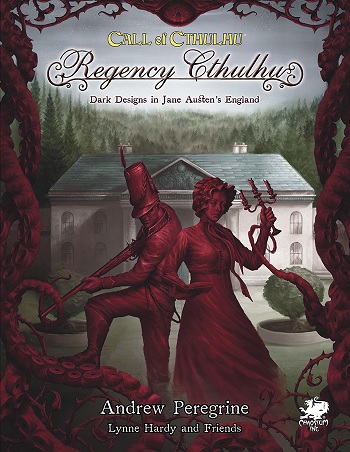

A review of Regency Cthulhu: Dark Designs in Jane Austen’s England

by Andrew Peregrine, Lynne Hardy and Friends

226 pages

Published by Chaosium, 2022

Your mileage may vary, but I’ve found that the more detail, meat and juice there is in a historical sourcebook for an RPG, the more I get out of it, and the more stimulating and just plain useful it is. I mean, there’s usually so much unexpected, fascinating, and crazy stuff going on in any one timeframe that you only need shake the box a little to have fabulous scenario seeds pouring out. That’s got to be worth the cost of admission, right?

So I was hoping for a lot from Regency Cthulhu. Did I get it? Well, in its 226 pages, the Introduction is basically all the generally explanatory material on the Regency era – and it’s only 16 pages long. Actually, half of that is a Regency timeline – so in fact, for this introduction to an unfamiliar, incredibly diverse and dramatic historical setting, we’re looking at a grand total of eight pages, with a lot of half-page illustrations to cut down that text even more. That’s close to the length of the setting introductions for each individual chapter of Masks of Nyarlathotep.

As the Introduction states, the book really focuses on the Regency as strictly drawn – the “reign” of the Prince Regent, between 1811 and 1820 – pretty much Jane Austen’s entire mature publishing career. Yet even within that period, there is so much fascinating and supremely gameable material that it leaves out. For instance, Byron, Percy Shelley, Mary Shelley, and Polidori had their great horror story contest on the banks of Lake Geneva in 1816, which produced Frankenstein in 1818. There’s Beau Brummell and the political shenanigans of the Regency itself. There’s the first steam engines. There’s the Peterloo Massacre. And then there’s the culmination of the Napoleonic Wars. Yes, those Napoleonic Wars – the Retreat from Moscow, the Hundred Days, Waterloo, and all that.

There are great cultural currents in the period that flow right into horror and horror gaming. I’ve already touched on a couple of really massive peaks that helped shape the entire horror genre. They’re often classed as the second generation of Gothic literature – and Jane Austen herself cut her teeth (pretty literally) on satirizing the first generation. Austen’s decorous, refined culture existed in dynamic counterpoise with the dramatic, hysteric excesses of Romanticism – John Martin’s apocalyptic canvases, William Beckford’s erection of his bizarre follies at Fonthill Abbey and Landsdown Tower, Walter Scott’s rediscovery of the Scottish Crown Jewels, John Polidori’s publication of his vampire tale The Vampyre, and so on, and on, and on. All of which features hardly at all in this book.

In Regency Cthulhu, pages 8 to 42 are devoted to the introduction, a general outline, and the period and customization details needed to create a Regency investigator. Some six pages are devoted to equipment and price tables, and other period details. The production values are high, yes – in the same current generic Chaosium house style, which is pretty solidly good (although perhaps a touch lacking in the kind of neo-classical feel that could have fleshed out the sense – and sensibility – of the period). And the rest is almost entirely devoted to three interconnected scenarios and their supporting handouts and pregens. I understand from podcasts that the book grew out of Andrew Peregrine’s own independently developed Regency scenarios, rather than the scenarios being commissioned to match the system. And yes, they’re three very good and playable scenarios, rich with the flavour of the period, and providing plenty of setting and character detail that can be worked into a campaign. But that is exactly how much this book gives you to create your own Regency setting and Regency investigators – the bare bones. The new Reputation system is a terrific addition to the Call of Cthulhu repertoire, and perfectly tailored to Regency society, while potentially being adaptable for Gaslight and other eras too, but it’s a new mechanic, rather than a presentation of source material for a sourcebook.

I sadly feel the lack in Regency Cthulhu of the phenomenal density of historical and cultural detail that went into Lynne Hardy’s brilliant The Children of Fear. It feels like an RPG version of Bridgerton – a costume pastiche whose knowledge of the era goes no deeper than its frocks. And I know that’s not representative of the authors’ knowledge or love of the period, but it’s all that gets through here. It’s kind of indicative in my view that the handouts include a one-page summary of the Regency era – presumably for players who can’t even be bothered to go through the fairly basic introduction to the period in the book. There is so, so much great gaming material and potential from the period that’s hardly even referenced in a one-liner. Fine, you can’t cover everything – but Chaosium has covered loads more, in supplement after supplement, in its recent production lineup. The Children of Fear, in contrast, is about twice as long, at 416 pages, and infinitely deeper in detail, even though its setting is far more alien. Or look at David Larkins’s Berlin: The Wicked City, with its dazzling and decadent recreation of the spirit and fleshy details of the Weimar period. And couldn’t there have been more genuinely period illustrations in the book, instead of just more Chaosium house style art, since it covers an epoch of fabulous imagery, from Gillray’s satires to Blake’s phantasmagoria? How about a map of Bath, or Regency London? Or some period pamphlets? I mean, call me an intellectual snob if you like, but I haven’t found any reason to complain about lack of detail in any of Chaosium’s recent sourcebooks and scenarios, and I’ve read and/or reviewed just about all of them. And those incorporate a great deal of input from some of the same writers. So if those standards were applied there, couldn’t they have been applied here? I know that the authors are huge fans of the period, and it’s a colossal shame that their enthusiasm couldn’t have been reflected in more material that is – well, source material. And yes, it’s true that some key modern properties about the period, such as Bernard Cornwell’s Richard Sharpe series, or Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey–Maturin cycle, are still in copyright, but Frederick Marryat’s Mr Midshipman Easy isn’t. Nor is Nightmare Abbey. Nor is Vanity Fair. Or Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley. Or Billy Budd. Or Shelley’s Zastrozzi.

I understand that other follow-up publications to Regency Cthulhu may be in the offing, and I’d really love to see a Napoleonic or Romantic CoC sourcebook from Chaosium to flesh out what this one has missed – because IMHO it does stand in need of them. (And no, I am not pitching for work myself here – just commenting.) Rather than a sourcebook, it reads like three extended scenarios with a fairly abbreviated historical background. Even the appendix updating the scenario setting of Tarryford to 1913 is longer than the consecutive space given to the source material; just turning those 9-10 pages over to real Regency content could have made this a hugely more fruitful and faithful resource for Keepers.

This is the first Chaosium product in ages that I wouldn’t rate as an instant classic – which is kind of praising with faint damnation, maybe, but there you go. I’m reminded painfully of the title of another great English novel that followed a bit later – Great Expectations. That’s what mine were. I realize Chaosium can’t roll a critical hit every time, but it’s a shame that this one had to be the one they missed on. Ah well, back to Reign of Terror.