter interstitial episodes that can be used to transition major sections, but that also form further sub-adventures in themselves: “The Bookshop,” “The Missing Room, and “Hotel Broadalbin.” There are extensive handouts for the player-facing materials, supplied alongside the basic PDF.

How is it as a game, then? Well, any old-time Call of Cthulhu fan who wants tentacles and noodly appendages is going to be disappointed. This is not a monster mash, or even a body horror adventure: the horror is existential, psychological and surreal. In keeping with the book’s persistent themes, many of the menaces are automata or puppets; creatures long associated with the King in Yellow Mythos, like Byakhee, hardly put in an appearance. However, that departure from 40 years of Lovecraftian RPG tradition is exactly where Impossible Landscapes succeeds best. Not every attempt to put the King In Yellow Mythos into RPG scenario or game form has succeeded in making it genuinely unsettling: some merely succeed in making it seem quaint, or even slightly kitsch. No such worries on Detwiller’s watch. His Carcosan contamination genuinely is a creeping yellow canker on reality, whose manifestations are sometimes jaw-dropping in their insidious subversion of normality and sanity. As if Delta Green’s Sanity countdown and Bond-burning weren’t already corrosive enough, Detwiller has also introduced a new incremental mechanic, Corruption, which measures how deeply under the spell of Carcosa an Agent has fallen. That’s the kind of mechanic that definitely allows for alternative paths and approaches in the campaign: needless to say, the consequences of high Corruption are sometimes empowering, but ultimately Not Good.

Given all that’s gone before, no one should be surprised to hear that this campaign is a meat grinder. Mundane death is the least of the threats facing Agents, who are more than likely going to be either driven mad or sucked into the nightmare of Carcosa. As Detwiller points out in his introduction, “each of these four operations includes suggestions for bringing the Agents’ allies aboard as replacements for lost Agents.” It’s also one of the bleakest ever portrayals of Delta Green as an organization. Always a denizen of morally grey areas, Delta Green in all its multiple incarnations is sketched here from charcoal to deepest black: players may end up wondering if it is anything more than a manifestation of the madness it pretends to fight.

There are some issues. I’m not hugely fond of the kind of layout that refers you to stats for a creature or NPC at the end of the section, or the book, instead of close to where it appears. There are some foibles in the typesetting that may be surreal and distorting artistic invocations of the disorienting Mythos – or just layout errors. And the constant internal cross-referencing and paranoid exercises in apophenia, where names and places and numbers and generations inexplicably interrelate and reflect each other across time and space, can seem a little overdone at times, no matter how faithful a portrayal of a schizophrenic worldview they are.

There’s also, ultimately, a fundamental point about the thesis and structure of Impossible Landscapes, which may turn off some players: This is a game you can experience, but cannot win. You can survive it, and if you’re exceptionally lucky, and skillful, you might get to return to your old life more or less intact. But there’s no keeping the ultimate terror at bay, no closing Pandora’s Box. There’s a persuasive case that Delta Green, and Lovecraftian horror in general, are all about the limits of human agency when faced with the utterly inhuman – in Delta Green’s case, especially the kind of human agency that runs around shooting things and blowing things up. The protagonists in Impossible Landscapes certainly get to do plenty of that – the episodes are not structured as passive exercises in absorbing Handler exposition. There’s always plenty of choices to be made, and dice to be rolled. But none of it ultimately matters. The King in Yellow will always be on his way, today or (thanks to your actions) tomorrow, but never delayed for too long. Carcosa is always waiting to break through into mundane reality, and consume it like the sham, hollow pasteboard Potemkin fraud it has proven to be. Isn’t that the whole point, and the source of the terror, though? And even if you can’t hold back forces as inexorable as gravity or the course of the stars, the experience alone is worth the price of admission.

Impossible Landscapes takes one unsparing vision of cosmic horror about as far as it can go in RPG terms. Even the parent game, with all its frightful scenarios, doesn’t have this level of terrifying excess. Even a setting like KULT: Divinity Lost comes across in comparison as both preachy and a sop to human vanities. Perhaps some of the most appalling monstrosities in Fear Itself, or the utterly pessimistic horror of Thomas Ligotti, are the closest parallels. Impossible Landscapes over-delivers on its promise and premise by the poisonous yellow bucketful. An immediate, indispensable, classic.

[Top]A review of The Red Book of Magic

Written by Jeff Richard, Greg Stafford, Steve Perrin, and Sandy Petersen

128 pages

Published by Chaosium, 2020

According to Chaosium, The Red Book of Magic originated as a spell catalog for the yet-to-be-released title Cults of Glorantha, which quickly grew into a whole undertaking of its own. You can see why. As the Introduction says, “this book contains every Rune and spirit magic spell known at the time of publication, including many otherwise unpublished spells.” For some RuneQuest fans who have come across the complaints that many seasoned and new RuneQuest players have made about the Sorcery magic system in new-generation RuneQuest Glorantha that coverage will come as a relief. The book concentrates on the classic RuneQuest magic known since the beginnings of the system in 1978: Rune Magic, and Spirit (a.k.a. Battle) Magic. Sadly departed luminaries like Greg Stafford who authored many of the spells are therefore still referenced in the credits.

So yes, this is a lavish compendium of new and familiar spells for RuneQuest. There’s over 500 in all, along with new details on Rune metals, healing plants, illusions, and other quirks and intricacies of magical lore in Glorantha. If you already have every previous edition of RuneQuest, and every magic-related supplement ever published, do you need this book? Perhaps not, but if you didn’t pick it up out of purely instinct, you’d still be doing yourself a great disservice. Let’s leave aside the fact that this really is probably the most complete single reference book to classic RuneQuest magic around, and therefore valuable to all but the total completionist fanatic. The artwork is absolutely stunning, and easily up to the standard of the current edition of RuneQuest Glorantha. Did the artists and designers try to surpass that benchmark? I wouldn’t be surprised, because the book is a visual delight and worth owning for the pictures alone. Glorantha, and its weird and wonderful denizens, have rarely ever looked more fully realized, and more dazzling.

Then there’s the new content over and above the spell listings themselves. The sections on how the respective types of magic appear, sound, and feel are certainly going to add greatly to players’ experience when roleplaying their spell casts. Special breakouts on particular issues, such as the very powerful and common Heal Wound spell, “the most powerful healing magic available to most adventurers,” may help settle some gaming debates, and certainly help nail down key points in the entire magic system. Solid guidance on devising new spells will help grow the corpus even further.

As for the spells themselves, there’s everything from familiar standbys to the gloriously obscure and arcane. For instance, Bless Woad “can only be cast by a Wind Lord of Orlanth during the High Holy Day of Orlanth upon a properly prepared pot of woad (a blue dye derived from the woad plant), and thus can only be cast once a year.” As a practical spell, it doesn’t go very far: as a flavourful detail of setting and culture, it’s delightful.

Of course there are other RuneQuest spell books and magic-focused tomes out there, both Chaosium originals and independent productions. Simon Phipps’s Book of Doom in the Jonstown Compendium offers a claimed over 600 new spells. Nonetheless, if there’s one single must-have magic book for the RuneQuest universe, IMHO, it’s now surely this one. RuneQuest’s rebirth in the hands of Chaosium is throwing up some delightful books, and this is definitely one of them. It makes me eager to see what comes next.

[Top]A review of The Children of Fear

Written by Lynne Hardy and Friends

418 pages

Published by Chaosium, 2020

I have now gone through The Children of Fear, Chaosium’s new epic 1920s campaign for 7th Edition Call of Cthulhu, from beginning to end. I can’t claim to have read every line, let alone playtested it, so this won’t be an exhaustive review. But if you want a taste of its flavour, and its scale, now read on.

For one thing, this is not your canonical Cthulhu Mythos campaign. Rather than deploying the usual Lovecraftian panoply of Elder Gods and Great Old Ones, it draws on traditions of Mahayana and Tantric Buddhism, especially Tibetan Buddhism, and Western occultism as typified by Theosophy, and the likes of Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski and René Guénon. If I say that paintings by Nicholas Roerich pop up frequently as illustrations, that may give you an idea. The players are still on a quest to prevent the end of the world: only this time, instead of delaying the rise of R’lyeh, they’re drawn into the conflict between the eternal mystical cities of Shambhala and Agartha, as they try to forestall a premature end to the Kali Yuga.

Mythos purists may be turned off by this shift in focus, but if so, they’d be denying themselves a colossal and delirious adventure. There’s plenty of advice within the book on how to play the various entities and beings as avatars of the Elder Gods or manifestations of the Dreamlands, whether within 7th Edition CoC or Pulp Cthulhu. Ultimately, the choice is up to the players and the Keeper, and my reaction is that they’d lose an immense amount of fascinating, and frequently terrifying, detail if they tried to squeeze everything into Mythos moulds. But at the end, it’s their choice. And as a system, the 7th Edition CoC rules are fully up to the challenge.

In a campaign of this kind, ranging from China in the turbulent 1920s along the Silk Road to Tibet and colonial British India, questions of colonialism and racism, not to mention cultural appropriation, are almost sure to arise. All I can say is that Lynne Hardy and her fellow writers have done an extremely sensitive, painstaking, respectful and even reverential exploration of the traditions and cultures involved, even when they’ve turned a dark mirror to some of their most alarming aspects to create the villains of the piece. Almost every creed or social fabric is presented on its own terms, whether the strictures of the Hindu caste system, or the extremes of Tibetan Bon lore – in authentic terms that nonetheless will at times push your Culture Shock meter up to 11. Racism in the British colonial context is presented unflinchingly, with no attempt to handwave or airbrush over its impact on the campaign. Players will definitely encounter seriously adult content, sexual as well as horrific, but that is suitably signposted, with plenty of warnings for Keepers to secure player buy-in and ensure that no one’s consent to participate in such sections is overruled.

With those concerns covered, how about the meat of the mission? I’ve already mentioned what an incredible odyssey this is through different mythologies and belief-systems. Players will encounter creatures and situations that will likely stun and bewilder them, as well as just challenging them to all kinds of contests of brain and brawn. There’s plenty of menaces and dangers along the way, including a particularly nasty pursuing cult. Disorienting dreams, visions and premonitions also form a major strand in the narrative. Canonical Mythos monsters like white apes and Mi-go do crop up from time to time, but never in a way to throw off the central thread of the story, and always without compromising its mythological tenets. The political and military complications of the period also form a significant aspect of the play, and once again, game groups who want to skip those in favour of the purely supernatural and Unnatural will be missing a lot. In fact, the historical flavour of the campaign, in each of its different locations, is as thick and dense as a cup of Tibetan yak butter tea.

As for the physical quality of the book and all its handouts and maps, it looks to me like a new high in Chaosium’s current, brilliant spate of high-quality design and art direction. The illustrations range from Roerich to exquisitely detailed reproductions of Victorian aquatints. The maps immediately tempt you to dive into the locations and start drawing out all kinds of byways and homebrewed adventures. The players are gifted with a plethora of handouts, all beautifully designed and produced. Even a fantastic job of book production like the updated 7th edition Masks of Nyarlathotep rather tends to fade into the background in comparison with The Children of Fear.

As it happens, I get that impression from more than just the art. The Children of Fear won’t work for playgroups who want their campaigns light on detail but heavy on thrills and spills. But for anyone who wants a historically detailed and hugely varied adventure that pushes you right up against the weirdness and mystery of the human spirit without needing to dive into genre horror to do so, this is a gem and an instant classic. The prospect of pairing it with a similarly accurate depiction of period China like Sons of the Singularity’s The Sassoon Files gets my mouth watering. Players could wander through this campaign for years and still not come to the end of it; and very probably they wouldn’t want to leave. Unreservedly recommended.

[Top]A review of Apocthulhu

Written by Christopher Smith Adair, Fred Behrendt, Chad Bowser, Dean Engelhardt, Jo Kreil, Jeff Moeller, Emily O’Neil, Kevin Ross and Dave Sokolowski, from Cthulhu Reborn

What will happen when the stars do come right? That’s a question that has hung over Lovecraftian fiction practically ever since HPL laid down his pen at the end of “The Call of Cthulhu,” and that has haunted Lovecraftian gaming ever since Sandy Petersen’s first dips into the realms of non-Euclidean dicerolling. What will happen when Great Cthulhu does rise from the depths, or when the Whateleys finally open the gate to Yog-Sothoth and cleanse Earth life off the planet, or whatever other version of the End Times is in the fiction? Attempts to answer that question in a gaming context include Pelgrane Press’s Cthulhu Apocalypse, Evil Hat’s very wonderful Fate-based Fate of Cthulhu, and now Cthulhu Reborn’s Apocthulhu.

Australian RPG indie publisher Cthulhu Reborn was hitherto chiefly an archive site “providing a home for professional-looking typeset renditions of old, classic, and best of all free ‘Call of Cthulhu’ scenarios” released under Creative Commons licenses, so it’s not surprising that the book has made best use of publicly usable Lovecraftian gaming materials. (Their previous title Convicts & Cthulhu, transporting [sic.] Lovecraftian horror to early colonial Australia, has been recognized as “a historically- and culturally-significant publication by the National Library of Australia.”) The system in Apocthulhu has been almost entirely pieced together by Cthulhu Reborn’s Dean Engelhardt from existing D100 OGL material, very close to what was done for Arc Dream’s updating of the Delta Green platform. Indeed, strong hints of Delta Green recur often in the system, such as its use of personal Bonds as important pillars in a character’s losing struggle against the sanity-shattering impact of the Great Old Ones. That’s no bad thing, as Arc Dream-vintage Delta Green benefits from one of the leanest and most elegant investigative RPG systems around – one directly compatible, furthermore, with decades of BRP and d100 content for other systems, including material for Call of Cthulhu 6th and earlier editions. Apocthulhu’s mechanics are straightforward, well-tried, familiar to anyone who’s played in this genre, and occupy a relatively small proportion of the book, leaving most of its 330 pages for lavish setting detail.

Apocthulhu has inherited many of the virtues of its predecessors, yet still manages to stand apart from both Delta Green and Call of Cthulhu old and new, and be very much its own animal. For instance, the designers have put a lot of thought and work into creating a convincing resources and scavenging system for the post-apocalyptic hellscape, reminiscent if anything of the foraging mechanisms of the Fallout franchise. Potential “career” paths for survivors of the apocalypse are presented with varying levels of experience and depredation, depending on the severity of the disaster and the number of years since it befell Mankind. And rather than come up with yet another Lovecraftian bestiary, the authors have directed readers to the many that do exist, and instead whipped up eight sample apocalypses and three full scenarios, each with its own particular flavour of terror. Some of these are Mythos catastrophes involving canonical deities, or even hints dropped in some of Lovecraftian gaming’s most celebrated campaigns; others are entirely original with fresh-baked sets of very alarming horrors that more than make up for the absence of a standalone bestiary. Indeed, the game could easily be used as it stands to build a Walking Dead RPG, or to play any other non-Lovecraftian apocalyptic scenario. In a long and honourable lineage of post-apocalyptic RPGs from Gamma World onwards, Apocthulhu stands out for its grittiness and grimness, as well as for comfortably straddling the divide between Lovecraftian dread and other forms of horror.

One of its best tricks is saved, almost, for last. Apocthulhu has full d100-compatible rules for playing William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, in the longest and most detailed of its scenario settings, by Kevin Ross, which almost stands alone as a separate vehicle. Hodgson’s immensely distant sunless dreamscape, ruled by nightmare presences that besiege humanity’s last redoubt, was a formative influence on Lovecraft, but has remained very underused by RPG designers, no least because of the original novel’s turgid prose. Consequently, Apocthulhu and Kevin Ross are performing a real service to the horror RPG audience by disinterring Hodgson’s creations and framing them in such a well-proven, flexible system. Ross has said in one interview that the Night Land section is due to be expanded into a full-on standalone fork of the system, and that can’t come soon enough.

The overall standard of design and artwork for Apocthulhu is exceptionally high. Yes, there’s some style choices I may not agree with, and not every illustration is to my taste, but overall it’s at least as good-looking a book as anything you’d see from the top-line RPG majors these days. Apocthulhu is a testament to the quality and strength that modern indie game publishers can achieve in both form and content, and is likely to become many gamers’ choice for any kind of post-apocalyptic gaming, let alone Lovecraftian. You can plug it into reams of other existing games and game systems, or just ring the changes on the many options it provides by itself. The game has just gone live as a PDF on DriveThruRPG, with the print version being finalized as we speak, and you are warmly advised to snap it up. The stars couldn’t be righter.

[Top]A review of Malleus Monstrorum: Cthulhu Mythos Bestiary, by Mike Mason and Scott David Aniolowski, with Paul Fricker

Originally published in 2006, Malleus Monstrorum followed the tradition of S. Petersen’s Field Guide to Cthulhu Monsters (1988) in bringing the D&D Monster Manual and Fiend Folio approach to the Cthulhu Mythos. Chaosium has now doubled down on the great tradition of Call of Cthulhu monsters and malevolences: literally, since this is in two volumes. It’s certainly sumptuous. The slipcased two-volume hardcover edition is $89.99; the PDF is $39.99. There’s also a special leatherette hard-cover edition for all of $199.99. The cover and interior art by Loïc Muzy is literally mind-blowing, and the larger colour plates are superb.

There’s no questioning the compendiousness of the volume. You can see on the credits and copyrights page the extent to which the authors have ransacked the estates of various Cthulhu Mythos writers – Eddy C. Bertin, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Walter C. DeBill, August Derleth, Robert E. Howard, T.E.D. Klein, Henry Kuttner, Brian Lumley, Gary C. Myers, Richard F. Searight, Clark Ashton Smith, Donald Wandrei, Colin Wilson – to reframe just about all of their creations as CoC creatures. Every variation on more or less canonical creatures and divine beings is rung.

All this is a summary of the new edition’s many excellences. Those are self-evident, and any problem I have with its approach is purely personal. All the same, I do have very specific issues with it.

For one thing, there’s a certain schizophrenia in its approach. The introductory essays give extensive advice to Keepers on presenting Mythos creatures ambiguously, ringing the changes on their descriptions, ideally never referring to them directly by name unless you want to skip over them with as little time and trouble as possible. Yet you have umpteen specific, concrete articulations of the monsters in the most concrete terms, exhaustively particularized. Is that going to boost Keepers’ imaginations, or channel and tramline them?

Then there’s the more than a little gung-ho approach to Mythos deities and demigods. For some historical perspective on this, way back in an interview with Different Worlds magazine in February 1982, Sandy Petersen talked about the design process behind the original Call of Cthulhu: “At first, I tried to simply write up all the different deities as if they were normal monsters, listing SIZ, POW, and so forth for each different god, along with some brief notes about the cult, if any, of that particular being. I quickly discovered that this approach was unsuitable, since the scores I gave the various monster gods was too completely arbitrary, and the possibility of harming one in the course of play too remote for their statistics to really matter… I listed each god according to its effects when summoned, its characteristics, its worshipers, and the gifts or requirements that it demanded of those worshipers. This approach was eminently workable, and I was quite self-satisfied at its conclusion. Later on in the development of the book, Steve Perrin wanted to re-include the statistics for the deities, and thus the STR, INT, etc. of Cthulhu and the rest are now included in the game again.”

I side with Sandy Petersen on this one. Not only is the prospect of damaging a god just a little bit ridiculous in any context, it absolutely goes against the core Lovecraftian thesis that humanity is less than ants before utterly powerful and incomprehensible deities. Call of Cthulhu, needless to say, does not implement that line of thinking in its system, and Malleus Monstrorum definitely doesn’t. For instance, “Mythos deities are not (in the main) omnipotent.” That isn’t exactly the impression that one gets from Lovecraft’s descriptions of Azathoth, or even hints about Yog-Sothoth. “If hand-to-hand melee with an Old One is what you are going for, then cool – this is your game, so go for it.” Well fine, except that your game is likely to be lacking in both Lovecraftian and horror – something of a problem with a game of Lovecraftian horror. Petersen said about Call of Cthulhu in the same interview, “in the game’s present form, it plays much like an adventure mystery, such as the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark.” Nothing wrong with that, except that it misses out so much of what made Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos so unique and so genuinely terrifying.

The hobby has grown a lot since the early days of Call of Cthulhu and Petersen’s interview, with a whole raft of different approaches and styles. Despite its seven reiterations, I’m not sure that Call of Cthulhu itself has grown all the way with it. Mythos gaming has grown out and ramified in all kinds of directions from its original CoC roots, but Malleus Monstrorum doesn’t seem to have fallen far from the tree. And I wonder if this is going to leave Chaosium with an audience burnout problem, where players take up the game in a flush of adolescent enthusiasm, then drop it later because it has only limited room to grow up with them. Other RPGs, not least Delta Green, are as adult as they come, and supported by robust fan bases. For me at least, Call of Cthulhu still looks to be ploughing the (admittedly well-worn and well-tried) furrow of monster-bashing, and going monstrously monstrous on monster adversaries with a monster volume of material. Powergaming, levelling-up, minmaxing and twinking has worked well enough for D&D, after all, so why not keep pushing those same approaches For those players who game to indulge their wish-fulfilment power fantasies, Malleus Monstrorum provides whole gods that you can squash.

Of course there’s probably a bit of that kind of player in all RPGers, but there are other styles of play too, and powergaming is particularly jarring in a genre that is supposed to be about helplessness. I mean, one of the prime attractions of Call of Cthulhu was supposed to be that the more you encountered the Mythos and its creatures, the more deranged and hence helpless you became. Yet a big target HP total for a god makes it just another end level boss to bash with a bigger bashy thing. Face it, hit point stats are there so you can hit things and grind up. Hitting gods may work in D&D, but it’s hardly recommended in most other less powergaming-focused systems. If you can hit something, you can kill it: ergo, it’s only scary to a certain extent. Lovecraft’s deities and demigods suffered from no such limitation.

Also, look at the sheer crunchiness of Malleus Monstrorum. It’s all compendious stats and detail. So many RPGs now are launched as rules-lite in one form or another, including many independent Cthulhu hacks. Delta Green’s essential system rules run to just 96 pages. Fate Condensed runs to just 68 pages; The Cthulhu Hack runs to 52 pages. And One Page Cthulhu is… well. Yet, CoC’s DNA is solid BRP, just like Delta Green. It just goes to show the different ways things can go.

My feeling is that, if a large slice of the RPG community has moved away from stats-intensive, crunch-heavy systems, it’s for a good reason. But for those whose appetite for sheer crunch hasn’t been satisfied by Warhammer 40,000, we have in 7th edition Call of Cthulhu 288 pages of Investigator Handbook and 448 pages of Keeper Rulebook. And yes, 480 pages of Malleus Monstrorum.

H.P. Lovecraft himself wrote: “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” But in Malleus Monstrorum, everything is known, known: ground out in stats right down to most exhaustive, exhausting, tiresome detail. Where’s the mystery, the fear, in that? Azathoth has 500 POW, wow! That’s really Powerful! Like, that means that you actually need 50 average human magic practitioners to equal the Demon Sultan principle of all Creation and embodiment of all the forces of the entire Universe. Feel strong, you 50 dudes! And this is supposed to be the world’s Number One horror RPG.

Look at the alternative approach in Trail of Cthulhu: “we have included only two statistics for gods and titans, the additional Stability loss and Sanity loss suffered when they are encountered… Everything else is and should be entirely arbitrary and immense. Fighting a Great Old One is like fighting an artillery barrage. It doesn’t matter how many shotguns you brought.” Sure, the introduction to Malleus Monstrorum also states that: “the Cthulhu Mythos is unknowable to humanity. What scraps of information are known are drawn from rare and fragmentary texts, conversations with wizards and witches, and from life-altering exposure… What “canon” exists is loose and unreliable.” Yet that declaration seems to be working at the very least at cross purposes with the actual contents of the book. There’s an awful lot of very emphatic stats and numbers for stuff that is supposed to be so unknowable. And ultimately players are likely to be most guided by the mechanics.

Chaosium’s recent revival has produced some truly fantastic Call of Cthulhu products: Berlin – The Wicked City springs to mind; or Harlem Unbound. And there’s no denying the sheer material quality of their current reborn product range. But I do have big reservations about a large slice of their approach, and Malleus Monstrorum exemplifies those reservations. For me, it succeeds in being at once both overpowering and underwhelming. Its sheer physical quality, and quantity, masks significant conceptual shortcomings. It’s the Super Size big-box belly-filler for an audience whose tastes have grown a lot more diverse and sophisticated. Sometimes more really is less.

That said, anyone like me who enjoys a lower-key, more complex and nuanced approach to their RPGs has got to face up to one thing with Lovecraft: Is he more famous for his philosophy of pessimistic cosmicism, or for the monsters he created? I doubt he’d have anything like the name brand recognition, or the long tail of RPGs following on his legacy, if it wasn’t for tentacular Cthulhu and all the other creatures he used to embody his fears. Perhaps it’s unfair to beat Malleus Monstrorum up for an issue that starts with the author himself.

Anyway, that’s Malleus Monstrorum for you. It doesn’t incorporate much of the new narrativist developments in RPGs. It pushes the original, traditional, simulationist approach, and 1980s attitude to monsters and challenges, just about as far as it can go. So long as you’re happy with those limitations, this is as good as it can possibly get.

[Top]