Living through SARS

The first inkling I had that the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong in March 2003 was serious was when my colleague turned up to work wearing a heavy filter mask. It wasn’t the discreet courtesy paper rectangle: it was a respirator-style cone with two great round filters on either side. She wore it the entire time as she sat at her desk, lifting it only to eat from her lunchbox.

My first reaction was anger. Here we were, working as a team, supporting each other, exposed to the same work environment, taking the same knocks, sharing the same risks and rewards in our Hong Kong PR agency, and yet here she was treating the rest of us as plague carriers. How could she break the team spirit? The only exoneration I could think of was parental pressure. Like most younger Hong Kongers, she probably lived with her family, forced to share living space by the high property prices. With typical Cantonese family sense, they doubtless had put pressure on her to keep contamination out of the home and screen out the threat from the Outside. That rationale eased my anger only a little.

I had nothing much to leave Hong Kong for in 2003, and by the time I finally realized how serious the situation was, I had lost the opportunity. SARS never quite made it into the pandemic league, since it never spread far enough. Only a score of countries were affected, and the majority of the 8,098 reported cases were in southern China. Still, it caused worldwide panic, and its prognosis was considerably grimmer than coronavirus: an average fatality rate of 9.5% of those infected, compared to at most 3.4% for COVID-19. Left unchecked, it could have killed 670,000 people in Hong Kong alone. And Hong Kong, one of the most densely populated territories anywhere at 6,659 people per square kilometer, was isolated from the rest of the world in 2003 and left to deal with SARS by itself.

Spring in Hong Kong is a humid season, and March 2003 was no exception. With its high population density and inward-looking character, Hong Kong is a claustrophobic environment at the best of times, fomenting cabin fever besides other contagious diseases. The thick low clouds hanging over the city added to the impression of a seething cauldron with the lid crammed down. Already it was effectively impossible to leave the city by any ordinary means. The World Health Organization issued an emergency travel advisory on 15 March, providing “emergency guidance for travellers and airlines.” Many countries were by that time already restricting or refusing to admit flights or passenger traffic from Hong Kong, and the WHO advisory signalled an effective global cordon sanitaire. No one could get out.

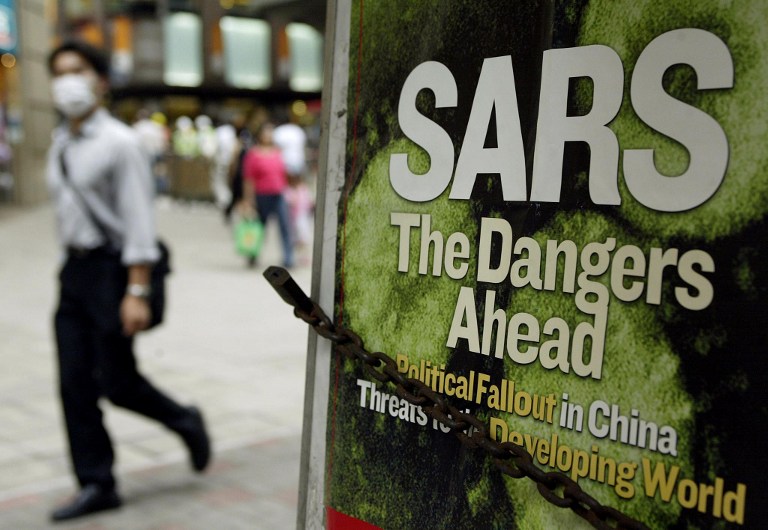

Isolation was the strongest and most immediate impression of the outbreak. The sense of imprisonment was as oppressive as the creeping dread of the disease itself. The SARs virus, of course, was invisible, and actual cases were rapidly quarantined. News reports only added to the surreal air of a nightmare you couldn’t waken from. The WHO continued “to recommend no travel restrictions to any destination,” and governments worldwide insisted that there would be no embargo of Hong Kong – while cutting flights, denying entry, and instituting a de facto embargo of ferocious comprehensiveness. Their efficiency contrasted with the Chinese authorities – hustling SARS patients out the back of hospitals when the WHO inspectors came calling, to bring the headline case numbers down. China’s venal autocracy had let the disease get out of hand in the first place, and we knew we could trust nothing that came over the border. The official lies, evasions and half-truths added to the all-pervading sense of unreality. Hong Kong resembled a ghost town, populated by phantoms. Streets were almost empty except for occasional wraithlike figures in masks. Mists and fogs worthy of any Hammer horror film clung to the peaks.

In the circumstances, we knuckled down and rode it out. We simply had no choice but to get on with stuff. We couldn’t get away, and we couldn’t be terrified 24:7. Fortitude came easy in those conditions. Offices stayed open, and work went on, though with precautions. There was never the draconian response in Singapore, where all quarantine cases were required to have a webcam connected at all times and faced random government checks to verify their presence at home, as well as to check and record their temperatures twice daily on camera if required. We went out, we drank, we partied, we went clubbing, because when we were already so much at risk, what did a little more matter? It was defiance, giving the finger to the rest of the world that had conspired, without a formal coordinated policy, to trap us there.

Besides, if we thought we had it bad, there was always someone worse off to compare with – like the residents of Amoy Gardens, the outbreak’s worst hotspot, confined within their apartment buildings behind police cordons while tenant after tenant became infected. As streetwise Hong Kongers, we naturally assumed that the cause lay in shoddy building work by the developer and poor safety standards. Sure enough, most of the contagion was traced to leaking waste pipes spraying waste water into the complex’s breathing air, but not before over 320 people had been infected. In April, the residents were transferred to quarantine camps in remote districts.

Then there were the doctors, nurses and healthcare workers, always the frontline casualties in any battle against disease. You can still see in Hong Kong Park above the harbour a poignant memorial to eight doctors, nurses, and ward attendants who died from the disease while fighting its spread. They were the community’s local heroes, in contrast to the leadership, disdained at the best of times.

Quarantine, like war, is months of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror. Add to that frustration. Much of our pushback against the official guidance on self-seclusion in Hong Kong during SARS was pure frustration, rather than deliberately flouting authority. In any event, we had plenty of time to build up a hell of a head of frustration. On 23 May, the WHO lifted its Tourism Warning for Hong Kong and Guangdong, and the moment the informal blockade was lifted, I was on my way to Singapore.

That was our limited little plague over. Hong Kong’s final toll was 1,755 confirmed cases and 299 deaths from SARS. Samples of the SARS virus are still among the few classified as Biosafety level 4 organisms by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), alongside the Ebola and Marburg viruses and ricin.

What were my takeaways from SARS for the coronavirus pandemic? National sovereignty is a great way of ducking your wider responsibilities: that was one. The Communist Party of China can never be trusted to put the lives of its own citizens or the wider global community before its own monopoly on power: that was another. But if I learned any personal lesson from the experience, it was the value of patience. Any courage we showed under SARS was obligatory. We had no choice. We weren’t going anywhere. We had no agency, no power to alleviate the situation. We just had to get through it.

In a society powered by instant gratification, patience and forbearance are habits that take some reacquiring. We’re told constantly that our slightest twinge is worthy of attention, that we’re entitled to have our most insignificant discomforts and discontents pandered to. We confuse our entitlements with our rights. We feel entitled to have our fears pandered to instantly, as with our desires. SARS at least put that in perspective. It helped immunize me against fear. Now at least I’ve been through it and come out the other side. So, hopefully, will most of us