A review of The Red Book of Magic

Written by Jeff Richard, Greg Stafford, Steve Perrin, and Sandy Petersen

128 pages

Published by Chaosium, 2020

According to Chaosium, The Red Book of Magic originated as a spell catalog for the yet-to-be-released title Cults of Glorantha, which quickly grew into a whole undertaking of its own. You can see why. As the Introduction says, “this book contains every Rune and spirit magic spell known at the time of publication, including many otherwise unpublished spells.” For some RuneQuest fans who have come across the complaints that many seasoned and new RuneQuest players have made about the Sorcery magic system in new-generation RuneQuest Glorantha that coverage will come as a relief. The book concentrates on the classic RuneQuest magic known since the beginnings of the system in 1978: Rune Magic, and Spirit (a.k.a. Battle) Magic. Sadly departed luminaries like Greg Stafford who authored many of the spells are therefore still referenced in the credits.

So yes, this is a lavish compendium of new and familiar spells for RuneQuest. There’s over 500 in all, along with new details on Rune metals, healing plants, illusions, and other quirks and intricacies of magical lore in Glorantha. If you already have every previous edition of RuneQuest, and every magic-related supplement ever published, do you need this book? Perhaps not, but if you didn’t pick it up out of purely instinct, you’d still be doing yourself a great disservice. Let’s leave aside the fact that this really is probably the most complete single reference book to classic RuneQuest magic around, and therefore valuable to all but the total completionist fanatic. The artwork is absolutely stunning, and easily up to the standard of the current edition of RuneQuest Glorantha. Did the artists and designers try to surpass that benchmark? I wouldn’t be surprised, because the book is a visual delight and worth owning for the pictures alone. Glorantha, and its weird and wonderful denizens, have rarely ever looked more fully realized, and more dazzling.

Then there’s the new content over and above the spell listings themselves. The sections on how the respective types of magic appear, sound, and feel are certainly going to add greatly to players’ experience when roleplaying their spell casts. Special breakouts on particular issues, such as the very powerful and common Heal Wound spell, “the most powerful healing magic available to most adventurers,” may help settle some gaming debates, and certainly help nail down key points in the entire magic system. Solid guidance on devising new spells will help grow the corpus even further.

As for the spells themselves, there’s everything from familiar standbys to the gloriously obscure and arcane. For instance, Bless Woad “can only be cast by a Wind Lord of Orlanth during the High Holy Day of Orlanth upon a properly prepared pot of woad (a blue dye derived from the woad plant), and thus can only be cast once a year.” As a practical spell, it doesn’t go very far: as a flavourful detail of setting and culture, it’s delightful.

Of course there are other RuneQuest spell books and magic-focused tomes out there, both Chaosium originals and independent productions. Simon Phipps’s Book of Doom in the Jonstown Compendium offers a claimed over 600 new spells. Nonetheless, if there’s one single must-have magic book for the RuneQuest universe, IMHO, it’s now surely this one. RuneQuest’s rebirth in the hands of Chaosium is throwing up some delightful books, and this is definitely one of them. It makes me eager to see what comes next.

A review of The Children of Fear

Written by Lynne Hardy and Friends

418 pages

Published by Chaosium, 2020

I have now gone through The Children of Fear, Chaosium’s new epic 1920s campaign for 7th Edition Call of Cthulhu, from beginning to end. I can’t claim to have read every line, let alone playtested it, so this won’t be an exhaustive review. But if you want a taste of its flavour, and its scale, now read on.

For one thing, this is not your canonical Cthulhu Mythos campaign. Rather than deploying the usual Lovecraftian panoply of Elder Gods and Great Old Ones, it draws on traditions of Mahayana and Tantric Buddhism, especially Tibetan Buddhism, and Western occultism as typified by Theosophy, and the likes of Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski and René Guénon. If I say that paintings by Nicholas Roerich pop up frequently as illustrations, that may give you an idea. The players are still on a quest to prevent the end of the world: only this time, instead of delaying the rise of R’lyeh, they’re drawn into the conflict between the eternal mystical cities of Shambhala and Agartha, as they try to forestall a premature end to the Kali Yuga.

Mythos purists may be turned off by this shift in focus, but if so, they’d be denying themselves a colossal and delirious adventure. There’s plenty of advice within the book on how to play the various entities and beings as avatars of the Elder Gods or manifestations of the Dreamlands, whether within 7th Edition CoC or Pulp Cthulhu. Ultimately, the choice is up to the players and the Keeper, and my reaction is that they’d lose an immense amount of fascinating, and frequently terrifying, detail if they tried to squeeze everything into Mythos moulds. But at the end, it’s their choice. And as a system, the 7th Edition CoC rules are fully up to the challenge.

In a campaign of this kind, ranging from China in the turbulent 1920s along the Silk Road to Tibet and colonial British India, questions of colonialism and racism, not to mention cultural appropriation, are almost sure to arise. All I can say is that Lynne Hardy and her fellow writers have done an extremely sensitive, painstaking, respectful and even reverential exploration of the traditions and cultures involved, even when they’ve turned a dark mirror to some of their most alarming aspects to create the villains of the piece. Almost every creed or social fabric is presented on its own terms, whether the strictures of the Hindu caste system, or the extremes of Tibetan Bon lore – in authentic terms that nonetheless will at times push your Culture Shock meter up to 11. Racism in the British colonial context is presented unflinchingly, with no attempt to handwave or airbrush over its impact on the campaign. Players will definitely encounter seriously adult content, sexual as well as horrific, but that is suitably signposted, with plenty of warnings for Keepers to secure player buy-in and ensure that no one’s consent to participate in such sections is overruled.

With those concerns covered, how about the meat of the mission? I’ve already mentioned what an incredible odyssey this is through different mythologies and belief-systems. Players will encounter creatures and situations that will likely stun and bewilder them, as well as just challenging them to all kinds of contests of brain and brawn. There’s plenty of menaces and dangers along the way, including a particularly nasty pursuing cult. Disorienting dreams, visions and premonitions also form a major strand in the narrative. Canonical Mythos monsters like white apes and Mi-go do crop up from time to time, but never in a way to throw off the central thread of the story, and always without compromising its mythological tenets. The political and military complications of the period also form a significant aspect of the play, and once again, game groups who want to skip those in favour of the purely supernatural and Unnatural will be missing a lot. In fact, the historical flavour of the campaign, in each of its different locations, is as thick and dense as a cup of Tibetan yak butter tea.

As for the physical quality of the book and all its handouts and maps, it looks to me like a new high in Chaosium’s current, brilliant spate of high-quality design and art direction. The illustrations range from Roerich to exquisitely detailed reproductions of Victorian aquatints. The maps immediately tempt you to dive into the locations and start drawing out all kinds of byways and homebrewed adventures. The players are gifted with a plethora of handouts, all beautifully designed and produced. Even a fantastic job of book production like the updated 7th edition Masks of Nyarlathotep rather tends to fade into the background in comparison with The Children of Fear.

As it happens, I get that impression from more than just the art. The Children of Fear won’t work for playgroups who want their campaigns light on detail but heavy on thrills and spills. But for anyone who wants a historically detailed and hugely varied adventure that pushes you right up against the weirdness and mystery of the human spirit without needing to dive into genre horror to do so, this is a gem and an instant classic. The prospect of pairing it with a similarly accurate depiction of period China like Sons of the Singularity’s The Sassoon Files gets my mouth watering. Players could wander through this campaign for years and still not come to the end of it; and very probably they wouldn’t want to leave. Unreservedly recommended.

[Top]A review of Apocthulhu

Written by Christopher Smith Adair, Fred Behrendt, Chad Bowser, Dean Engelhardt, Jo Kreil, Jeff Moeller, Emily O’Neil, Kevin Ross and Dave Sokolowski, from Cthulhu Reborn

What will happen when the stars do come right? That’s a question that has hung over Lovecraftian fiction practically ever since HPL laid down his pen at the end of “The Call of Cthulhu,” and that has haunted Lovecraftian gaming ever since Sandy Petersen’s first dips into the realms of non-Euclidean dicerolling. What will happen when Great Cthulhu does rise from the depths, or when the Whateleys finally open the gate to Yog-Sothoth and cleanse Earth life off the planet, or whatever other version of the End Times is in the fiction? Attempts to answer that question in a gaming context include Pelgrane Press’s Cthulhu Apocalypse, Evil Hat’s very wonderful Fate-based Fate of Cthulhu, and now Cthulhu Reborn’s Apocthulhu.

Australian RPG indie publisher Cthulhu Reborn was hitherto chiefly an archive site “providing a home for professional-looking typeset renditions of old, classic, and best of all free ‘Call of Cthulhu’ scenarios” released under Creative Commons licenses, so it’s not surprising that the book has made best use of publicly usable Lovecraftian gaming materials. (Their previous title Convicts & Cthulhu, transporting [sic.] Lovecraftian horror to early colonial Australia, has been recognized as “a historically- and culturally-significant publication by the National Library of Australia.”) The system in Apocthulhu has been almost entirely pieced together by Cthulhu Reborn’s Dean Engelhardt from existing D100 OGL material, very close to what was done for Arc Dream’s updating of the Delta Green platform. Indeed, strong hints of Delta Green recur often in the system, such as its use of personal Bonds as important pillars in a character’s losing struggle against the sanity-shattering impact of the Great Old Ones. That’s no bad thing, as Arc Dream-vintage Delta Green benefits from one of the leanest and most elegant investigative RPG systems around – one directly compatible, furthermore, with decades of BRP and d100 content for other systems, including material for Call of Cthulhu 6th and earlier editions. Apocthulhu’s mechanics are straightforward, well-tried, familiar to anyone who’s played in this genre, and occupy a relatively small proportion of the book, leaving most of its 330 pages for lavish setting detail.

Apocthulhu has inherited many of the virtues of its predecessors, yet still manages to stand apart from both Delta Green and Call of Cthulhu old and new, and be very much its own animal. For instance, the designers have put a lot of thought and work into creating a convincing resources and scavenging system for the post-apocalyptic hellscape, reminiscent if anything of the foraging mechanisms of the Fallout franchise. Potential “career” paths for survivors of the apocalypse are presented with varying levels of experience and depredation, depending on the severity of the disaster and the number of years since it befell Mankind. And rather than come up with yet another Lovecraftian bestiary, the authors have directed readers to the many that do exist, and instead whipped up eight sample apocalypses and three full scenarios, each with its own particular flavour of terror. Some of these are Mythos catastrophes involving canonical deities, or even hints dropped in some of Lovecraftian gaming’s most celebrated campaigns; others are entirely original with fresh-baked sets of very alarming horrors that more than make up for the absence of a standalone bestiary. Indeed, the game could easily be used as it stands to build a Walking Dead RPG, or to play any other non-Lovecraftian apocalyptic scenario. In a long and honourable lineage of post-apocalyptic RPGs from Gamma World onwards, Apocthulhu stands out for its grittiness and grimness, as well as for comfortably straddling the divide between Lovecraftian dread and other forms of horror.

One of its best tricks is saved, almost, for last. Apocthulhu has full d100-compatible rules for playing William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, in the longest and most detailed of its scenario settings, by Kevin Ross, which almost stands alone as a separate vehicle. Hodgson’s immensely distant sunless dreamscape, ruled by nightmare presences that besiege humanity’s last redoubt, was a formative influence on Lovecraft, but has remained very underused by RPG designers, no least because of the original novel’s turgid prose. Consequently, Apocthulhu and Kevin Ross are performing a real service to the horror RPG audience by disinterring Hodgson’s creations and framing them in such a well-proven, flexible system. Ross has said in one interview that the Night Land section is due to be expanded into a full-on standalone fork of the system, and that can’t come soon enough.

The overall standard of design and artwork for Apocthulhu is exceptionally high. Yes, there’s some style choices I may not agree with, and not every illustration is to my taste, but overall it’s at least as good-looking a book as anything you’d see from the top-line RPG majors these days. Apocthulhu is a testament to the quality and strength that modern indie game publishers can achieve in both form and content, and is likely to become many gamers’ choice for any kind of post-apocalyptic gaming, let alone Lovecraftian. You can plug it into reams of other existing games and game systems, or just ring the changes on the many options it provides by itself. The game has just gone live as a PDF on DriveThruRPG, with the print version being finalized as we speak, and you are warmly advised to snap it up. The stars couldn’t be righter.

[Top]A review of Malleus Monstrorum: Cthulhu Mythos Bestiary, by Mike Mason and Scott David Aniolowski, with Paul Fricker

Originally published in 2006, Malleus Monstrorum followed the tradition of S. Petersen’s Field Guide to Cthulhu Monsters (1988) in bringing the D&D Monster Manual and Fiend Folio approach to the Cthulhu Mythos. Chaosium has now doubled down on the great tradition of Call of Cthulhu monsters and malevolences: literally, since this is in two volumes. It’s certainly sumptuous. The slipcased two-volume hardcover edition is $89.99; the PDF is $39.99. There’s also a special leatherette hard-cover edition for all of $199.99. The cover and interior art by Loïc Muzy is literally mind-blowing, and the larger colour plates are superb.

There’s no questioning the compendiousness of the volume. You can see on the credits and copyrights page the extent to which the authors have ransacked the estates of various Cthulhu Mythos writers – Eddy C. Bertin, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Walter C. DeBill, August Derleth, Robert E. Howard, T.E.D. Klein, Henry Kuttner, Brian Lumley, Gary C. Myers, Richard F. Searight, Clark Ashton Smith, Donald Wandrei, Colin Wilson – to reframe just about all of their creations as CoC creatures. Every variation on more or less canonical creatures and divine beings is rung.

All this is a summary of the new edition’s many excellences. Those are self-evident, and any problem I have with its approach is purely personal. All the same, I do have very specific issues with it.

For one thing, there’s a certain schizophrenia in its approach. The introductory essays give extensive advice to Keepers on presenting Mythos creatures ambiguously, ringing the changes on their descriptions, ideally never referring to them directly by name unless you want to skip over them with as little time and trouble as possible. Yet you have umpteen specific, concrete articulations of the monsters in the most concrete terms, exhaustively particularized. Is that going to boost Keepers’ imaginations, or channel and tramline them?

Then there’s the more than a little gung-ho approach to Mythos deities and demigods. For some historical perspective on this, way back in an interview with Different Worlds magazine in February 1982, Sandy Petersen talked about the design process behind the original Call of Cthulhu: “At first, I tried to simply write up all the different deities as if they were normal monsters, listing SIZ, POW, and so forth for each different god, along with some brief notes about the cult, if any, of that particular being. I quickly discovered that this approach was unsuitable, since the scores I gave the various monster gods was too completely arbitrary, and the possibility of harming one in the course of play too remote for their statistics to really matter… I listed each god according to its effects when summoned, its characteristics, its worshipers, and the gifts or requirements that it demanded of those worshipers. This approach was eminently workable, and I was quite self-satisfied at its conclusion. Later on in the development of the book, Steve Perrin wanted to re-include the statistics for the deities, and thus the STR, INT, etc. of Cthulhu and the rest are now included in the game again.”

I side with Sandy Petersen on this one. Not only is the prospect of damaging a god just a little bit ridiculous in any context, it absolutely goes against the core Lovecraftian thesis that humanity is less than ants before utterly powerful and incomprehensible deities. Call of Cthulhu, needless to say, does not implement that line of thinking in its system, and Malleus Monstrorum definitely doesn’t. For instance, “Mythos deities are not (in the main) omnipotent.” That isn’t exactly the impression that one gets from Lovecraft’s descriptions of Azathoth, or even hints about Yog-Sothoth. “If hand-to-hand melee with an Old One is what you are going for, then cool – this is your game, so go for it.” Well fine, except that your game is likely to be lacking in both Lovecraftian and horror – something of a problem with a game of Lovecraftian horror. Petersen said about Call of Cthulhu in the same interview, “in the game’s present form, it plays much like an adventure mystery, such as the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark.” Nothing wrong with that, except that it misses out so much of what made Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos so unique and so genuinely terrifying.

The hobby has grown a lot since the early days of Call of Cthulhu and Petersen’s interview, with a whole raft of different approaches and styles. Despite its seven reiterations, I’m not sure that Call of Cthulhu itself has grown all the way with it. Mythos gaming has grown out and ramified in all kinds of directions from its original CoC roots, but Malleus Monstrorum doesn’t seem to have fallen far from the tree. And I wonder if this is going to leave Chaosium with an audience burnout problem, where players take up the game in a flush of adolescent enthusiasm, then drop it later because it has only limited room to grow up with them. Other RPGs, not least Delta Green, are as adult as they come, and supported by robust fan bases. For me at least, Call of Cthulhu still looks to be ploughing the (admittedly well-worn and well-tried) furrow of monster-bashing, and going monstrously monstrous on monster adversaries with a monster volume of material. Powergaming, levelling-up, minmaxing and twinking has worked well enough for D&D, after all, so why not keep pushing those same approaches For those players who game to indulge their wish-fulfilment power fantasies, Malleus Monstrorum provides whole gods that you can squash.

Of course there’s probably a bit of that kind of player in all RPGers, but there are other styles of play too, and powergaming is particularly jarring in a genre that is supposed to be about helplessness. I mean, one of the prime attractions of Call of Cthulhu was supposed to be that the more you encountered the Mythos and its creatures, the more deranged and hence helpless you became. Yet a big target HP total for a god makes it just another end level boss to bash with a bigger bashy thing. Face it, hit point stats are there so you can hit things and grind up. Hitting gods may work in D&D, but it’s hardly recommended in most other less powergaming-focused systems. If you can hit something, you can kill it: ergo, it’s only scary to a certain extent. Lovecraft’s deities and demigods suffered from no such limitation.

Also, look at the sheer crunchiness of Malleus Monstrorum. It’s all compendious stats and detail. So many RPGs now are launched as rules-lite in one form or another, including many independent Cthulhu hacks. Delta Green’s essential system rules run to just 96 pages. Fate Condensed runs to just 68 pages; The Cthulhu Hack runs to 52 pages. And One Page Cthulhu is… well. Yet, CoC’s DNA is solid BRP, just like Delta Green. It just goes to show the different ways things can go.

My feeling is that, if a large slice of the RPG community has moved away from stats-intensive, crunch-heavy systems, it’s for a good reason. But for those whose appetite for sheer crunch hasn’t been satisfied by Warhammer 40,000, we have in 7th edition Call of Cthulhu 288 pages of Investigator Handbook and 448 pages of Keeper Rulebook. And yes, 480 pages of Malleus Monstrorum.

H.P. Lovecraft himself wrote: “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” But in Malleus Monstrorum, everything is known, known: ground out in stats right down to most exhaustive, exhausting, tiresome detail. Where’s the mystery, the fear, in that? Azathoth has 500 POW, wow! That’s really Powerful! Like, that means that you actually need 50 average human magic practitioners to equal the Demon Sultan principle of all Creation and embodiment of all the forces of the entire Universe. Feel strong, you 50 dudes! And this is supposed to be the world’s Number One horror RPG.

Look at the alternative approach in Trail of Cthulhu: “we have included only two statistics for gods and titans, the additional Stability loss and Sanity loss suffered when they are encountered… Everything else is and should be entirely arbitrary and immense. Fighting a Great Old One is like fighting an artillery barrage. It doesn’t matter how many shotguns you brought.” Sure, the introduction to Malleus Monstrorum also states that: “the Cthulhu Mythos is unknowable to humanity. What scraps of information are known are drawn from rare and fragmentary texts, conversations with wizards and witches, and from life-altering exposure… What “canon” exists is loose and unreliable.” Yet that declaration seems to be working at the very least at cross purposes with the actual contents of the book. There’s an awful lot of very emphatic stats and numbers for stuff that is supposed to be so unknowable. And ultimately players are likely to be most guided by the mechanics.

Chaosium’s recent revival has produced some truly fantastic Call of Cthulhu products: Berlin – The Wicked City springs to mind; or Harlem Unbound. And there’s no denying the sheer material quality of their current reborn product range. But I do have big reservations about a large slice of their approach, and Malleus Monstrorum exemplifies those reservations. For me, it succeeds in being at once both overpowering and underwhelming. Its sheer physical quality, and quantity, masks significant conceptual shortcomings. It’s the Super Size big-box belly-filler for an audience whose tastes have grown a lot more diverse and sophisticated. Sometimes more really is less.

That said, anyone like me who enjoys a lower-key, more complex and nuanced approach to their RPGs has got to face up to one thing with Lovecraft: Is he more famous for his philosophy of pessimistic cosmicism, or for the monsters he created? I doubt he’d have anything like the name brand recognition, or the long tail of RPGs following on his legacy, if it wasn’t for tentacular Cthulhu and all the other creatures he used to embody his fears. Perhaps it’s unfair to beat Malleus Monstrorum up for an issue that starts with the author himself.

Anyway, that’s Malleus Monstrorum for you. It doesn’t incorporate much of the new narrativist developments in RPGs. It pushes the original, traditional, simulationist approach, and 1980s attitude to monsters and challenges, just about as far as it can go. So long as you’re happy with those limitations, this is as good as it can possibly get.

[Top]My new review of Mike Allen’s “Aftermath of an Industrial Accident: Stories” over on Ginger Nuts of Horror

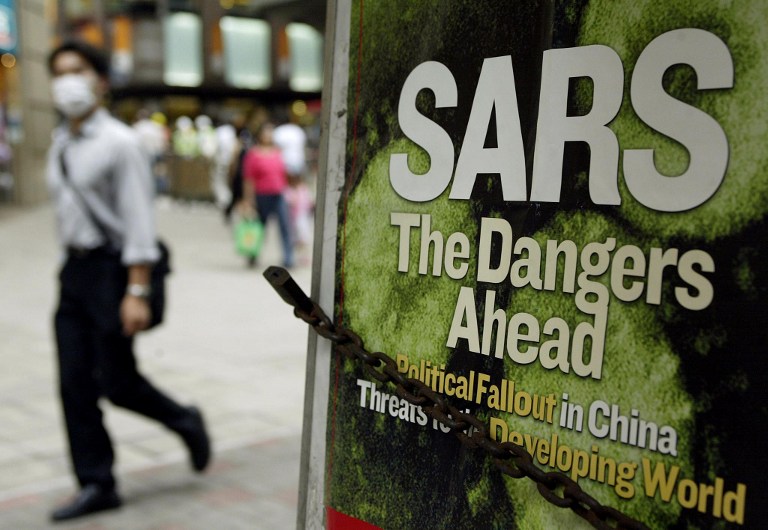

Living through SARS

The first inkling I had that the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong in March 2003 was serious was when my colleague turned up to work wearing a heavy filter mask. It wasn’t the discreet courtesy paper rectangle: it was a respirator-style cone with two great round filters on either side. She wore it the entire time as she sat at her desk, lifting it only to eat from her lunchbox.

My first reaction was anger. Here we were, working as a team, supporting each other, exposed to the same work environment, taking the same knocks, sharing the same risks and rewards in our Hong Kong PR agency, and yet here she was treating the rest of us as plague carriers. How could she break the team spirit? The only exoneration I could think of was parental pressure. Like most younger Hong Kongers, she probably lived with her family, forced to share living space by the high property prices. With typical Cantonese family sense, they doubtless had put pressure on her to keep contamination out of the home and screen out the threat from the Outside. That rationale eased my anger only a little.

I had nothing much to leave Hong Kong for in 2003, and by the time I finally realized how serious the situation was, I had lost the opportunity. SARS never quite made it into the pandemic league, since it never spread far enough. Only a score of countries were affected, and the majority of the 8,098 reported cases were in southern China. Still, it caused worldwide panic, and its prognosis was considerably grimmer than coronavirus: an average fatality rate of 9.5% of those infected, compared to at most 3.4% for COVID-19. Left unchecked, it could have killed 670,000 people in Hong Kong alone. And Hong Kong, one of the most densely populated territories anywhere at 6,659 people per square kilometer, was isolated from the rest of the world in 2003 and left to deal with SARS by itself.

Spring in Hong Kong is a humid season, and March 2003 was no exception. With its high population density and inward-looking character, Hong Kong is a claustrophobic environment at the best of times, fomenting cabin fever besides other contagious diseases. The thick low clouds hanging over the city added to the impression of a seething cauldron with the lid crammed down. Already it was effectively impossible to leave the city by any ordinary means. The World Health Organization issued an emergency travel advisory on 15 March, providing “emergency guidance for travellers and airlines.” Many countries were by that time already restricting or refusing to admit flights or passenger traffic from Hong Kong, and the WHO advisory signalled an effective global cordon sanitaire. No one could get out.

Isolation was the strongest and most immediate impression of the outbreak. The sense of imprisonment was as oppressive as the creeping dread of the disease itself. The SARs virus, of course, was invisible, and actual cases were rapidly quarantined. News reports only added to the surreal air of a nightmare you couldn’t waken from. The WHO continued “to recommend no travel restrictions to any destination,” and governments worldwide insisted that there would be no embargo of Hong Kong – while cutting flights, denying entry, and instituting a de facto embargo of ferocious comprehensiveness. Their efficiency contrasted with the Chinese authorities – hustling SARS patients out the back of hospitals when the WHO inspectors came calling, to bring the headline case numbers down. China’s venal autocracy had let the disease get out of hand in the first place, and we knew we could trust nothing that came over the border. The official lies, evasions and half-truths added to the all-pervading sense of unreality. Hong Kong resembled a ghost town, populated by phantoms. Streets were almost empty except for occasional wraithlike figures in masks. Mists and fogs worthy of any Hammer horror film clung to the peaks.

In the circumstances, we knuckled down and rode it out. We simply had no choice but to get on with stuff. We couldn’t get away, and we couldn’t be terrified 24:7. Fortitude came easy in those conditions. Offices stayed open, and work went on, though with precautions. There was never the draconian response in Singapore, where all quarantine cases were required to have a webcam connected at all times and faced random government checks to verify their presence at home, as well as to check and record their temperatures twice daily on camera if required. We went out, we drank, we partied, we went clubbing, because when we were already so much at risk, what did a little more matter? It was defiance, giving the finger to the rest of the world that had conspired, without a formal coordinated policy, to trap us there.

Besides, if we thought we had it bad, there was always someone worse off to compare with – like the residents of Amoy Gardens, the outbreak’s worst hotspot, confined within their apartment buildings behind police cordons while tenant after tenant became infected. As streetwise Hong Kongers, we naturally assumed that the cause lay in shoddy building work by the developer and poor safety standards. Sure enough, most of the contagion was traced to leaking waste pipes spraying waste water into the complex’s breathing air, but not before over 320 people had been infected. In April, the residents were transferred to quarantine camps in remote districts.

Then there were the doctors, nurses and healthcare workers, always the frontline casualties in any battle against disease. You can still see in Hong Kong Park above the harbour a poignant memorial to eight doctors, nurses, and ward attendants who died from the disease while fighting its spread. They were the community’s local heroes, in contrast to the leadership, disdained at the best of times.

Quarantine, like war, is months of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror. Add to that frustration. Much of our pushback against the official guidance on self-seclusion in Hong Kong during SARS was pure frustration, rather than deliberately flouting authority. In any event, we had plenty of time to build up a hell of a head of frustration. On 23 May, the WHO lifted its Tourism Warning for Hong Kong and Guangdong, and the moment the informal blockade was lifted, I was on my way to Singapore.

That was our limited little plague over. Hong Kong’s final toll was 1,755 confirmed cases and 299 deaths from SARS. Samples of the SARS virus are still among the few classified as Biosafety level 4 organisms by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), alongside the Ebola and Marburg viruses and ricin.

What were my takeaways from SARS for the coronavirus pandemic? National sovereignty is a great way of ducking your wider responsibilities: that was one. The Communist Party of China can never be trusted to put the lives of its own citizens or the wider global community before its own monopoly on power: that was another. But if I learned any personal lesson from the experience, it was the value of patience. Any courage we showed under SARS was obligatory. We had no choice. We weren’t going anywhere. We had no agency, no power to alleviate the situation. We just had to get through it.

In a society powered by instant gratification, patience and forbearance are habits that take some reacquiring. We’re told constantly that our slightest twinge is worthy of attention, that we’re entitled to have our most insignificant discomforts and discontents pandered to. We confuse our entitlements with our rights. We feel entitled to have our fears pandered to instantly, as with our desires. SARS at least put that in perspective. It helped immunize me against fear. Now at least I’ve been through it and come out the other side. So, hopefully, will most of us

[Top]A review of The Foulness Island Vanishings, by Glynn Owen Barrass & Friends

Stygian Fox is producing original Call of Cthulhu 7th edn. scenarios at a rate of knots nowadays, and this Second World War Era volume by the illustrious (and industrious) Glynn Owen Barrass is a shining example. The Foulness Island Vanishings: A Corrupting Infiltration In A Time Of War, in full, is, unsuprisingly, set on the real-life Foulness Island off the south-eastern coast of England in 1941, and mingles wartime paranoia with far more malign influences. The whole scenario breathes a very strong sense of time and place, like something out of a Second World War propaganda film – perhaps Went the Day Well? with its bizarre breakdown of English village life – and contains a lot of useful setting information that could be applied elsewhere. And although the scenario is fully written out for CoC 7th edn., it doesn’t look hard to tweak for Achtung! Cthulhu or other appropriate systems.

As for the scenario itself, its 84 excellently illustrated colour pages make full use of the island’s diverse locations and inhabitants in unveiling the story of a very strange infestation indeed. The maps, handouts, and house plans match the high visual quality of the rest of the book. The horror tropes are at times pretty unpleasant, and the scenario carries a Mature Gamers rating for a reason. There is certainly plenty of human evil on display, redolent of wartime atrocities, but the Unnatural brings in its own level of veriest awfulness to boot. By the end, Investigators certainly won’t feel that they’ve had a drab wartime ration of adventure and horror.

If Stygian Fox continues its present tear of high-quality Cthulhu Mythos material, I think we’ll all be the better for it. Production values are superb, and easily match the quality of the core 7th edition materials. And Stygian Fox’s choice of subjects seems to be sweeping an attractively wide field. For now, take a mental time-out from sequestration to enjoy another time and place of isolation and menace, and experience the foulness of Foulness.

[Top]A review of Dead Light and Other Dark Turns, by Alan Bligh, Matt Sanderson, Lynne Hardy and Mike Mason

If you’re driving in backwoods America, don’t stop for anything. That’s the lesson of Dead Light and Other Dark Turns, Chaosium’s latest scenario book for the Call of Cthulhu 7th edition rules. Alan Bligh and Mike Mason’s Dead Light should already be familiar to many of Call of Cthulhu aficionados as it was first published in 2014. The original edition appeared in dual-statted form to allow players to have a taste of the new 7th edition rules in progress. This new version fine-tunes and fully reskins the scenario for 7th edition, while also updating the materials to the current Chaosium style and level of quality with brand new artwork. It also includes a brand new scenario in the shape of Matthew Sanderson’s Saturnine Chalice. The old edition was just 32 pages: the new one is 90 pages, including extensive handouts. The scenarios are written for classic era 1920s CoC, and unfold in typical Lovecraft country, but could be rejigged for other periods and locations with relatively little effort.

Back at its first release, Dead Light was hailed by at least one reviewer as: “the best title released by Chaosium in years.” Since then, Chaosium has arguably upped its game and has been churning out high quality work in spades, but Dead Light especially has an original and unusual nemesis whose characteristics help add a nasty tinge of moral squalor to the cosmic horror. Saturnine Chalice may seem a little more familiar in its choice of threats, at least on the surface, but the clue trail is (optionally) puzzle-based, which makes for a different slant on typical gameplay, and the unfolding mystery is rich in head-fuckery. There are also shorter seeds for road trip encounters and adventures at the end of the book.

This is definitely a worthwhile addition to the roster of 7th edition CoC scenarios available, especially for shorter more stand-alone adventures. At the inconsequential price that Chaosium is asking for it, it’s a steal even for owners of the original Dead Light. Recommended for Call of Cthulhu players old and new.

[Top]A review of New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, 2nd edition, by Tom Lynch, Christopher Smith Adair, Oscar Rios, Kevin Ross, Keith “Doc” Herber and Seth Skorkowsky

As the blurb for Stygian Fox’s Kickstarter explains, “Miskatonic River Press released New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley to great acclaim and it quickly became a favourite among Call of Cthulhu Keepers.” This is essentially a resurrection of a much-loved scenario book, originally published in 2009 as a follow-up to Chaosium’s 1991 Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, which also gives an opportunity to see how RPG publishing has moved on since Chaosium’s 1991 effort and the original New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley. Tom Lynch’s personal dedication to the book is a heartfelt reminiscence of Keith Herber, CEO of Miskatonic River Press, lamenting the sad demise of the publisher and the publishing house. Keith Herber was a powerhouse of scenario-writing in the early days of Call of Cthulhu, producing almost 50 scenarios for Chaosium in the 1980s and early 1990s, and it’s not surprising that his tragically short re-emergence as founder of Miskatonic River Press in 2003 has left a lasting impression on the modern Lovecraftian gaming scene. The whole exercise obviously has had a lot of love lavished on it, and Call of Cthulhu players are the fortunate beneficiaries.

The original six scenarios in New Tales have stood the test of time and are reprinted in full, freshly rejacketed and statted up, not only to run on Call of Cthulhu 7th edition rules, but also to bring their presentation up to the kind of standard we’ve come to expect from the newly reborn Chaosium and their associated projects. There’s an additional new scenario from Seth Skorkowsky, “A Mother’s Love,” extending the book’s coverage to Innsmouth with an appropriately twisted tale of miscegenation and mayhem. I’d still be happy to play these scenarios through with earlier Call of Cthulhu rules, or indeed with Trail of Cthulhu or other systems, because they focus so much on drama and story rather than pure game mechanics. There are plenty of human protagonists and antagonists with their own mundane agendas that can trip up the players as effectively as any scheming cultists. The unnatural horrors that do appear are a refreshing mixture of new takes on Cthulhu Mythos staples and original creations, and should be enough to stimulate the most jaded Call of Cthulhu grognard.

The real surprise for anyone familiar with the black-and-white layout and fairly limited art of the original is the visual presentation of the 2nd edition. Stygian Fox has done a frankly incredible job on the production values. The maps of Arkham, Dunwich and other favourite Lovecraftian locales are the best I’ve seen, even when set against the superb cartography in the latest Chaosium products, and the handouts and period prop pieces are equally luscious. Stygian Fox was working off a Kickstarter that closed at roughly 400% of its target, and the money has been well spent. There are even terrific multi-page handouts for pre-rolled characters. “The original is black and white and 130 pages,” Stygian Fox noted. They managed to expand the final publication to 240 full-colour pages.

Would I recommend this book to anyone who had the original edition? In a heartbeat. It’s not just the extra material and the restatting of the stories to Call of Cthulhu 7th edition. It’s the superlative production, which is bound to be usable in other campaigns. Indeed, if you want to run a 1920s campaign in canonical Lovecraft Country, I’d advocate this book as a go-to for mapping out all the core locations – Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, Kingsport, and environs – in immaculate style. The full-colour double-page panorama of Arkham, for instance, captures that Mythos-ical city exactly as I’ve always imagined it. Furthermore, Chaosium still hasn’t released updated 7th editions of many of its own classic Lovecraft Country scenario books – such as Keith Herber’s original H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham and H.P. Lovecraft’s Dunwich. That puts New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley, 2nd edition to the fore as the Number One CoC 7th edition canonical Lovecraft Country supplement – a position it full deserves to occupy. It’s a testament to the current health and vigour of Call of Cthulhu gaming, and a worthy tribute to its progenitor.

A review of Petals and Violins: Fifteen Unsettling Tales, by D.P. Watt

Introduction by Peter Holman, Afterword by Helen Marshall

D.P. Watt is already a Shirley Jackson Award nominee for his 2016 collection from Undertow Publications, almost insentient, almost divine, so he’s well established among readers of weird and dark fiction. In fact, he’s written 8 books by my count, including this one. Despite the fact that Petals and Violins comes heavily flagged as a chunk of the Weird Renaissance, with an afterword by Helen Marshall, there are plenty of stories here that would appeal to the most recherché traditional ghost story enthusiast. D.P. Watt is not especially a representative of any particular school or trend, and very much his own animal. The author has said in one past interview that “The process of composition changes with each story, and I have no particular allegiance to any movement, nor indeed anything as well-formed as a technique that I can deploy. My writing seems now to be more driven by scenes that emerge as I am working.” (Bibliophagus, 2015) That’s certainly what comes across here, and it’s a process that’s to be welcomed.

The opening story, “Blood and Smoke, Vinegar and Ashes,” for instance, is a tale of folk alchemy in rural Poland, and the remarkable results achievable by the quoted ingredients and others; M.R. James could have well produced his own version of the theme. “Mizpah” and “The Magician, or, Crab Lines” also have that flavour of folk horror, in narratives closer to Daphne du Maurier’s The House on the Strand. (Indeed, du Maurier’s blend of psychological tension, the paranormal and supernatural, and a very strong English sense of place and the past, finds substantial echoes in D.P. Watts’s work.) The most ambitious, and distinctive, story in the book is “Conflagration: Immoral Vignettes,” a slideshow of historical, tragical tableaux featuring writers from 1895 to the present, from August Strindberg to Tadeusz Kantor. D.P. Watt has certainly experimented plenty with form in the past, notably in his novella The Ten Dictates of Alfred Tesseller, and this is the most stylistically extreme story in the collection – and, in my opinion, one of the best. I could go on and on about the value of using history and aesthetics as imaginative resources, instead of typical horror set-dressing or weird psychobabble, but it definitely works. Any more traditional reader who balks at this approach is advised to stick with it. “The Pedagogue, or, They Muttered” is more in the Lovecraftian vein of pedantic academia touching cosmic horror, while “A Species of the Dead” is closer to psychological horror, where the disturbance of the natural order is purely social and mental.

It goes without saying that a writer this experienced is fully on top of his craft, and can turn a phrase or string a narrative with hooks. Weird or dark fiction, ghost stories, horror or surrealism, whatever you call it, this loose cluster of genres is in rude good health in Britain right now, and D.P. Watt is a tremendously accomplished practitioner. Petals and Violins is a box of dark gems.