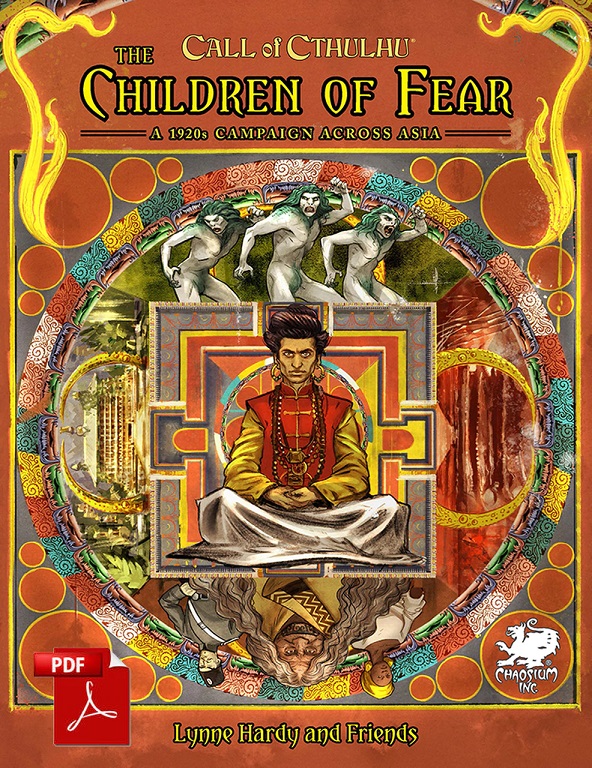

A review of The Children of Fear

Written by Lynne Hardy and Friends

418 pages

Published by Chaosium, 2020

I have now gone through The Children of Fear, Chaosium’s new epic 1920s campaign for 7th Edition Call of Cthulhu, from beginning to end. I can’t claim to have read every line, let alone playtested it, so this won’t be an exhaustive review. But if you want a taste of its flavour, and its scale, now read on.

For one thing, this is not your canonical Cthulhu Mythos campaign. Rather than deploying the usual Lovecraftian panoply of Elder Gods and Great Old Ones, it draws on traditions of Mahayana and Tantric Buddhism, especially Tibetan Buddhism, and Western occultism as typified by Theosophy, and the likes of Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski and René Guénon. If I say that paintings by Nicholas Roerich pop up frequently as illustrations, that may give you an idea. The players are still on a quest to prevent the end of the world: only this time, instead of delaying the rise of R’lyeh, they’re drawn into the conflict between the eternal mystical cities of Shambhala and Agartha, as they try to forestall a premature end to the Kali Yuga.

Mythos purists may be turned off by this shift in focus, but if so, they’d be denying themselves a colossal and delirious adventure. There’s plenty of advice within the book on how to play the various entities and beings as avatars of the Elder Gods or manifestations of the Dreamlands, whether within 7th Edition CoC or Pulp Cthulhu. Ultimately, the choice is up to the players and the Keeper, and my reaction is that they’d lose an immense amount of fascinating, and frequently terrifying, detail if they tried to squeeze everything into Mythos moulds. But at the end, it’s their choice. And as a system, the 7th Edition CoC rules are fully up to the challenge.

In a campaign of this kind, ranging from China in the turbulent 1920s along the Silk Road to Tibet and colonial British India, questions of colonialism and racism, not to mention cultural appropriation, are almost sure to arise. All I can say is that Lynne Hardy and her fellow writers have done an extremely sensitive, painstaking, respectful and even reverential exploration of the traditions and cultures involved, even when they’ve turned a dark mirror to some of their most alarming aspects to create the villains of the piece. Almost every creed or social fabric is presented on its own terms, whether the strictures of the Hindu caste system, or the extremes of Tibetan Bon lore – in authentic terms that nonetheless will at times push your Culture Shock meter up to 11. Racism in the British colonial context is presented unflinchingly, with no attempt to handwave or airbrush over its impact on the campaign. Players will definitely encounter seriously adult content, sexual as well as horrific, but that is suitably signposted, with plenty of warnings for Keepers to secure player buy-in and ensure that no one’s consent to participate in such sections is overruled.

With those concerns covered, how about the meat of the mission? I’ve already mentioned what an incredible odyssey this is through different mythologies and belief-systems. Players will encounter creatures and situations that will likely stun and bewilder them, as well as just challenging them to all kinds of contests of brain and brawn. There’s plenty of menaces and dangers along the way, including a particularly nasty pursuing cult. Disorienting dreams, visions and premonitions also form a major strand in the narrative. Canonical Mythos monsters like white apes and Mi-go do crop up from time to time, but never in a way to throw off the central thread of the story, and always without compromising its mythological tenets. The political and military complications of the period also form a significant aspect of the play, and once again, game groups who want to skip those in favour of the purely supernatural and Unnatural will be missing a lot. In fact, the historical flavour of the campaign, in each of its different locations, is as thick and dense as a cup of Tibetan yak butter tea.

As for the physical quality of the book and all its handouts and maps, it looks to me like a new high in Chaosium’s current, brilliant spate of high-quality design and art direction. The illustrations range from Roerich to exquisitely detailed reproductions of Victorian aquatints. The maps immediately tempt you to dive into the locations and start drawing out all kinds of byways and homebrewed adventures. The players are gifted with a plethora of handouts, all beautifully designed and produced. Even a fantastic job of book production like the updated 7th edition Masks of Nyarlathotep rather tends to fade into the background in comparison with The Children of Fear.

As it happens, I get that impression from more than just the art. The Children of Fear won’t work for playgroups who want their campaigns light on detail but heavy on thrills and spills. But for anyone who wants a historically detailed and hugely varied adventure that pushes you right up against the weirdness and mystery of the human spirit without needing to dive into genre horror to do so, this is a gem and an instant classic. The prospect of pairing it with a similarly accurate depiction of period China like Sons of the Singularity’s The Sassoon Files gets my mouth watering. Players could wander through this campaign for years and still not come to the end of it; and very probably they wouldn’t want to leave. Unreservedly recommended.