A review of Vaesen: Nordic Horror Roleplaying, and Vaesen: A Wicked Secret and Other Mysteries

Illustration and original concept by Johan Egerkrans, writing by Nils Hintze and others

240 pages / 112 pages

Published by Free League (Fria Ligan), 2020

I won’t add to the many laudatory reviews of Vaesen from Sweden’s Free League (Fria Ligan) by just doing a straight runthrough of its qualities as an RPG. Rather, I want to use the game to pick a personal bone with the RPG horror landscape as it stands. It’s the bone that pulled me into RPG writing in the first place. So if the following review seems egocentric, I’m sorry; but Vaesen really doesn’t need me to speak for it – it can more than make a case for itself.

For a start, the game – inspired by and substantially created by the Swedish fantasy illustrator and author Johan Egerkrans – could well have been subtitled “Nordic Folk Horror Roleplaying,” and that’s all to its credit. For the purposes of this review, I could dub it “Trembling Without Tentacles.” When I wrote my first horror RPG, I did it substantially because I was fed up with the Lovecrafting of horror gaming, where every pantheon and every legendary being was warped into a manifestation of the Great Old Ones. Call of Cthulhu saturates horror gaming, or at least did so before the recent wave of indie RPGs, and the advent of Powered by the Apocalypse and the alternative rule systems typified by both the OSR movement and the minimalist “tiny” rulesets. For too long, Call of Cthulhu was the monocrop that cut out all other species of horror game from the light. I’ve had more than one horror RPG podcast recently remind me that Call of Cthulhu got to the table first, right at the start of the hobby, and has buttressed its position with reams of high-quality scenarios and campaigns, so that GMs and players need little added effort to immerse themselves in it and it alone for years on end.

That’s all well and good, except that horror gaming has so much more to offer than just tentacles and existential terror. Look, for instance, at the success of Monster of the Week, or Monsterhearts, or Alien, as very different takes on the horror genre that bring fresh and very enjoyable experiences to the gaming table. Look at the immense troves of fascinating material in the world’s folk cultures and traditions – all of which get distorted and bowdlerized as soon as they’re tapped for Call of Cthulhu gaming, into manifestations of Nyarlathotep and miscategorized Deep Ones. Look at ghost stories and psychic investigations, which get very thin coverage from Lovecraft (perhaps because of his nihilistic materialism), but which nonetheless are the very stuff of horror, and rich in potential for RPGs. When I wrote Casting the Runes, I did it exactly because Lovecraft’s legacy to gaming was cutting out or trivializing the great tradition of ghost stories that Lovecraft himself revered in his own critical writing. Look at all the different kinds of horror story that are totally unlike Lovecraft’s own vision of cosmic nihilism. It’s no wonder that Call of Cthulhu proved to be a superb base for some great board games when the underlying narrative thrust of so many Mythos stories is so repetitive and predictable.

So it’s great to embrace a game whose strengths are all about traditions utterly removed from Lovecraftian horror. Instead, Vaesen dives headlong into Scandinavia’s rich heritage of legendary beings, and comes up smelling all the fresher for it. The titular vaesen (supernatural beings) are described in loving detail, with 21 fully covered and more than enough guidance to create more based on the included templates. Each has its own unique Powers, and Conditions that kick in as the creature is stressed during conflict – for instance, the Ash Tree Wife dissolves into ash leaves when it’s defeated, while a Brook Horse can lure or grab a victim in its teeth and drag them off for a mad brook ride. The mid-Victorian, vaguely steampunk Scandinavian setting is not only flavourful, it also supports the trope of modernity versus tradition which is one of the game’s major themes. A game which unapologetically presents folklore and established traditions, instead of jamming everything into the Lovecraftian cookie-cutter, not only has the attraction of new and interesting creatures to face, but also allows for a slew of different flavours of stories and themes. Instead of devolving to the persistent Cthulhu Mythos tropes of cosmic horror and an indifferent, malignant underlying reality, players of Vaesen can tackle threats no less menacing but with a whole different range of emotional registers. You don’t often get pathos from the loss or the defeat of the inexplicable in Call of Cthulhu and its ilk, but such topics spring up naturally in Vaesen. Both Christianity and Norse paganism can be brought to the gaming table in full, for all the dramatic and imaginative potential they can supply. Human issues and sentiments, such as longing or betrayal or revenge, can be framed in the context of the supernatural to produce some great gaming drama, without the Cthulhoid trope of humanity as ants whose concerns are trivial and whose existence is worthless.

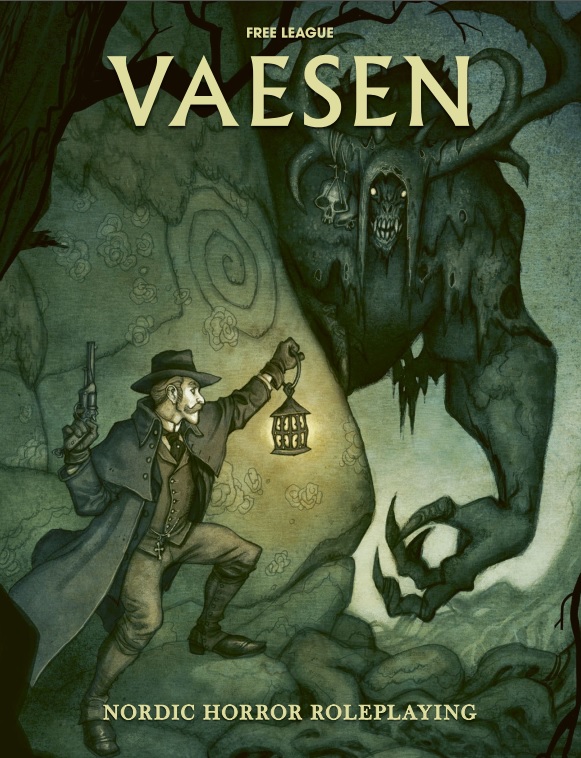

As for the propriety of creating an RPG inspired by an illustrated book – well, plenty of RPGs have been inspired by comic book properties and delivered a perfectly good game. Gamers steeped in CoC shouldn’t need reminding that Clark Ashton Smith was a noted artist as well as a horror writer, and he bulks almost as big in the Cthulhu Mythos as Lovecraft himself. Johan Egerkrans, meanwhile, taps into a Scandinavian vein of folkloric and folk horror illustration almost instantly recognizable through the work of John Bauer and Theodor Kittelsen. One website devoted to troll painters lists 72 of them – more than enough to inspire many a new Vaesen scenario. Few of them outshine the artwork in Vaesen itself – the book is visually stunning to a remarkable degree, even by today’s very high RPG production standards, or Free League’s superlative track record. What’s more, the plates and illustrations are inspirational enough in themselves to fuel players’ imaginations (and nightmares).

Not that Vaesen is a totally different gaming experience. The Society whose investigations supply the successive scenarios of Vaesen recalls the Friends of Jackson Elias, Delta Green, or many another league of paranormal investigators. Castle Gyllencreutz, their base of operations with its long and varied menu of Upgrades, is a ringer for numerous headquarters of similar societies. The emphasis on Traumas and Dark Secrets in character creation will be familiar to gamers who have played Kult: Divinity Lost or Fate games. Many of the ingredients are very familiar – but they’re mixed together into a delicious and stimulating whole that doesn’t come across as stale or derivative.

For its mechanical base, Vaesen uses a fork of the Year Zero engine developed by Free League for the game of the same name. I’ve never been a huge fan of dice pool systems; but this one I know has developed a faithful following through the Alien RPG and Free League’s other properties such as the Tales from the Loop RPG, and is well tuned to Vaesen itself, with only moderate pools. There’s also the kind of fun flip you see in the PbtA games, where dice results produce all kinds of interesting and unique consequences, above all for injuries and mental damage, instead of just grinding down the hit points. Free League has been able to develop and refine the system through a succession of games, and the system in Vaesen is therefore well geared to the setting. The core book includes a comprehensive guide to structuring mysteries, with quite a few random tables for sandbox inspiration, and a single adventure, “The Dance of Dreams.”

Vaesen probably needs scenario supplements like A Wicked Secret and Other Mysteries more than many other horror RPGs, though. It’s not that the game lacks the stuff to feed a GM’s imagination. It’s that so much of the rich flavour of the setting depends on a lot of creative preparation, and the relatively simple mechanics limit the generative potential of the system in abstract. Vaesen needs a really strong, solid, well-developed, richly detailed storyline to show its best. That may be a lot of work for many GMs. Fortunately, that’s just what it gets, times four, with A Wicked Secret and Other Mysteries. The game rings the changes on locations, from the Bohuslän islands in far western Sweden to the castle town of Arensburg (modern Kuressaare) in western Estonia. As mentioned, the very detailed scenarios add further depth to the setting and its lore, and deepen the overall atmosphere. And, of course, there are fresh vaesen, in the shape of the gloson (a monstrous spectral sow) and the kraken, as well as sorcerous human adversaries.

Will I become a big Vaesen fan? I’m unlikely to play it as it stands, but I’m definitely going to plunder it for inspiration and resources for other games, and I’m delighted that it exists. Vaesen’s vaguely steampunk 19th-century frame setting could easily be ported to other game systems, and still retain much of the game’s charm. The underlying dynamic of civilization versus Nature, Reason versus inexplicable Mystery, is perennially rich in scenario potential. On the other hand, players who aren’t RPG system nerds, and just want a solid and satisfying experience out of the box, won’t be disappointed, and likely won’t feel any need to look further than the game’s basics for satisfying play. Vaesen renders its setting and its subject matter supremely well. That sounds like a pretty good definition of a good game – as opposed to a good implementation of a gaming system. I don’t know if we really are living through a new golden age of delightfully different horror games, but if we are, Vaesen is prime evidence for the thesis.